by TCW | Oct 26, 2018 | Napoleonic history

While I was writing here about Waterloo, I had a suggestion that I wasn’t paying enough attention to the human cost of the battle. I promised I would come to this and we’ve not talked about Waterloo for a while, so this week might be a good time to come back to the battle and. more particularly, its aftermath.

Waterloo was far from the bloodiest battle of the Napoleonic wars (that dubious distinction belongs to Borodino). However, the number of dead in such a small field was horrific. An idea of what it was like can be gathered from this account by an anonymous private soldier:

In the first place, the ground, whithersoever we went, was strewed with the wreck of the battle. Arms of every kind, cuirasses, muskets, cannon, tumbrils, and drums, which seemed innumerable, cumbered the very face of the earth. Intermingled with these were the carcasses of the slain, not lying about in groups of four or six, but so wedged together that we found it impossible in many instances to avoid trampling them, where they lay, under our horses’ hoofs; then, again, the knapsacks, either cast loose or still adhering to their owners, were countless. I confess that we opened many of these, hoping to find in them money or other articles of value, but not one which I at least examined contained more than the coarse shirts and shoes that had belonged to their dead owners, with here and there a little package of tobacco and a bag of salt; and, which was worst of all, when we dismounted to institute this search, our spurs forever caught in the garments of the slain, and more than once we tripped up and fell over them. It was indeed a ghastly spectacle, which the feeble light of a young moon rendered, if possible, more hideous than it would have been if looked upon under the full glory of a meridian sun; for there is something frightful in the association of darkness with the dwelling of the dead; and here the dead lay so thick and so crowded together, that by and by it seemed to me as if we alone had survived to make mention of their destiny.[1]

Print of William Frye’s painting of Waterloo after the battle

Print of William Frye’s painting of Waterloo after the battle

The French had specialised sprung ambulances to transport their wounded, but in the chaos of the French defeat their wounded were abandoned on the field. As darkness began to fall, the victorious allies began to sort the living from the dead, carrying those who could not walk in whatever carts they could find.

We found on every side poor fellows dying in every variety of wretchedness, and had repeatedly to join the strictest silence that we might hear their scarcely audible groans … Before morning we collected several wagon-loads of brave fellows, friends and foes. [2]

Whilst the Allies did attempt to remove the casualties and give them medical care, the sheer scale of the exercise meant that people lay in the open for days – by which time, of course, most of them were already dead. Only after the Allied troops had been cared for did the British turn to the French. An anonymous Staff officer who was there wrote:

I have reason to believe it was not till the fourth day after the battle that the last of the French were taken up; and it is painful to think of the suffering they endured from pain, cold, and even hunger, during so many weary days and nights, – numbers of them, doubtless perished who would have survived had they been taken care of. Neither does it appear that any food was regularly supplied to them … [3]

The British had set up a field hospital at Mont St Jean in a big farmhouse that still stands today. This is an account of the site by a sergeant of the Scots Greys:

We having arrived at the farmhouse, Mont St Jean, which is situated on the road in short distance in front of the village of the same name, entered the yard, where a most shocking spectacle presented itself. This house and yard, during the time of the battle, had been occupied by some of the British and Belgic surgeons and in it many amputations had been performed. A large dunghill in the middle of the square, was covered with dead bodies and heaps of legs and arms were scattered around! A comrades who stood near me on entering unconsciously muttered “Oh God. What a sight.” To which I made no answer, but felt as he did, for a great number lay by the sides of the house and basked in the beams of the sun who had only life’s last spark remaining and gasped for relief. [4]

The farmyard at Mount Saint Jean as it is today

The farmyard at Mount Saint Jean as it is today

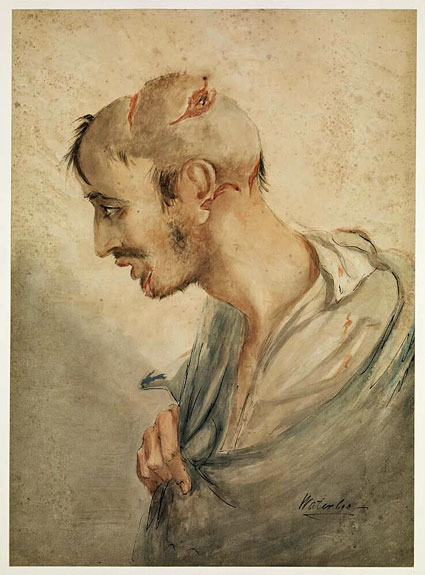

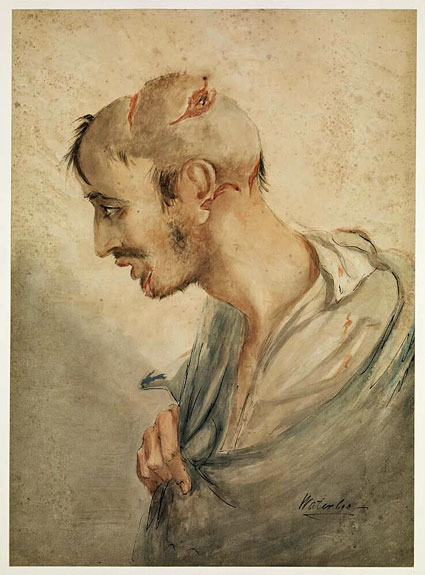

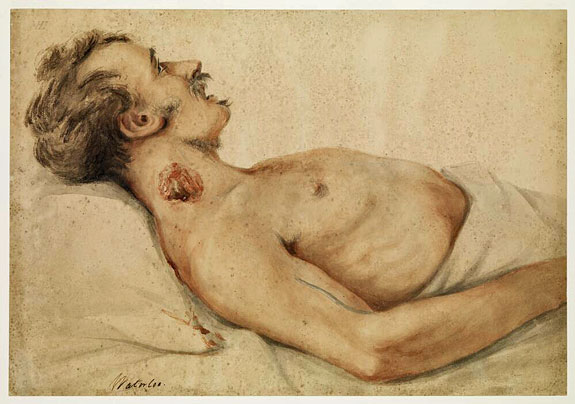

Here the surgeons had to deal with a range of injuries. The Scottish surgeon, Charles Bell, who was operating on French soldiers in the Gendarmerie Hospital, made detailed watercolour paintings of the sort of things treated at Waterloo.

Sabre wound to head. (Wellcome Library) Grapeshot wound to the neck (Wellcome Library)

Most wounds were caused by gunshot and the main concern of the surgeons was to remove the ball and ensure that the wound was left clean. Usually the ball would have carried fragments of clothing into the wound and these had to be carefully removed one by one with forceps. Remember that this would have been done while the patient was fully conscious.

A major cause of death was infection. Gangrene was a particular problem. Without antibiotics the only way to treat wounds that were liable to turn gangrenous was by amputation. Arms and legs were cut off with gay abandon. There was a pile of detached limbs in the courtyard shown in the photograph above.

I observed with some warmth of national feeling, several highlanders’ legs, still wearing the emblem of their country; Auld Scotia’s tartan hoe! As also the legs of dragoons in boots and spurs and many others which still wore a part of the garment in which they had proudly paced the causeways of their native land. [5]

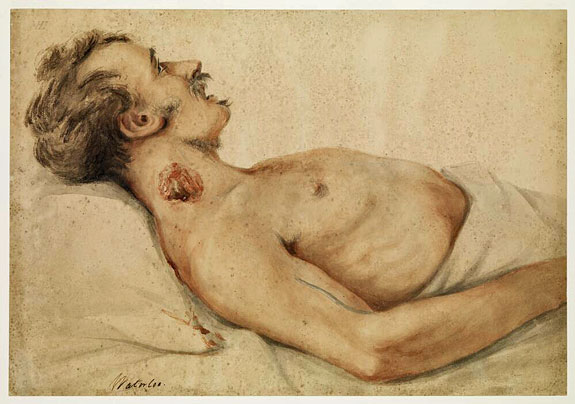

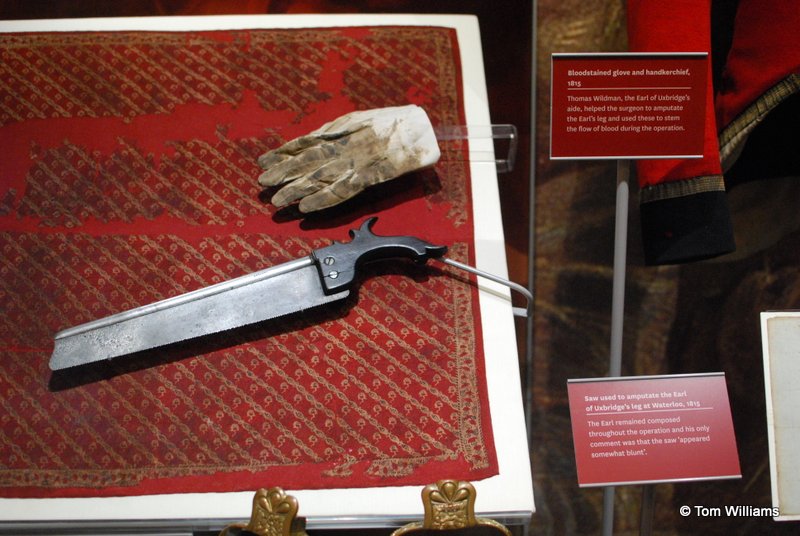

The secret of a successful amputation was that it should be done very fast. A sharp bone saw was crucial to a surgeon’s success rate. The photograph below shows the saw that was used to remove the leg of the Earl of Uxbridge, who had been hit by a cannon-ball while sitting on his horse alongside Wellington.

Bone saw displayed at National Army Museum

Bone saw displayed at National Army Museum

Surgeons had to work quickly so that their patients did not die of shock as they went through the amputations unanaesthetised. But there was another reason for speed as well. There were only 270 surgeons available to treat the wounded, and with tens of thousands of men requiring attention they had no time to spend on any but the most basic of procedures.

As the wounded were moved from the battlefield, so Brussels filled with makeshift hospitals. Soldiers who were less badly injured were cared for in the parks, because all the buildings were full, with contemporary accounts claiming that every private house had three or four wounded soldiers in it. [6] Modern authors estimate that around 62,000 Allied and French wounded flooded into Brussels, Antwerp, and other towns and cities of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. [7] The scale of the horror was such that a British tourist (himself an ex-Army man) wrote ten days after the battle:

You may form a guess of the slaughter and of the misery that the wounded must have suffered and of the many that must have perished from hunger and thirst, when I tell you that all the carriages from Bruxelles, even elegant private equipages, landaulets, barouches and berlines, have been put in requisition to remove the wounded men from the field of battle to the hospitals, and that they are yet far from being all brought in. [8]

References

- Quoted by Gleig in his Story of the battle of Waterloo p253

- Augustus Fraser: Letters of Colonel Sir Augustus Simon Frazer, K.C.B. commanding the Royal horse artillery in the army under Wellington, Written during the peninsular and Waterloo campaigns

- Recollections of Waterloo by a Staff Officer United Service Magazine 1847 PartIII p355

- Sgt William Clark, whose writings have recently been published as A Scots Grey at Waterloo edited by Gareth Glover

- Ibid

- After Waterloo – Reminiscences of European Travel 1815-1819 by W E Frye

- See, for example, Michael Crumplin and Gareth Glover (2018) Waterloo – after the glory

- Frye ibid

To be continued …

There is more about the aftermath of the battle in next week’s blog.

by TCW | Sep 14, 2018 | Napoleonic history

There has been a huge amount of interest in my post on cavalry at Waterloo, so I’m going to briefly revisit it.

It was during the charge of the Scots Greys that the French lost one of their regimental colours. Losing your colours was a very big deal – captured colours were listed in battle reports alongside the number of enemy dead and the number of their cannons you had captured. To lose your regimental colours was a huge disgrace and the colours would be entrusted to a junior officer supported by some of the biggest and strongest men in the regiment who acted as bodyguards. French colours were referred to as ‘Eagles’ from the gilded eagle that topped the staff that carried the flag. Eagles were awarded to regiments by Napoleon personally.

Sergeant Ewart was, by all accounts a big man and a noted swordsman. He was carried along by the charge and found himself closing on the colours. He cut down the standard bearer and two bodyguards, writing later, “I had a hard contest for it.” His commander ordered him to the rear, carrying the Eagle off as a trophy.

Sergeant Ewart was later promoted to Ensign because of his valour at Waterloo. An Ensign is the most junior officer but this was at a time when it was rare to rise from the ranks.

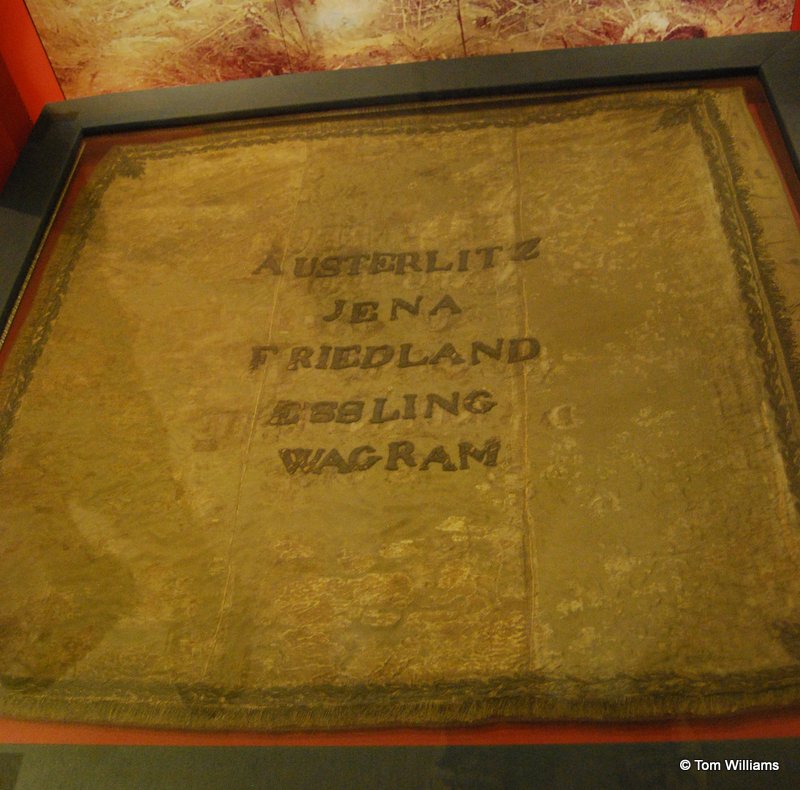

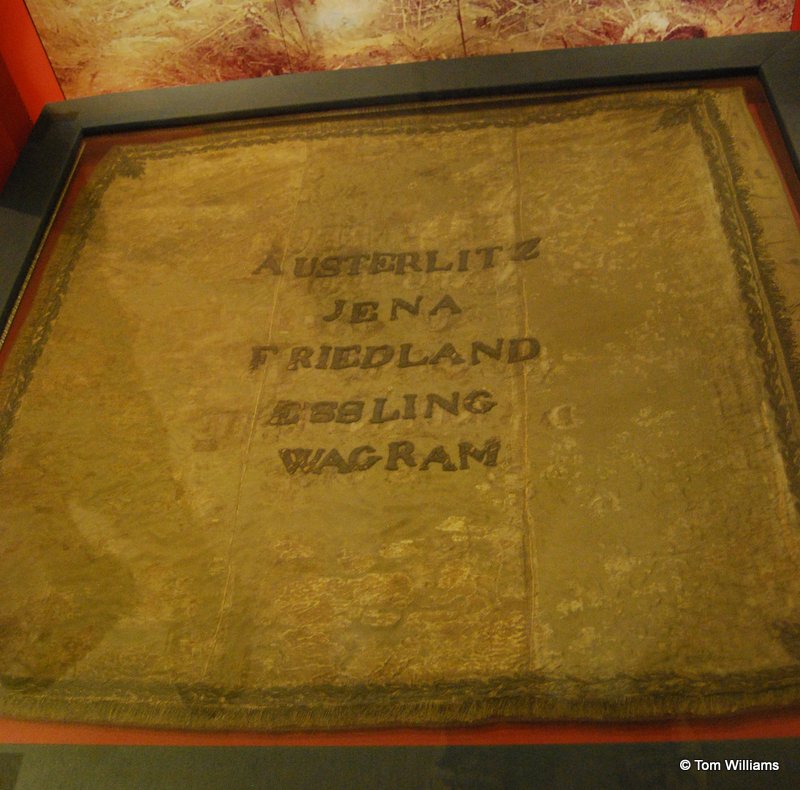

The Eagle (with its ‘45’ indicating that it belonged to the 45th Regiment of the Line) is now in the regimental museum of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards in Edinburgh Castle, as is the standard of the regiment with its battle honours embroidered on it.

The Royal Scots Greys incorporated the Eagle into their cap badge and their successor regiment, the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards wears the eagle and the battle honour ‘Waterloo’ to this day.

Ewart’s capture of the Eagle caught the public imagination and is the triumph that everybody remembers today, but that was not the only Eagle captured at Waterloo. The Royal Regiment of Dragoons (like the Scots Greys, part of the Union Brigade) captured the standard of the 105th. One reason that this made less impact is probably that there was an acrimonious argument about who actually captured it, which took some of the gloss off the achievement. The credit was given to Corporal Stiles (or Styles) who returned to the Allied lines with the flag, but Capt Alexander Clark claimed that it was he who had struck down the officer carrying the flag and that he had then ordered Stiles to take it from the field. Another officer later claimed that it was actually him who had captured the flag, though this claim, made very late in the day, is generally disregarded. After enquiries made by the regiment, Stiles was given official credit for the action, a decision which Clark disputed for the rest of his life. It seems that in the heat of the action, with both men close to the standard and struggling to take it from the bearer, no one will ever be quite sure what happened. It’s a good example of why people who claim to be certain of anything that happened in the heat of battle are deluding themselves.

Standard of the 105th (National Army Museum)

Standard of the 105th (National Army Museum)

Stiles, as a mere corporal, was promoted as a result of the capture. Like Ewart he ended his career as an Ensign, but in a West India Regiment (not a particularly desirable posting). Clark, on the other hand, ended up as colonel of the Scots Greys.

Malvern Festival of Military History

Waterloo will feature at the Malvern Festival of Military History with talks on Napoleon and on the battle on the final day, Sunday 7 October. I’m appearing on the same day, talking about turning historical fact into fiction. The festival looks to be an exciting three days with talks on everything from Agincourt to Vietnam. Tickets are still available.

by TCW | Aug 24, 2018 | Napoleonic history

By the end of the 18th century, the main role of cavalry was to pursue and destroy a fleeing army. It also provided a mobile force that could be moved to support infantry in moments of crisis.

At Waterloo, as probably in some other battles, the cavalry, often held back behind the infantry, could be used to turn back units that were trying to flee the field – not a noble role, but an important one nonetheless.

The British cavalry was recognised as being brave and well mounted, providing a powerful force capable of inflicting significant damage on an opponent, but prone to getting, literally, carried away. Cavalrymen and their mounts tended to get caught up in the excitement of a charge and often overran the enemy lines significantly reducing their effectiveness on the field of battle. Wellington was famously suspicious of his cavalry.

“[There is] a trick our officers of cavalry have acquired of galloping at everything, and then galloping back as fast as they gallop on the enemy. They never … think of manoeuvring before an enemy – so little that one would think they cannot manoeuvre, excepting on Wimbledon Common; and when they use their arm as it ought to be, viz. offensively, they never keep … a reserve. All cavalry should charge in two lines, of which one should be in reserve…”

At Waterloo, Wellington generally held his cavalry back and when they did charge the result (as we shall see) was impressive but sometimes doubtfully effective.

The French cavalry were well trained and equipped but probably less well mounted than the British. On the other hand, at Waterloo the commander of French forces on the ground was Marshal Ney and he was a cavalrymen through and through, happy to lead cavalry assaults from the front.

The conditions at Waterloo were not favourable for cavalry. The heavy rain had left the ground muddy. The British were at the top of a slight rise which, given the condition of the ground, substantially slowed any cavalry charge. The lower ground between the two armies was very muddy indeed. From a 21st-century viewpoint it is not that difficult to understand that the mud slows the attack, but what is more easily forgotten is that it tires the horses. Very muddy conditions may slow a tank assault, but the tanks will not tire. They may advance slowly, but they will continue to advance for ever. Not so with horses. As the day wore on, horses became more and more tired and less and less effective.

Given the conditions, the role of cavalry was always likely to be limited but they were made even less useful because both the French and the British failed to deploy them properly.

In the assaults on Hougoumont and La Haye-Sante the French infantry was regularly repulsed and cavalry was ordered into support. Cavalry is almost totally ineffective against buildings, and so it proved to be in both these cases. Cavalrymen were lost for no reason whatsoever.

The French cavalry charge against British squares

As the afternoon wore on without the infantry making significant progress against the British line, Ney decided to launch an assault with his cavalry. Forty squadrons (more than 8,000 mounts) rode directly to the British lines, taking substantial casualties from Allied artillery but continuing until they reached the British positions. At this stage all the Allied battalions formed squares, front ranks kneeling, bayonets fixed, with the men in the second rank ready to fire.

It is almost impossible for cavalry to be effective against a well-disciplined infantry square which does not break, unless it is closely supported by infantry or artillery, which Ney was not. The result was that the French cavalry circled the Allied squares, apparently in control of the ground but utterly unable to do anything to exploit this. Indeed, the continual fire from the infantry meant the cavalry was constantly taking casualties, while they were unable to inflict any damage at all on their enemy.

“Round and round these impenetrable masses the French horsemen rode, individuals closing here and there upon the bayonets, and cutting at the men. But not a square was broken; and a body of cavalry which, had it been wisely handled, might have come up at the close of day to good purpose, suffered, ere the proper time for using it had arrived, virtual annihilation.”

Gleig

Why Ney, who was no great strategist but still an experienced soldier, led this charge without infantry support is one of the mysteries of Waterloo. With close infantry support he may have been able to break squares and inflict a decisive blow on the allies, but he didn’t and the day was lost.

A memorial marking the site (more or less) of Ney’s attack

A memorial marking the site (more or less) of Ney’s attack

On several occasions in the afternoon Ney did ask Napoleon for infantry reinforcements and was told there were no reserves he could spare, so it’s possible that he used the cavalry without close infantry support simply because he did not have enough infantry available. It doesn’t really explain the waste of good cavalrymen, though. An alternative explanation is that some of the British troops were withdrawing in good order and this was mistaken for a retreat. At this point, doctrine would suggest that cavalry should be used to pursue the fleeing enemy. As the British formed squares, it became obvious that they weren’t fleeing at all, but by then the cavalry was committed to the charge. This does not seem an entirely adequate explanation. Ney was charging through artillery and as soon as it became clear that, far from fleeing in disorder, the enemy was forming squares, the obvious thing would have been to retreat without further loss. Instead, not only was the attack carried through, but it was continued for some time, even after must been clear that nothing was being achieved by it.

The Scots Greys

The British, too, threw their cavalry away for no good reason. The famous charge of the Scots Greys made a good painting, but achieved little, if any strategic effect.

‘Scotland forever!’ by Lady Butler. It was painted in 1881. Lady Butler had never been present on a battlefield

In the fighting around La Haye-Sante a Highland regiment had advanced somewhat over-enthusiastically and found itself facing annihilation at the hands of a much stronger French force. At this point the cavalry was used in its proper role of providing support to a regiment which was about to be overwhelmed by the enemy.

The Scots Greys moved forward at a walk (the ground was too uneven for the gallop shown in the picture) and passed through the Highlanders who rallied as the cavalry arrived. The cavalry now fell on the French infantry who had no time to form square.

“In vain our poor fellows stood up and stretched out their arms; they could not reach far enough to bayonet these cavalrymen mounted on powerful horses, and the few shots fired in chaotic melee were just as fatal to our own men as to the English. And so we found ourselves defenceless against a relentless enemy who, in the intoxication of battle, sabred even our drummers and fifers without mercy.”

Captain Duthilt of the 45th quoted by Grehan

The Greys should have been satisfied with their success and returned to the Allied lines, but having destroyed the 45th Regiment, they pressed on down the slope. Pausing only to harass another French regiment that formed up and successfully resisted them, they rode on until they reached the French artillery. However, they were not carrying the equipment needed to put the guns out of action, so they contented themselves with killing the gun crews.

“Then we got among the guns, and we had our revenge. Such slaughtering! We sabred the gunners, lamed the horses, and cut their traces and harness.”

Sgt Major Dickson, Scots Greys

Then, tired and disorganised they milled around uncertain of where to go next.

They were now in the thick mud of the plain between the two armies where their heavy horses, blown after their charge, were struggling to move beyond a walk. At this point a brigade of French lancers arrived on the field. The lancers, being lighter and fresh to the fight, were able to move much more quickly across the muddy ground and they fell on the Scots Greys without mercy.

Allied cavalry reinforcements were sent to cover the retreat of the Greys, including a brigade of Belgian-Dutch cavalry. Although British authors claim that they “attempted nothing more than a mere display upon the crest of the position” other accounts suggest that it was the entry of the despised Belgians into the fight that saved the Scots Greys.

The charge of the Scots Greys did massive damage to the 45th and saved the bacon of the Highlanders. By drawing French forces away from the farmhouse, it’s likely that the cavalry charge helped the men in La Haye-Sante hold on a little longer – maybe as much as two hours, which could have had a critical effect on the outcome of the battle. But the cost was enormous and largely pointless because the gains were made before the cavalry over-ran their objective and failed (despite being recalled) to turn back to their own lines. The Union Brigade (Royals, Scots Greys and Inniskillings) suffered approximately 600 dead and wounded out of 1,000 men, (including its commander, William Ponsonby). Looking at just the Scots Greys, of 24 officers who took part in the charge, 16 were killed or wounded.

References

Rev G R Gleig (1875) Story of the Battle of Waterloo

Grehan (2015): Voices from the Past: Waterloo 1815

The header picture is ‘The Charge of the Scots Greys’ by Stanley Berkeley

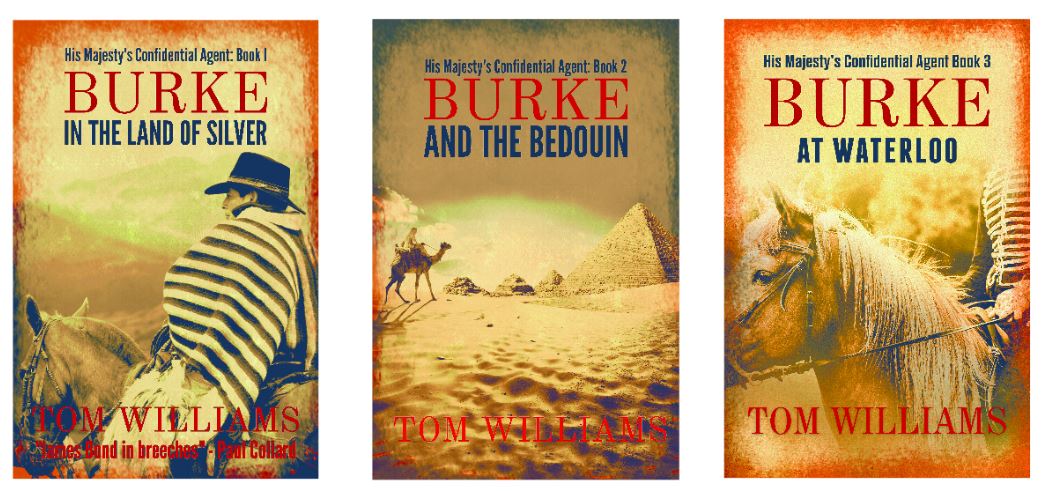

A Word from our Sponsor

Waterloo will be one of many subjects covered at the Malvern Festival of Military History where I will be one of the speakers on panel about writing stories based around actual military events – like my books about James Burke.

I hope some of you will make it to Malvern. For more details go to https://www.enlightenmentevents.com/

by TCW | Aug 3, 2018 | Napoleonic history

Time to return to Waterloo, I think.

We’ve looked at Hougoumont, but now it’s time to turn our attention to Wellington’s other forward outpost – the farm at La Haye-Sainte – that’s the building more or less in the centre of the photo, which was taken from the Lion’s Mound..

Unlike Hougoumont, the farm really was a forward outpost. About three hundred yards in front of Wellington’s centre, the farm, with its substantial farmyard held around 400 troops of the King’s German Legion (KGL), supported by British riflemen who took up position in a pit nearby.

There was surprisingly little action centred on the farmhouse in the first hours of battle with neither commander apparently properly appreciating its importance. As the day went on, though, the amount of fighting around La Haye-Sainte grew.

In Burke at Waterloo, Burke’s sergeant, William Brown, is fighting alongside the riflemen, and the account accords well with real accounts of the battle for the farm.

At last the drummers started to beat amongst the ranks of blue-uniformed warriors and the columns began to bear down on La Haye Sainte. They advanced at a quick step with loud cries of ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ From the heights behind William came a murderous artillery fire that struck down dozens of the advancing soldiers, but they came on regardless.

Now they had reached the beginning of the slope. As they approached La Haye Sainte, skirmishers broke out from the head of each of the columns. Finally, the 95th had something to shoot at. The sound of their rifles was almost lost in the din of artillery as French and British guns duelled across the battlefield.

The farm ahead of them was now the scene of desperate fighting. The French had the place surrounded on three sides, pouring fire into the farmyard. A French brigade moved towards the north of the farm to complete its encirclement. As they did so, they came within range of the sandpit and the Rifles opened up on them. William fired, reloaded and fired again. There was no careful wrapping of the balls now. He rammed home his ammunition as fast as he could. With the enemy so close, it was speed, not accuracy, that was needed. There were so many that it seemed almost impossible not to hit them. The French dropped by the score, but as fast as the men of the 95th killed them, more blue-coated figures moved to replace the dead. Outnumbered as they were, it could only be a matter of time before the Rifles were overrun.

Then, to William’s amazement, the brigade swung away, as if unwilling to face the men in the sandpit. If they were trying to escape the Green Jackets, though, this manoeuvre went horribly wrong, for their change in direction took them straight towards the company that were hidden in the hedge. Once again, their ranks were decimated by British rifle fire.

For a moment, William thought that their three companies of Rifles might achieve the impossible and beat back the French brigade, but, even as the French hesitated, an outburst of firing and cheers drew everyone’s attention to the east. There, through the chaos of smoke, he could see men in the dark blue of the Belgian infantry breaking back towards the main Allied lines while the lighter blue of the French pursued them.

Their captain saw it too, cursed, briefly but fluently, and then turned to his sergeant. ‘The Belgians have broken. We’re too exposed. We have to withdraw.’

William already had his rifle at his shoulder, so he pulled the trigger and took down one more Frenchman. Then, with the rest of the men of the 95th, he started heading back to their own lines.

It was shortly after the French attack described here that the British cavalry advanced in the famous ‘Charge of the Scots Greys’. That cavalry charge in reality achieved very little, but it did relieve pressure on La Haye-Sainte, which held out until around 6.00pm. The King’s German Legion were reinforced by English troops who had become separated from their comrades in the chaos of the battle. The KGL, though, used a different calibre of ball from other units of the British Army and, isolated ahead of the line and unable to use the ammunition of British troops who broke through to them, the KGL was finally forced to withdraw because of a shortage of ammunition.

The French now controlled a strong point from which they could mount a direct assault on the centre of the British line. Such an attack earlier in the day would have been decisive, but Napoleon had left it too late. Blucher’s troops were already on the field and the battle was lost.

Although the farm had been the site of violent conflict for hours, it seems to have survived remarkably intact. The building is now privately owned and still operates as a farm, discouraging visitors. It’s one of the few places on the Waterloo battlefield which does not seem to want to exploit its connection with the events of that day.

A Word from our Sponsor

You’ve just seen an extract from Burke at Waterloo. The book does climax at the battle, but it’s far from a regular military history story, like Sharpe. Burke (a real person, though his adventures here are fictional) was a spy and spends most of the book trying to track down the man who organised an attempt on Wellington’s life while he was the British ambassador in Paris. (Yes, at least one such attempt took place but it was hushed up then and seems to have been hushed up ever since.) There are dastardly deeds, beautiful women, and, yes, there is the battle of Waterloo. What’s not to like?

Burke at Waterloo is available on Amazon as an e-book or now in paperback. North American readers can buy it through Simon & Schuster.

Print of William Frye’s painting of Waterloo after the battle

Print of William Frye’s painting of Waterloo after the battle The farmyard at Mount Saint Jean as it is today

The farmyard at Mount Saint Jean as it is today

Bone saw displayed at National Army Museum

Bone saw displayed at National Army Museum

Standard of the 105th (National Army Museum)

Standard of the 105th (National Army Museum)

A memorial marking the site (more or less) of Ney’s attack

A memorial marking the site (more or less) of Ney’s attack