by TCW | Aug 20, 2019 | Book review

Every so often I “buy” a free book on Amazon which is being promoted in the hope of getting some reviews. If I read a book like this and I like it, I feel that I really should review it. That’s only fair, isn’t it? I hope you do the same.

Anyway, the latest random book picked up like this was Tannis Laidlaw’s ‘Half-truths and Whole Lies’. Here’s the review.

———————————————————–

Sophie Rowan has left an American university to lead a research project at a prestigious medical school in London. There she discovers, to her amazement, that her professor takes credit for the work done by other researchers on her team.

This is an enjoyable tour of an aspect of academic life that anyone who has worked in a university (I’ve dabbled and my wife has worked as an academic) will recognise. The evil professor in this case is more blatant than most, simply plagiarising her students’ theses and publishing them under her own name, but I am surprised that Laidlaw’s protagonist is shocked to learn that professors don’t always properly credit work done by others in their departments. (I hasten to add that the academics I’ve worked for have been generous with credit, but this is far from a universal experience.)

Sophie Rowan’s journey from dewy-eyed innocence to an understanding of just how Machiavellian university politics can be makes for an excellent read. At the same time as she is learning the realities of academic life, she is also exploring her new home in London. As a Londoner, I enjoyed seeing my city as experienced by a foreign visitor. Sophie Rowan’s London is well observed and it is clear that the author, too, has seen London as an outsider. The confusion that Sophie feels when offered “nibbles” is just one example of the fun that Laidlaw has with this.

This is quite a layered book. Sophie has rather a busy back-story and she has to sort out family issues and her love life as well as deal with university politics. There’s so much going on it’s easy to get very involved with the character and I did enjoy the story. As it goes on, and the evil professor is revealed as a sexual predator as well as a plagiarist, things get a bit melodramatic, culminating in a stand-off between somebody who can be legitimately described as psychotic and somebody who shows many of the attributes of a psychopath. A butcher’s knife features. It’s a slightly rushed and over-the-top ending which I found a bit unsatisfying, but those who want to see good triumph and evil carted away in handcuffs should enjoy it.

by TCW | Jul 23, 2019 | Book review

I’ve never reviewed two books by the same author in successive weeks before, but I’m happy to make an exception now.

My review of Frank Prem’s ‘Small Town Kid’ came out last week. Frank was pleased to see that I liked it, so he sent me a copy of his next, ‘Devil in the Wind’. It’s another book of free verse, this time inspired by the 2009 bushfires in Australia.

I generally take my time with poetry books, but I opened this one to make sure that my Kindle copy had downloaded properly and I was immediately gripped. I read it over the next couple of days, hardly an achievement because poetry books don’t have that many words in them, but not the way I would usually approach poems at all.

I found the work immensely moving. Frank does, admittedly, have spectacularly moving source material, but I vaguely remember reading about it in newspapers time and the naked facts don’t have the same gut wrenching impact as these verses.

As I said last week attitudes to poetry are inevitably subjective, and perhaps you won’t feel the same way about them as I did. If you go onto Amazon, though, ‘Look inside’ will let you read all but the last page of his ‘Prologue’ which grabbed me by the throat and pretty well forced me to read on. All I can suggest is that you do just that. If you like it, please buy the book. It’s wonderful.

by TCW | Jul 16, 2019 | Book review

When Frank Prem offered me a copy of his “free verse memoir” through a writers’ Facebook group I wasn’t at all sure that I wanted it. But then I reckoned the idea was so outrageous that I might as well read it anyway and I’m ever so glad that I did.

I wouldn’t exactly think of it as a free verse memoir. It’s definitely free verse – the absence of all punctuation and capitalisation gives it a very 1960s feel that I’m not sure improves it – but it’s not exactly a memoir. Rather it’s a chronological series of poems describing the author’s life growing up in small-town Australia. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book of poems and felt enthusiastic about all of them. There is a strong subjective element to poetry and what pleases one person won’t please another, but there are some real gems here. He captures a lot of the ambivalence of a young child’s feelings about life. He captures, too, a vanished way of living. There are poems about the dubious charms of the outhouse and the odiferous work of the night-soil men and then, later, a poem about the blasting of a sewerage line heralding a new world:

of filtration

and treatment plant

and of sculpted porcelain

It is, the title of the poem assures us, “the dawn of civilisation”.

There is a strong sense of place and time – not only the period, but slow cycle of the seasons and the events that mark their passing in this small town. Here’s the church fete:

once a year

it happens once a year

the noise shatters the afternoon

as an old ute with two loudspeakers attached above the roof of the cabin

does circuits of the town

and can be heard in a garbled blur

from three streets off

and not much better up close

but it doesn’t matter what they’re saying

because we already know

And bonfire night:

a couple of tuppenny bangers

and a short detour

to blow up the deputy headmaster’s mailbox

is an annual event

and he’s long practised

at straightening its swollen metal sites

on the morning after

As Frank grows older (there’s a nice poem called ‘growing pains’) girls feature more often, from the gentle innocence of ‘sweet maureen’

I rode my bike for sweet maureen

from beechworth to yackandandah

…

I was drawn

down the road

descending like a bullet

from the barrel of my rifle

drawn to ride

to sweet maureen

to the rather less innocent Judy.

judy runs the supermarket now

but I remember her as fifteen years

of laughing dark-brown eyes

that once upon a time

closed to kiss me

on a new year’s eve

in a crowded street

that vanished

for the whole

of one

single

moment

As the book goes on, the sad reality of the lives of some of these women is cruelly exposed, like the popular girl at school who

… stopped coming

to classes

then moved away

before the baby arrived

Eventually, though, there is love:

hey I think we’ll get by

won’t our folks

be surprised

they think that we’re lost

but I don’t suppose

we’re so bad

and a child.

I watch over

my tiny wonder

Despite the pessimism that slips in through many of the poems

we were formed

as small-town kids

was there ever a chance

this is, in the end, a life affirming collection of poems. I’m glad I took the chance to read it.

Small Town Kid is available on Amazon in paperback or as an e-book: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B07L63WS2D

You can hear Frank reading some of his poetry on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvfW2WowqY1euO-Cj76LDKg

Frank’s second book, Devil in the Wind (poems inspired by the bush fires of 2009) is also available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B07Q9YLD8V

by TCW | Jul 9, 2019 | Book review

A Plague on Mr Pepys is the second of Deborah Swift’s stories based on the lives of women mentioned in Samuel Pepys diaries. (I reviewed the first in the series HERE.) While Pepys featured heavily in the first book, here he is a more peripheral figure and the story centres on Bess Bagwell, the mistress most often mentioned by Pepys in his diaries. Not a lot is known about her (even her given name comes from Swift’s imagination), which gives Swift free rein to tell a story set amongst the working folk of London. Bess has risen from the whorehouses of Ratcliff to marry a skilled carpenter and be mistress of her own home in Deptford. But life in 17th century London is always precarious and when her husband falls foul of the Guild system and can’t get work in the shipyards, they move rapidly into debt.

This is not a cheerful story. Bess Bagwell’s descent from happily married housewife to debt-ridden homelessness is painfully detailed. Survival in the 17th century depended a lot on family, but families can turn against you if you think you are better than they are and both Bess and her husband have flown too high to rely on the family support that might have saved them.

Bess moves from housewife to working in a glove factory, to taking on piecework and, finally, to unemployment. Somewhere along the way she finds herself trying to save the family finances by trading sexual favours for patronage from Mr Pepys. It seems she hasn’t quite escaped the whorehouse after all.

If things seem bad, there’s still the plague to come. With characters seeming to die on every page, Bess begins to accept that she may well not survive. Worse, it’s not entirely clear that she wants to.

Is there any chance of a happy ending? Well, all things are possible, which is pretty well all that kept me going. It’s a harrowing look at the reality of 17th century life, benefiting from Swift’s considerable expertise in the period. (Sadly this expertise does not extend to naval conflict – an area that I know from experience is all too easy to slip up on. Fortunately most of the story stays firmly on land.) It’s far from an easy read, but with so many novels that romanticise the 17th century, this is a useful antidote – and, if you can stick it – a book that looks long and hard at love, marriage, and family loyalty.

Swift’s writing is fluid and kept me going through difficult subject matter. Even so, this is not an easy book, but one which definitely repays the effort you put into it. Despite the misery, I am happy to recommend it.

by TCW | Jun 4, 2019 | Book review

When I agreed to review Rees-Mogg’s book, The Victorians for the Historical Novel Society I hadn’t seen the tsunami of negative reviews that it has received. When it arrived I approached nervously, both because it’s a bit unnerving to settle down with a 439 page book that everybody has said is awful, and because if I didn’t like it either, what on earth was I going to say in the review?

The book is indeed terrible. But I think that many of the reviewers have done it something of an injustice. Rees-Mogg has set out to discuss the lives of twelve Victorians – “Twelve Titans Who Forged Britain” – and this has led most people to see this book as essentially a history of the Victorian age seen through some of its leading figures. I think this fundamentally misunderstand is what Rees-Mogg is trying to achieve.

Jacob Rees-Mogg

Jacob Rees-Mogg

The book is not in any normal sense a historical work. It does have some history, but this is used merely to illustrate Rees-Mogg’s view of the world and, given the significant role he plays in our current politics, understanding his view of the world is probably a worthwhile undertaking.

Rees-Mogg appears driven by two things – his Catholicism and his membership of the Conservative Party. The book does give me a much better understanding of the history of the Conservative party and the way that it developed during the 19th century. In fact, I suspect that Rees-Mogg could write a useful book about the party. He explains how Peel’s Tamworth Manifesto (1834) “marks … the beginning of the contemporary British Conservative Party”. It was a serendipitous moment to shape a political party because “The General Election of 1835 … was the first election when papers published lists of candidates with ‘party’ labels attached.” Peel went on, of course, to split the party over his repeal of the Corn Laws and Rees-Mogg’s explanation of the background to this and the way in which the party eventually recovered from the split is a useful summary for those of us who are vaguely aware of what happened without being clear as to the detail. It would be clearer still if this was arranged as a straightforward history of the party rather than having the split in a chapter about Peel and the details of the recovery in a much later chapter about Disraeli. Even so, the history of the party is well presented. For anyone who, like Rees-Mogg, cares about these things, Disraeli’s consolidation of the party’s organisation is a significant historical event.

“It was at this time Conservative Central Office evolved as the prime organisational power in the party with sub-bodies established to reinforce its power and influence in the country. One such was the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations, that tentacle of Central Office in charge of organising within newly enfranchised urban communities…”

Sadly, Rees-Mogg is not writing a history of the Conservative party, but the lives of twelve great Victorians. The obsession with the party leads to some distortions so extraordinary as to be almost comic. So these are the closing words of his chapter on Peel:

“In the end, it is only possible to recognise the majestic extent of Peel’s achievement by realising what it avoided. For without the party and its philosophy he bequeathed to the nation, there is little reason to suppose we would have coped with change any better than other countries did. A negative achievement when seen in full, perhaps, but a vital one, and one for which we should still be thankful.”

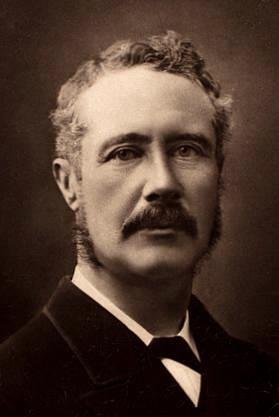

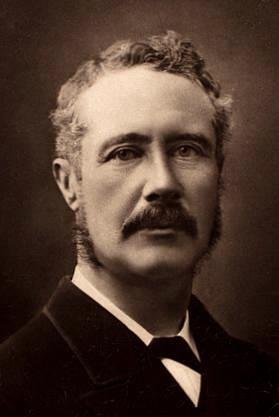

Robert Peel

Robert Peel

Peel’s political career started as Chief Secretary to Ireland. He was the chairman of the Bullion Committee that returned Britain to the gold standard. As Home Secretary he founded the Metropolitan police, and is widely regarded as the father of modern British policing. As prime minister he was responsible for, amongst other things, the Mines and Collieries Act 1842, the Income Tax Act 1842, the Factories Act 1844 and the Railway Regulation Act 1844. Whilst historians recognise his achievement in shaping the modern Conservative Party, Rees-Mogg’s emphasis on this aspect of his career appears excessive.

When he is not viewing his subjects through the lens of his political interests, Rees-Mogg concentrates on their religious views. Pugin, for example, is included as one of the “twelve Titans”. Even if you are a fan of his architecture – and as Rees-Mogg admits, “Even in his own lifetime … his people virtually lost sight of his achievement” – it is difficult to see the basis on which he is one of the twelve most important men of his time. The answer is that he was “God’s architect”, his designs intended to reflect the glory of a Catholic (or, when occasion demanded, an Anglo-Catholic) deity. Gladstone’s Whiggery is forgiven for the “deeply felt sense of religion” that influenced his outlook. He was a High Anglican who fought for disestablishment of the Anglican church in Ireland (favouring the Catholic cause) though for ten years he refused to speak to his one-time friend, Manning, who had been an Anglican cleric before converting to Catholicism eventually becoming Archbishop of Westminster.

Pugin was mainly responsible for the interior detailing of Parliament, but he did design the clock tower

It is with the chapter on General Gordon that the discussion of religious beliefs carries us to the edge of sanity. Gordon was far from the most important martial figure of his age. He fought in the military shambles that was the Crimean War and then beat the Chinese in the Second Opium War, a conflict in which the technological superiority of the European armies meant that the outcome was never in serious doubt. Still in China, he assisted the Chinese government in putting down the Taiping Rebellion before (with British government approval) entering the service of the Khedive of Egypt in 1873 where he became Governor-General of the Sudan. He stayed in the Sudan until 1880, when he returned to England. However, a rebellion in Sudan led to Gladstone’s government deciding to withdraw all British and Egyptian troops and administrators in the upper Nile Valley. Gordon objected and went to the press advocating massive intervention in the Sudan to crush the uprising. Public opinion backed him and Gladstone, feeling he was losing control of the situation, agreed that Gordon could go to Khartoum and report but the government policy was to continue to be an evacuation of British and Egyptian personnel. On his arrival at Khartoum, Gordon ignored his orders and began preparations for a siege. His position was militarily impossible. Again, public opinion took his side, insisting that a relief force be sent to break the siege. It arrived too late. By the time the British arrived the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed. About 10,000 people died in the course of the assault.

General Gordon

General Gordon

It can be argued that Gordon’s military career, despite his popularity with the public, was unimpressive. What makes him stand out for Rees-Mogg seems to be his religious beliefs.

“In this chapter, the aim is to re-examine this British exemplar… In particular to emphasise the forgotten aspects of his story, his deep and unique religiosity…”

What Rees-Mogg sees as a “deep and unique religiosity” most 21st century readers may well view as barking mad.

“He came to believe in the pre-existence of the soul. The body was a ‘sheath’ in which the soul was placed at birth, to be awoken when union with Christ was achieved… [O]nce this vision occurred ‘the now raised and quickened soul will grope its way out of its shell’ where … it will contend with the body, often being nearly extinguished but never quite, till the body gives up the struggle in natural death’ and the much longed for homecoming is achieved.”

Bluntly put, Gordon had a death wish. Rees-Mogg reports him as saying, when threatened by King John IV of Ethiopia:

“I am always ready to die, and so far from fearing you putting me to death, you will confer a favour on me by so doing, for you will be doing for me that which I am precluded by my religious scruples from doing for myself.”

In Khartoum, Gordon finally achieved the end he had sought so enthusiastically for so long. It is just unfortunate that 10,000 others had to die alongside him.

Why does Rees-Mogg enthuse about somebody who appears not only, to put it mildly, eccentric, but dangerously eccentric? The answer appears to be that the author holds many beliefs that have more in common with those held by the Victorians than one might expect to find in a 21st century Member of Parliament. He is obviously a believer in the Great Man theory of history, but he also believes that Providence plays a direct role in guiding historical events. Writing about Sleeman (famous for first discovering and then eliminating Thugee in India) he says:

“… perhaps fate or destiny had ordained precisely that Sleeman be on the spot, for it needed such a man as he to deal with a situation that so many before him had failed to resolve.”

Rees-Mogg’s vision of Conservatism and his religious beliefs are firmly rooted in his view of the 19th-century, but this is a 19th century than never really existed. The Victorians seeks to delineate a myth:

“These heroes of old who possessed belief and patriotism, a sense of duty, a confidence in progress and knowledge of civilisation have shown us what can be done… The truth is that Victorian Britain was [… a society of] greatness, nobility, and good sense.”

Like all myths, it depends on willing acceptance by its audience. Mythology is not about fact and detail – hence, presumably, the absence of footnotes, references (there is just a bibliography of three pages of secondary sources), or even an index. Instead we have a broad brush overview of twelve of Rees-Mogg’s heroes. They are not, even by his own account, particularly representative. Discussing the Jamaica Committee, he lists “some of the most illustrious worthies of liberal Britain … Charles Darwin, John Stuart Mill and the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley.” None feature in this book, their liberalism alone being enough to disqualify them. The book ignores, or dismisses out of hand, most controversial issues. (My personal favourite was that “the First Opium War proved an unqualified British success… A Second Opium War (1856-60) would complete the mission to British satisfaction.” This casually dismisses probably the most outrageous aggression of a century that provides stiff competition in this field.)

Sadly, the fantasy idyll of Victorian England was cruelly facing reality even while the book was being printed. For Rees-Mogg, the great strength bequeathed to us by the Victorians was the stability of our political system and our constitution.

“… the unique characteristics and glorious flexibility of the British constitution. This was an entity which could, unlike its known, codified equivalent, respond swiftly and decisively to the political needs of the nation.”

As Britain and its political class become the laughing stock of the world, it is worth knowing that one of the architects of our national humiliation is a man whose beliefs are based on a badly researched, carelessly presented, largely imaginary past. Rees-Mogg’s vision of the Conservative Party – a vision that Peel and Disraeli would both recoil from – and his messianic conviction that Providence will step in when the nation needs to be saved, both make him utterly unfitted for public office. If this book has only made that clear, reading it is not time entirely wasted.

Image credits

Jacob Rees-Mogg: official photograph by Chris McAndrew

Peel: Duyckinick, Evert A. Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women in Europe and America. New York: Johnson, Wilson & Company, 1873. Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

Big Ben: Photo by DAVID ILIFF. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Gordon: Geruzet Frères – Belgian (active c. 1870-1889) – Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum, Historical Photographs and Special Visual Collections Department, Fine Arts Library

Why am I writing this?

I’m not an expert on the Victorians. Victoria was on the throne a long time and a lot happened then. But my books about John Williamson are set mainly in the 1850s and their theme is the contradictions and complexities of Empire and the Victorian age. It is fair to say that they give a rather more nuanced view of this period than Rees-Mogg (and feature some rather more interesting Victorians, including James Brooke, whose inclusion would have made Rees-Mogg’s book a lot more interesting). If you want to know more about this series of books, please have a look at my blog post on the Williamson Papers.

by TCW | Apr 16, 2019 | Book review

At the end of last year I reviewed ‘Dear Laura’ by Jean Stubbs. It was presented as a detective story, but I said in my review that I felt that it was more of a psychological thriller, so when the publisher (Sapere) offered me a sequel featuring the same detective I was intrigued as to what sort of a book I would be reading.

‘The Painted Face’ is, again, more an exploration of the mind of one of the protagonists than it is a conventional detective story.

Carradine is an artist: a man gifted with great technical skill, but unable to express himself as he would wish. In both his painting and his personal life he is unable to give vent to any real feelings. His emotions are trapped as the child he was when the step-sister he adored was killed in a train crash and his stepmother (Gabrielle), for whom his feelings were practically oedipal, subsequently died of grief.

He decides that the only way he can move on is to understand the mystery of his sister’s death. The circumstances had never been properly explained. Why was the child, whose mother was devoted to her, travelling apparently alone on a train from France to Switzerland? Why was the mother’s maid summarily dismissed soon after?

Inspector Lintott (from the previous story) has retired, but Carradine hires him to dig up the past. They travel together to Paris, where Gabrielle’s family had lived and where she spent much of her time with them. It was from there that Odette, the sister, had set off on her fatal journey.

The dedication of the book mentions Paris and the city is clearly a character in the book. It’s 1902 and Paris is at the height of its fin-de-siècle splendour (as Carradine would see it) or degeneracy (as Lintott definitely suspects, at least initially). The book is a celebration of the honest enjoyment of good food, good company, and good sex which Stubbs ascribes to the Paris of the period. She does the food and the company rather well and the sex, where discreetly touched upon, is nicely sketched too, but there is a gaping hole where Paris ought to be. There are no smells (though the sewers then were presumably even more odiferous than they often are now); there is little sense of the noise of a busy city full of cobbled avenues. We do not gaze through the windows of the shops of the Champs-Élysées and, although there are often descriptions of individuals encountered on the streets, we get no sense of the hustle and bustle, the colours or the swirl of movement.

In ‘Dear Laura’ Stubbs showed herself mistress of the domestic. Almost all the story takes place in one house and the mild claustrophobia of the setting adds to its strength. The best bits of ‘The Painted Face’ are also those which take place in quite intimate settings: the painter’s studio; a mistress’s boudoir; even the attic of Carradine’s home. The attempts to paint on a broader canvas – a journey across a peculiarly anonymous France; the walks around Paris – these simply distract from a story that is really about Carradine and his attempts to come to terms with his demons.

In the end Lintott solves the mystery and Carradine does find closure. It’s not really a detective story at all – most of the mystery is solved when he reads Gabrielle’s diaries which Carradine, despite going to the trouble of hiring a detective, has never thought to read himself. And the story is finished neatly by a series of improbable coincidences which would have embarrassed Dickens – surely the father of improbable literary coincidences. The final twist, too, is rather pat and predictable, but it does provide a satisfying ending.

This is a well-written story with some nice characterisation. Not only the tormented artist and the apparently stolidly conventional detective are well-drawn but so are the minor characters: the garrulous old lady who provides a vital clue tucked away in her apparently unending reminiscences; the restaurant owner who helps Lintott negotiate his way through a menu he cannot read; the servant with an active fantasy life who, in the real world, is constantly falling pregnant.

There is much to enjoy, but, taken as a whole, I felt it didn’t quite work. That may be just me: in any case, the time spent reading was not wasted and you may well enjoy it more than I did.

Jacob Rees-Mogg

Jacob Rees-Mogg Robert Peel

Robert Peel

General Gordon

General Gordon