Last week somebody asked me what it was about Cawnpore that made me want to write about it. Cawnpore was originally published over ten years ago so that’s a long time to think back.

I remember quite vividly what it was that first triggered my interest in the events of 1857 in India. I was spending a long weekend in an isolated cottage in Wales with no TV, Internet, or phone. It was raining. There were bookcases full of books (the place was owned by an English teacher). With nothing better to do, I picked one out more or less at random: Red Year by Michael Edwardes, which describes the events of what he calls ‘the Indian Rebellion’.

I am old enough to have covered what we were taught to call the Indian Mutiny when I was at school. But Red Year described a history I was completely unfamiliar with. There were more books about 1857 on the shelves and as the rain continued (it so often does in Wales) I read several of them.

What happened in 1857 was the culmination of a century of colonialist policies in India. A Marxist could hold it up as a clear example of how the tide of history is determined by economic forces. There was a sort of inevitability to the conflict. There was no inevitability to the outcome, though. The British came a great deal closer to losing India than people nowadays seem to realise.

Although the overall conflict represented a clash of civilisations and economic forces, within this wider conflict individuals and personal loyalties played an enormously important role. The story of 1857 is often a very human story.

There were heroes and villains on both sides, and the people of India often chose the side they would fight for based on personal or family loyalty to local leaders. It was a time of larger than life figures, whose personal strengths and weaknesses shaped the course of history in India for the next hundred years.

I had written the first of the John Williamson stories, The White Rajah, as a single novel, with no idea of producing a sequel. But when the tiny American publisher who had taken a chance on the book, suggested that they would like to publish another one, I realised that the events of the first novel had left my narrator, John Williamson, in Singapore with just time to take a ship to India ready to plunge into the events that led to what he would definitely have called the Indian Mutiny.

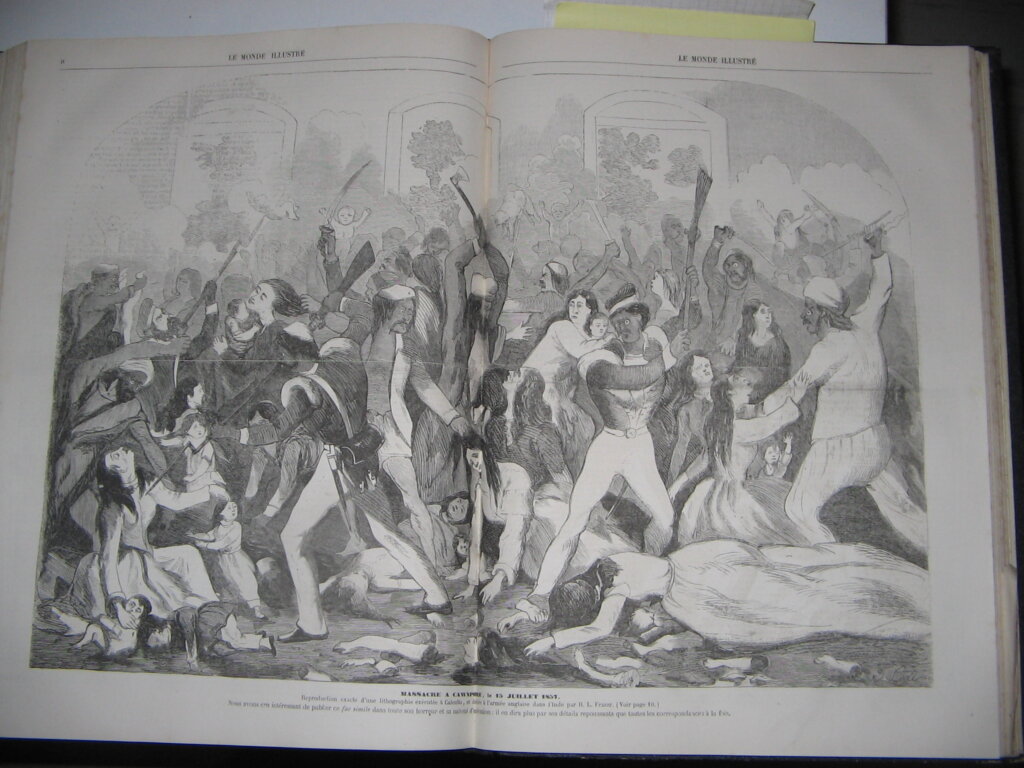

Of all the incidents in 1857, the massacre at Cawnpore was one of the most dramatic. Its horror became a byword for savagery across the world. More interestingly, from the point of view of a writer, it highlighted the confusions and mixed loyalties that had led to the Mutiny in the first place.

It was also particularly well documented. One of the few survivors, Mowbray Thomson, published an account (The Story of Cawnpore) which gives a strong feeling of what it was like to be there. There are also first person accounts from two of the less well known survivors, Jonah Shepherd and Amy Horne. Reading the experiences of people like that is invaluable for a novelist who wants to get into the mindset of his characters.

Working out the details of the plot took some time. They had to fit what we know happened at Cawnpore and what we understand about the leading actors in that tragedy. At the same time, they had to allow the narrator to travel between the British and Indian lines and communicate with both sides. Fortunately there is a wonderful modern book detailing all the events of Cawnpore, Our Bones are Scattered by Andrew Ward. That proved invaluable in allowing me to put together a story that stitches fact and fiction. Most of the detail in the story is accurate and, unlikely as it is, John Williamson’s tale is not at all impossible.

John Williamson is the ideal person to tell this story. As a homosexual, in the days when sodomy was “the sin that dare not speak its name,” he was always an outsider to the rigid English society that characterised the stations of the East India Company. His experiences in Borneo meant he had a natural sympathy with the natives and had become adept at learning their languages. Thus, Williamson allows us to see the events at Cawnpore from both sides of the conflict.

Once I had the plot, I found the writing much easier than in The White Rajah. By now, Williamson was a well-established and fully rounded character in my head and this time his lover was another fictional character, so that I was not continually constrained by what history tells us about him. I found myself carried along with Williamson’s enthusiasm for the country he was working in and then caught up in his horror as he realised how badly things were going to end.

Cawnpore is not a cheerful book, nor does it end with simple rights and wrongs. The story of colonialism, whether that of the British in the 19th century or the new Great Powers of the 21st is neither pretty nor straightforward. The joy of fiction is that it allows us to look at these issues from a different angle, free of the prejudices that we have about the world we are in today.

I can more or less guarantee that Cawnpore will, at some point or other, make you cry. But it’s also a love story which, like every love story, has moments of humour and beauty. And it takes you back to an impossibly romantic world of rajahs and holy men and beggars; a world where a general could still lead his army into war on an elephant, where cavalrymen were dashing and heroic figures, and where a few hundred men, women and children held out against thousands of enemy troops in one of history’s most desperate sieges.

Thank you! With all the talk of 1857 it is often easy to forget the human side of it. It was as you say, “Although the overall conflict represented a clash of civilisations and economic forces, within this wider conflict individuals and personal loyalties played an enormously important role. The story of 1857 is often a very human story.

There were heroes and villains on both sides, and the people of India often chose the side they would fight for based on personal or family loyalty to local leaders. It was a time of larger than life figures, whose personal strengths and weaknesses shaped the course of history in India for the next hundred years.”

Cawnpore is one of those hauntingly uncomfortable episodes of an already violent conflict, full of what ifs and why didn’t they which cannot be answered with any satisfaction. I read your book, if I may admit, three times over and each time, have found it moving.

There is one other account of the siege of Cawnpore – a letter written by one of the survivors, Private Murphy, available in the Wellcome collection https://wellcomecollection.org/works/v5wqjdd5 which I have transcribed on my site – it is always hard to read about Cawnpore and Murphy’s account, written as it is, in raw language, makes it suddenly feel very real. Maybe you might find it interesting?

Thank you!

Thank you so much for this.

I’d never seen Private Murphy’s letter before and it is fascinating. He recounts a terrifying ordeal very matter-of-factly. Thank you for drawing it to my attention.

I am delighted that you enjoyed the book so much. Do you mind if I quote your comment? I have very few reviews (a lot of them were lost when I got my rights back so I could self-publish) and anything positive that has been said about it — especially by people like you with your expertise on the subject — can help it sell. I am always sad that the books about James Burke sell so much better. They are fun to read but I tried to do more than just entertain with ‘Cawnpore’ and it has never had the success of the lighter spy stories.

Of course!! Please do. I hope Cawnpore gets the recognition it deserves!