It’s been a while since I have posted anything about tango, but somebody has asked me to re-post something I wrote years ago about dancing in social settings. It’s not about the dance itself, but about the social rules, the código as the Argentinians call them. I’ll be taking a quick tour of tango around the world, so it may interest non-dancers. If you think it’s not for you, normal service will be resumed on Friday.

As the tango dancers I know are getting excited about venturing out and once again tangoing with friends, we all have to remember how we went about the whole social side of getting a dance. Perhaps that’s why this topic has suddenly become something we are talking about again.

I have danced in London, Buenos Aires, Reykjavik, Paris, Lisbon, Cluj (Romania) and Istanbul, which may seem like a lot of places to non-dancers, but makes me considerably less well-travelled than serious aficionados. Everything that I say is based on that limited experience. In the end, it’s just my opinion, but what you have to remember is that the same goes for everyone else. I do get irritated by people who say that they know the only ‘correct’ way to behave at a milonga (a social dance). The right way to behave is how most other people behave and, if in doubt, in the way that will give most people a pleasant evening. For example, I’ve seen film of milongas in Finland where electronic signs say that men should ask women for this dance and, a little later, that women should ask men. As far as I know, that system is unique to Finland, but if I ever dance in Helsinki, that’s the system I will use.

Let me transport you to Buenos Aires a few years ago. (Places change, so the clubs may no longer be as I describe them.) It’s afternoon in a great barn of a place called the Nuevo Salon. The largely elderly clientele are dancing a traditional tanda – four dances one after the other. The music ends and couples leave the floor, returning to their tables. As the music for the interval (the cortina) plays, men rise to their feet and cross to women who stand to meet them. The next tango starts and, apparently approving of the music, more men stand and, as if by magic, their chosen partners rise to greet them.

How, in this huge hall, have the hundreds of men and women managed to sort out who is going to dance with whom? That is the magic of the cabeceo.

The cabeceo is the look that a man casts towards a woman to show that he would like to dance with her. The woman returns the look and the man approaches her. As he does so, she rises to her feet, he extends his hand and the couple take to the floor. It’s exotic and romantic and Europeans often insist that it’s the only way to invite a woman to dance.

Unfortunately, this simple view of the cabeceo is wrong in almost every particular. For a start, men (wise men who know the rules) don’t randomly cabeceo any woman they would like to dance with. They look for women who appear interested in dancing and, in Buenos Aires at least, the woman will signify her interest with the mirada (literally ‘glance’). This is a meeting of eyes, brief enough to be plausibly denied but bold enough to make it clear that a cabeceo would be favourably received.

The mirada/cabeceo duet can be enormous fun. I’m standing there, running my eyes along the followers sat (or, in London, more often stood) beside the floor and I catch a tiny flash of interest from a stranger’s face. I stop and return my gaze to her. There is a half-smile, the faintest flicker of an eye-brow and I walk toward her, extend my hand and there we are, no words spoken, holding each other as we dance. It is one of the smoothest and sexiest of social exchanges that doesn’t involve actual sex. If that’s how you expect to get your dances in London, though, you’ll spend a lot of time standing around waiting to strike lucky, for few women in London even know what a mirada is, let alone use it routinely. This, on its own, makes the cabeceo far from ideally suited to the London tango scene.

Back in the Nuevo Salon the men are offering their cabeceos and, if they read the signs correctly, they are being accepted. Here’s the second problem. Remember that in London the woman accepted with some tiny acknowledgement of the offer. But when I tried this in one famous Buenos Aires venue I was met with blank looks. Eventually a kind lady explained the rules. In this venue women did not acknowledge the cabeceo with anything so forward as even the tiniest of smiles. Rather they would glance away and then return your glance to check that you were still looking at them. That was it. Otherwise they would just keep their expression neutral with a look uncomfortably similar to that you would get if a woman was “blanking” you in London.

Mirada noted, cabeceo delivered and invitation accepted, you might think nothing else could go wrong. You’d be mistaken. More than once I have walked towards the woman I have invited and, milliseconds before she gets to her feet, the woman sitting directly behind her stands up. I’ve met some good dancers that way, but dealing with the embarrassment of the moment can be more than a trifle awkward.

Based on my experience, those enthusiasts who say that the cabeceo is simple and avoids misunderstandings and embarrassment have either been very lucky or have spent their lives dancing in a limited number of venues with lots of partners they know well. Of course the cabeceo works smoothly if leader and follower know each other. My wife and I can catch the shortest of glances across a crowded room and know that we want to dance together. But the whole point of the cabeceo is that it should allow you to dance with strangers. As I said earlier, when this works, it works really well. In some venues, it is normal not to ask your partner’s name. You meet as strangers, dance as intimates and part as strangers. I love it when this happens, but life is seldom as simple as that.

The legend of the mystical Argentine cabeceo has given rise to all sorts of stories that I can tell you from my own experience are just rubbish. Argentine women will not actively solicit dances, they say: one woman used to look out for me and half rise from her chair, smiling at me as the cortina started. The legend says that Argentinians will never offer a verbal invitation: not only has my wife been invited by men simply asking her, but I remember a woman approaching us as we sat together and asking Tammy if she could borrow her husband. The way that people invite each other varies from milonga to milonga: there is no straightforwardly ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ approach.

In the most rigidly formal milongas, men and women are seated by a hostess on opposite sides of the room. Experienced dancers, known to the hostess, will be sat at the front, next to the floor. Visiting gringos are likely to be in the corner at the back. You know as soon as you are seated exactly where you are in the pecking order. (I was once given a bad seat by a hostess I didn’t know and I smiled sweetly and said I thought there’d been a mistake. I was promptly promoted.) You will stay in the same seat all night. If you are a regular, you will be given the same seat whenever you arrive. Thus everyone knows where you are and women know in which direction to make their miradas. Similarly, you know where the women you want to cabeceo are going to be sitting. It’s a system that works well if you are familiar with the club and the etiquette. If you are a stranger, sat on your own in a poor seat surrounded by people you don’t know, it can make for a really miserable experience. It’s worth trying it once, in a spirit of anthropological enquiry, but it’s not for everyone.

The system requires a seat for everybody at the dance. In Argentina, clubs will always sacrifice floor space to fit in more tables and seating. During the cortinas the floor clears, so men and women have an uninterrupted view of each other. The lighting is good so that people can easily see the expressions of those sitting across the room. In these conditions, with everyone knowing the rules, the cabeceo can work quite well. Contrast the situation in London. There aren’t enough seats, so people constantly move as they are forced to play musical chairs. Men and women are mixed together – fine for conversation, but tricky if you want to catch the eye of someone sat three seats to the side of you. Because there aren’t enough chairs, the floor never entirely clears, so you can’t see the people opposite you. The women don’t mirada and, because they think they look sexier without their glasses, many of them can’t see your cabeceo anyway. (I wish I was making this up, but I’m not.) Plus, in London, dim lighting is the norm, so even if you have got your glasses on, seeing anybody’s expression is tricky. Under these circumstances, relying exclusively on the cabeceo is really rather silly. That’s even before you look at the cultural differences.

In Spanish South America women’s social behaviour was strictly curtailed. A woman could not simply enter into conversation with a strange man. The cabeceo allowed men and women to agree to dance (and only to dance – they return to their separate seats) without breaking social taboos on talking to strangers. Yes, things are different nowadays – but that’s where the cabeceo started. In England, though, the free mingling of the sexes has a longer social pedigree. If you want to ask someone to dance, you can do just that. It’s true that you risk rejection – but a cabeceo can be rejected too (and the rejection is just as public even if slightly subtler). But the rejection of a verbal invitation can be tempered. (I’m told that “I’m sorry, my feet are tired,” is the socially approved phrase.) Confusion is, in any case, much more easily avoided.

I’m not making a special case for the British here. My first evening in Reykjavik every cabeceo I offered was ignored. I had just decided that the women were seriously unfriendly when an Icelander explained that Icelandic women will only respond to verbal invitations. “Go over and ask them,” she said. “They want to dance and are wondering why you are ignoring them.” So I braced myself, walked across the floor and asked a total stranger to dance. And she said, “Yes,” and she was lovely and I was able to enjoy the rest of my time on the Iceland tango scene.

So what does my experience tell me? It tells me that the rules are different in different places. They vary from club to club and city to city. Watch what others do and try to follow them. If you are new to a place and people offer advice, take it. Beyond that, do what works. Look for eye contact and, if you get any, then respond positively. Smile a lot. (I don’t speak Spanish, Icelandic or Turkish. I really smile a lot.) If you can’t make eye contact, talk to people. If there’s a language barrier, smile more. If you think you are embarrassing people, back off. Otherwise, do whatever works. You have come to dance. They have come to dance.

“You dancin’?”

“You asking?”

Game on.

A tango fantasy

During the past year opportunities to dance tango have been (to put it mildly) limited. I spent some of the time I should have been dancing writing a fantasy novel with a lot of tango in it. Most of my books are historical fiction, so a story about vampires in London was something different. My vampires are not your usual creatures of the night: they are (mostly) sophisticated and urbane and they are very, very fond of tango.

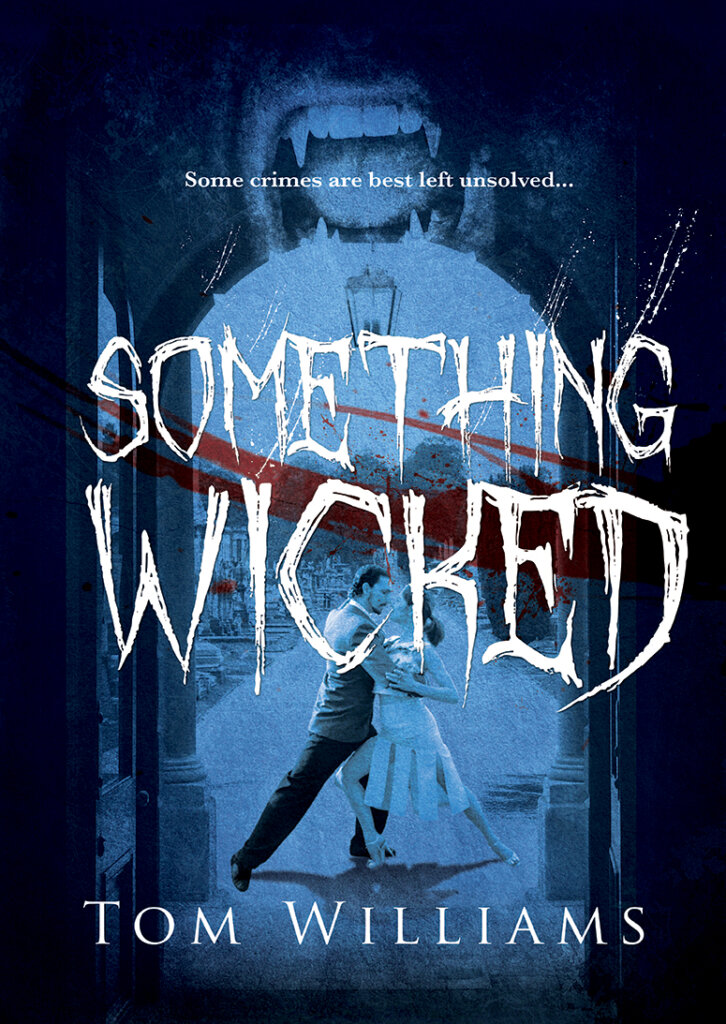

Something Wicked has been described as “a cleverly-conceived, well-written and excellently plotted novel about murder, policing, vampires, and Tango”. It was certainly fun to write and I hope you find it fun to read. You can buy it on Amazon in paperback (£5.99) or on Kindle (£2.99).

London readers may recognise Alexandra Wood and Guillermo Torrens on the cover.

More tango on my blog

If you are new to tango and have enjoyed this, you might like to read this post about why I spend so much of my time dancing – and why you should too: https://tomwilliamsauthor.co.uk/tango/