by TCW | Apr 1, 2019 | Book review

After the double-crosses and triple crosses and general chaos of the second of Jemahl Evans’ Blandford Candy books, Of Blood Exhausted is a relief. Even I could follow (most of) the plot. Evil foreigners are planning to assassinate Karl Ludwig, the Elector Palatine, who is visiting London in the hope (not totally absurd) that he might be offered the throne if Charles is deposed. His death, Evans tells us in an impressively succinct summary, “could drive a wedge between the Protestant states, and perhaps even tip the Dutch provinces into active war against the English Parliament.” Candy’s mission is to protect the Elector.

A French agent is also on a mission to protect Karl Ludwig, for reasons that are explained somewhat less succinctly. You can hardly blame Evans for that – it’s related to a whole series of alliances in Europe and he does well to explain it all. It is, though, an example of one of the many instances where Evans the writer loses out to Evans the historian, which is a shame, because Evans the writer can tell a very good tale. Anyway, the history lesson out of the way, we can concentrate on the fact that the Frenchman is d’Artagnan. Yes, that d’Artagnan. It turns out that the d’Artagnan of The Three Musketeers was a real person and that he did indeed spend time in England during the Civil War, though his adventures here are wholly fictional.

D’Artagnan is very French and witty. Sadly his wit suffers from the fact that Evans insists on translating every single word he says. Evans is a huge fan of footnotes (there are 76 in this book) but the one time footnotes would be more than justified he insists on putting everything in parentheses in the text. Even with this handicap, d’Artagnan is still much more witty than poor Blandford Candy who is regularly and amusingly shown up, but the two of them work together to track down the assassin who is duly killed. The Elector’s life is saved, d’Artagnan returns to France and Blandford Candy can go back to womanising without the Frenchman’s insufferable competition.

This relatively straightforward plot allows for an enormous amount of detail about the Civil War – the battles, and the politics that underlay them. Evans knows his period and makes as much sense of the history as anybody else I’ve read. The Civil War was messy and complicated and the Blandford Candy books are as good a way to get to know it as any. There’s an enormous amount of detail of daily life, lovingly researched (see those 76 footnotes) and brought vividly to life. It’s not as easy to read as, say, Deborah Swift, but then her adventures in Restoration England are painted on a much smaller canvas. She even presents Pepys as husband and man-about-town first and as an important civil servant at the Admiralty second. Evans is dealing with high policy, his book peopled with key political figures of the period who spend much of their time talking about the big policy issues of the day.

By the end of the story, the war is over. Charles is still alive, but his armies no longer threaten Parliament. That would mark a natural finish to the book, but Evans obviously has more plans for Blandford Candy who is about to build a new life for himself in America. Sadly his adventures between the natural end of the book and finally boarding the ship that will cross the Atlantic reminded me of the coda to Lord of the Rings as we wait what seems like forever for that ship to arrive and our hero to finally embark for the west. It’s a shame, because the last impressions the book leaves you with are in no way a fair reflection of the excellent quality of the rest of it.

by TCW | Mar 26, 2019 | Book review

Exactly a year ago I reviewed The Darkness by Ragner Jonasson. The publishers have very kindly sent me a copy of his next book, The Island, which will be published next week.

The main character is Hulda Gunnarson, who [SPOILER IF YOU HAVEN’T READ THE DARKNESS] died in the first book. It’s a bit disconcerting and it took me a while to appreciate that I was reading a prequel. I appreciated the chance to learn more about Hulda, though, as I had found her a fascinating character in The Darkness.

In many ways The Island is more a story about Hulda than it is a detective story. The ‘whodunnit’ element is quite thin, though it does hold together as a mystery and the characters are interesting enough to make the read feel worthwhile. It’s the little details of characterisation that I love about Jonasson’s writing. Here he is writing about a couple who are such minor characters that they never appear in the story again, but this catches exactly the mood of so many people who are just beginning to realise that their youth is behind them.

In the end, they set off home a little earlier than planned, just after eleven. The three-course dinner was over by then, and, to be honest, it had been a bit underwhelming. The main course, which was lamb, had been bland at best and, after dinner, people had piled on to the crowded dance floor. To begin with, the DJ had played popular oldies, but then he moved on to more recent chart hits, which weren’t really the couple’s sort of thing, although they still liked to think of themselves as young. After all, they weren’t middle-aged yet.

The eye for character and telling details of daily life is a joy, but it can get in the way of the story, making for a somewhat “bitty” narrative. A trip Hulda makes to the USA in an attempt to track down her father, in particular, is completely detached from the rest of the story. It’s almost as if Jonasson really wants to write a literary novel about contemporary life in Iceland but has been forced by commercial pressure to write a detective story. The result is almost two separate books that don’t quite make a cohesive whole.

The Island is more mainstream than the full-on Scandi-noir of The Darkness. It centres on the investigation of a single murder in the Icelandic version of a classic country house mystery: four people spend a weekend on an isolated island and one is killed. The murderer has to be one of the remaining three. After the Grand Guignol of The Darkness I was amused by the constant reassurance that murder is extremely unusual in Iceland. Perhaps after The Darkness increased Iceland’s murder rate by several hundred percent the Reykjavik tourist board pressured Jonasson to ease off this time.

Flawed as it is, I enjoyed reading The Island. Jonasson has an easy style that kept me up late reading on and I enjoyed learning more about Hulda. It isn’t one for hard-core fans of detective fiction, but it’s definitely worth a look if you want character-driven stories in unfamiliar settings.

by TCW | Mar 19, 2019 | Book review

My publishers, Endeavour Media, are running a promotion on Sally Spencer’s books. I started reading her because of her Inspector Blackstone mystery series set in Victorian London, but she also writes contemporary crime fiction. As part of the promotion, Endeavour are giving away one of her contemporary thrillers, The Vital Chain, so this seemed a good time to post a review of one of her other contemporary stories that I wrote a couple of years back.

Spencer is British and most of the stories I’ve read are set in England (as is The Vital Chain) but Violation is firmly established somewhere in the American rustbelt. Our hero (and first person narrator), Mike Kaleta, is an East Coast liberal who has moved to this tiny town where his wife’s father is the mayor. His marriage, though, has collapsed and he is now a liberal fish out of water in a police department staffed largely by thugs and headed up by an idiot. The only exception is Caroline Williams. Rule-bound and officious as she is, the only woman on the detective force is, inevitably, attractive.

Kaleta and Williams are set to work together to solve a series of paedophile sexual assaults. I must admit to finding the detail of some of these assaults quite unpleasant and I’m not sure how suitable this kind of crime is for what is, essentially, a lightweight novel. Still, the seriousness of the crime does provide some grist to what might otherwise be an overly predictable tale of corrupt officials, dirty cops and a heroic committed crime busting team. At first I thought the story, which pulls up every cliché of hard-boiled crime fiction, far too predictable. (Kaleta’s romance with Williams is inevitable from the moment that he tells us how much he hates her whilst trying to guess what her legs look like under her uniform.) I suspect Spencer would say that she was aiming for homage rather than rip-off and eventually I decided that she does pull this off. She’s not Raymond Chandler but her style has wit and a hard-boiled humour. Turning down a courtesy blow-job from the town whore, Kaleta says, “I hate to look a gift-mouth in the horse.” In a story-so-far aside he tells the reader, “Only a couple of days ago I forced two cops off a cliff, and now I’ve sunk to lying. By tomorrow I’ll probably be stealing from the cookie jar.” More importantly, the prose bowls along, carrying the reader with it. As the plot develops it becomes a little less predictable than you might have expected, although anyone paying attention will have spotted the evil villain more or less when they first appear with “Evil Villain” stamped across their forehead. Still, the twist at the end is worth waiting for and I found that, for all my reservations, I had genuinely enjoyed the read. I’ll probably read another (for a sequel is as predictable as Kaleta’s enthusiasm for bourbon).

by TCW | Feb 19, 2019 | Book review

It’s Iceland in 1828 and Agnes Megnusdottir has been sentenced to death for murder. At the time, Iceland was ruled by Denmark, so the sentence has to be confirmed by the King in Copenhagen. As there is no prison in Iceland it is decided that, while she waits for the King’s word, Agnes should live in one of the isolated farms in the north of the island, working as a servant for the family there.

This is the background to Hannah Kent’s extraordinary novel, Burial Rites.

Nothing much happens. Agnes turns out not to be the monster people expected. She discovers that some people treat her with unexpected kindness while others don’t. The long winter turns to summer and then the days get shorter again.

As Agnes learns to trust other people around her, we learn more of the murder and how Agnes got caught up with it, but while the people she is living alongside grow increasingly sympathetic, the machinery of justice grinds on. An axe is bought and there is a bureaucratic exchange of notes between Iceland and Copenhagen as to who should pay for it. Legal processes are completed. The execution day arrives.

That’s all. That such a slight storyline becomes such a gripping read is down to the smoothness of Hannah Kent’s writing, her ability to draw us into the characters so that we not only know them but care about them too, and the detail of everyday life on an Icelandic smallholding 200 years ago.

When I was reading, I found myself wondering how much of the story was true. It was only when I had finished that I read the acknowledgements and discovered just how much research had gone into it. The basic story, it turns out, is quite possibly true, although to this day there are differing views as to Agnes’s culpability. More importantly, Kent has done an enormous amount of research into life in this remote place so long ago. Historical novelists are always caught between the danger of not providing a textured background on the one hand and of overwhelming their readers with irrelevant detail on the other. Authors are always told that they should research in depth but wear that knowledge lightly when they write. Kent is a rare and splendid example of somebody who gets it just right. When I was reading I felt that the historical details didn’t matter. Kent painted a picture of people living a harsh life, in almost constant darkness for several months of the year, in farms so isolated that you could die just walking to a neighbour. The images are so vivid that you see that harsh landscape on the shores of a grey sea that might as well be the edge of the world. It was only when I finished that I realised that the tiny details – the herbs they used, the way they slaughtered the sheep, the fuel they burned (dried dung for heat, peat to bank the fire at night) – were what made the whole thing so real. And because we see the scene so clearly, so we come to understand the people shaped by this harsh landscape and we come to understand something of their hopes and fears and, to an extent to share them.

This is an astonishing book. Do read it.

by TCW | Feb 12, 2019 | Book review

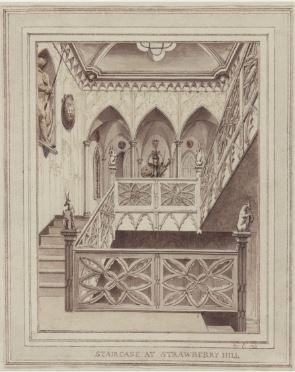

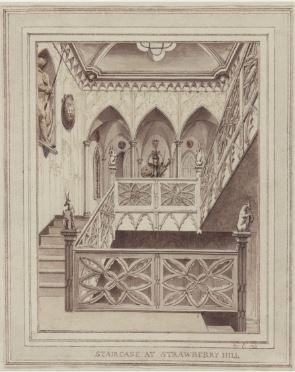

My visit to Strawberry Hill made me re-read The Castle of Otranto, Walpole’s novel which is supposed to have started a fashion for Gothic novels that has never really gone away.

Published in 1764, it’s a curiosity piece rather than a book you would read for its literary merit. Seriously, it doesn’t have any literary merit but it does have a giant ghost that can smash down castle walls with his fists; an evil usurper; not one, but two, beautiful princesses; a peasant boy who turns out to be a prince (identifiable by a birthmark, obviously) … Honestly, if Walpole missed out a single Gothic trope, it wasn’t for lack of trying. Despite the packed plot line, it’s quite a short book and if you want to read the great-grandfather of all Gothic novels it’s an hour or two not entirely wasted.

The Castle of Otranto from an illustration in the original book. Rather larger than Strawberry Hill

The Castle of Otranto from an illustration in the original book. Rather larger than Strawberry Hill

For me, part of the fun came from the fact that the architecture of Strawberry Hill House is supposed to have inspired the book. (Walpole called Strawberry Hill “my own little Otranto”.) Sadly, Strawberry Hill lacks an underground passage to a nearby church although Walpole’s neighbour, Pope, did build an underground passage from his house to the famous grotto and this might have inspired Walpole’s imagination. Much of the rest of the story’s setting also has only tenuous links with Strawberry Hill House, but there is indeed a staircase with some assorted pieces of armour. Originally there was a lot more than we see today. Walpole claimed, rather improbably, that the armour had all been taken by one of his ancestors in the Holy Wars (though the descriptions of Indian weaponry make this unlikely). In any case, the armour inspired the story of the giant armoured knight who brings the Castle of Otranto to its doom and which we first meet in one of the rooms leading off the “armoury” gallery. Two servants bring the news to Manfred, the usurper Prince of Otranto.

“My Lord,” said Jaquez, “when Diego and I came into the gallery … We found nobody. … When we came to the door of the great chamber … We found it shut.” “And could not you open it?” said Manfred. “Oh yes, my lord; would to heaven we had not,” replied he. … “Trifle not,” said Manfred, shuddering, “but tell me what you saw in the great chamber, on opening the door.”… “It is a giant, I believe; he is all clad in armour, for I saw his foot and part of his leg …”

Sadly, the great chamber is a library – albeit quite a big and beautiful one – and the “gallery” is really no more than a landing, but Walpole deliberately arranged for the light to be gloomy just there so with a bit of effort of the imagination you can transport yourself from Twickenham to Italy and the cursed Castle of Otranto.

Further Reading

If you are interested in some of the themes underlying the book and the building, you might like to look at Reeve’s 2013 article on “Gothic Architecture, Sexuality, and License at Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill.” (The Art Bulletin, 95(3), 411-439.) There’s a lot of dubious pretension in the paper, which is not an easy read, but it does argue that both the book and the building were ways in which Walpole explored his sexuality. There is, indeed, quite a strong Freudian subtext in the book, which I have not explored in this blog post. The pictures of the Castle of Otranto and the staircase at Strawberry Hill are both taken from Reeve’s paper (worth a look for the illustrations alone). Reeve credits them as public domain artwork, photographed by the Lewis Walpole Library at Yale University.

by TCW | Feb 5, 2019 | Book review

‘The Wolf and the Watchman‘ publishes on Thursday and the Sunday Times carried a long review this weekend. Thanks to NetGalley, I was sent an advance copy of the book, so I’m able to review it today.

It’s 1793. Sweden is a major military power in the region and has recently been at war with Denmark, Norway and Russia. Internally the king has been assassinated. Revolution is breaking out in France and there are fears it will spread throughout Europe. Life, it is fair to say, is not a bundle of laughs.

When the limbless corpse of a young man is pulled from the sewerage that pools in the rivers that Stockholm is built on, Mickel Cardell, a drunken watchman, ends up working with the lawyer, Cecil Winge, to find out who is responsible for the crime.

You could reasonably say that this is a detective story. In Winge it has a detective and, eventually, the crime is solved, but this is a detective story like no other I have ever read. Winge’s investigations take the reader into the underbelly of late 18th-century Stockholm with a degree of detail that means I would not encourage you to read the book too soon after a full meal. Sexual sadism, common or garden sadism, brutality, starvation, fraud, robbery, rape – these are the everyday facts of life and Niklas Natt och Dag spares us no details. Cardell and Winge are both, in their own ways, trying to be good people, but they admit that their city is, in truth, beyond redemption.

The story should be profoundly depressing, but somehow it is not. Cardell and Winge are both fascinating characters. Cardell has lost an arm fighting the Russians and is constantly haunted by the guilt of surviving a battle that saw his closest friend die. Winge is dying of consumption. Both seek some sort of redemption by solving this crime, the more so as they come closer to understanding the prolonged horror of the victim’s death.

Winge is a rationalist, convinced that some sort of order can be imposed on the world by logic. Cardell is more emotional. Neither alone has any hope of success, but together they make progress.

The characters they meet on the way are as crucial to the success of the novel as is the plot. There is the young would-be surgeon, who loses his money in a gambling fraud and is trapped into becoming complicit in the long slow death of the victim. There is the young woman who turns away a man’s advances and, in revenge, is denounced as a prostitute. It is the meeting of these two which provides one of the few genuine opportunities for redemption in the book. (It’s a measure of the general misery that the act of redemption involves suicide, but then we can’t have everything.) And there is the evil villain – a man so comprehensively repellent that only a detailed back story including his even more repulsive father makes him at all credible. Sadly the quality of the writing means that he is all too credible indeed.

Yet, against a background of almost unremitting bleakness, The Wolf and the Watchman allows moments of light, the more intense for the darkness that they illuminate. Cardell finds the opportunity to save one innocent life, Winge discovers that sometimes rationality has to give way to the imperative to do the right thing. One of the guilty is punished, which is, as I’m sure Winge would argue, is better than nothing. One, at least, of the innocent is saved (as are several of the not-quite-as-guilty – but it’s the 18th century, what did you expect?)

Stockholm remains a mix of great beauty and incredible squalor. The corruption that taints every layer of society is about to be challenged as Europe trembles on the brink of Revolution and War (though an interlude in Paris makes us realise that one set of vices will simply be driven out by another). Winge, waking covered in blood will be dead in days, if not hours. Cardell, by contrast, may have found redemption in this life.

This is not a cheerful book, but it is a very, very good one. I recommend it wholeheartedly.

The Castle of Otranto from an illustration in the original book. Rather larger than Strawberry Hill

The Castle of Otranto from an illustration in the original book. Rather larger than Strawberry Hill