The trouble with anniversaries is that they come round every year. I’ve been threatening to spend less of my time writing blog posts so as we, yet again, mark the anniversary of the British invasion of Buenos Aires, I’m recycling one from last year. (I’ve edited it a bit though.) The invasion featured a prominent role for Sir Home Popham, who is the subject of a biography that Jacqueline Reiter, one of my fellow-authors in Tales of Empire, has just finished writing. She’s a brilliant researcher and a great writer, so I hope we’ll revisit Popham soon once her book is out. (Who knows? I might even be able to persuade her to write something here.)

It would be nice if Jacqueline’s new book were to generate more interest in the invasion, as most people are unaware of it.

British forces captured Buenos Aires on 27 June 1806. It’s one of the least well-known campaigns of the Napoleonic Wars but the first of the James Burke books, Burke in the Land of Silver, centres on the run-up to this battle (not that there was really a battle) and its aftermath (which was much more exciting).

Why did Argentina matter?

The British invasion of Buenos Aires is often overlooked, possibly because it does not reflect particularly well on British military prowess. Spain’s South American possessions were important primarily because of the silver that they produced. Britain was anxious that, with Spain about to join the war on Napoleon’s side, the French should not get their hands on South American bullion. South America was also felt to be a relatively soft target, because of the unrest amongst the population there who were growing increasingly unhappy with Spanish rule.

Enter Sir Home Popham

Enter the extraordinary Commodore Home Popham. Almost forgotten until recently, Popham has suddenly become fashionable with both historians and novelists, and keeps on popping up all over the place. He deserves this newfound interest because Sir Home Riggs Popham was an extraordinary character.

Popham was a naval officer: his rank kept slipping about depending on whether or not he was politically in favour and on the effectiveness of his efforts at self-promotion. He had been sent to the Cape of Good Hope with a squadron carrying 6,000 men to capture the place, but the Cape fell unexpectedly easily, leaving him with a small army and no war to use it in. At this point, he decided that he’d head to Buenos Aires, taking 1,635 men with him (the rest being left to garrison the Cape). Deprived of a change for glory in South Africa, he would find it in South America. They sound pretty much the same, so why not?

Historians still argue about whether this decision was politically sanctioned or not. It was certainly never official, but there’s quite a lot of evidence that the government did encourage him to attack Buenos Aires.

Enter James Burke

Either way, Popham arrived in the River Plate in June 1806, where he sails into the story of Burke in the Land of Silver. The Plate is a difficult river to navigate. Popham was quoted at the time as saying, “It was a bit bumpy,” as his ships nearly grounded on sandbanks. According to some accounts Popham was helped to navigate the unfamiliar river by a British agent. If so, it’s quite likely that the real James Burke was involved. Was he really? The joy of writing about a secret agent is that what exactly he did do is a secret. He may genuinely have been there, but we can’t know for sure.

Popham was in charge of the force while it was on the water, but once it landed control was handed over to Colonel William Beresford. The illegitimate son of the 2nd Earl of Tyrone, Beresford had served under Wellington and was held by many (though not Wellington himself) to have a less than perfect grasp of military strategy. (He features in Burke and the Lines of Torres Vedras too. If you read that, you’ll know that I’m not a fan.) He landed his troops at Quilmes, fifteen miles from Buenos Aires. The Spanish did not have enough troops to mount an adequate defence and, as Popham had predicted, Beresford had an easy march, brushing aside the meagre forces sent to oppose him. On the 27 June 1806, Buenos Aires surrendered.

Things end badly

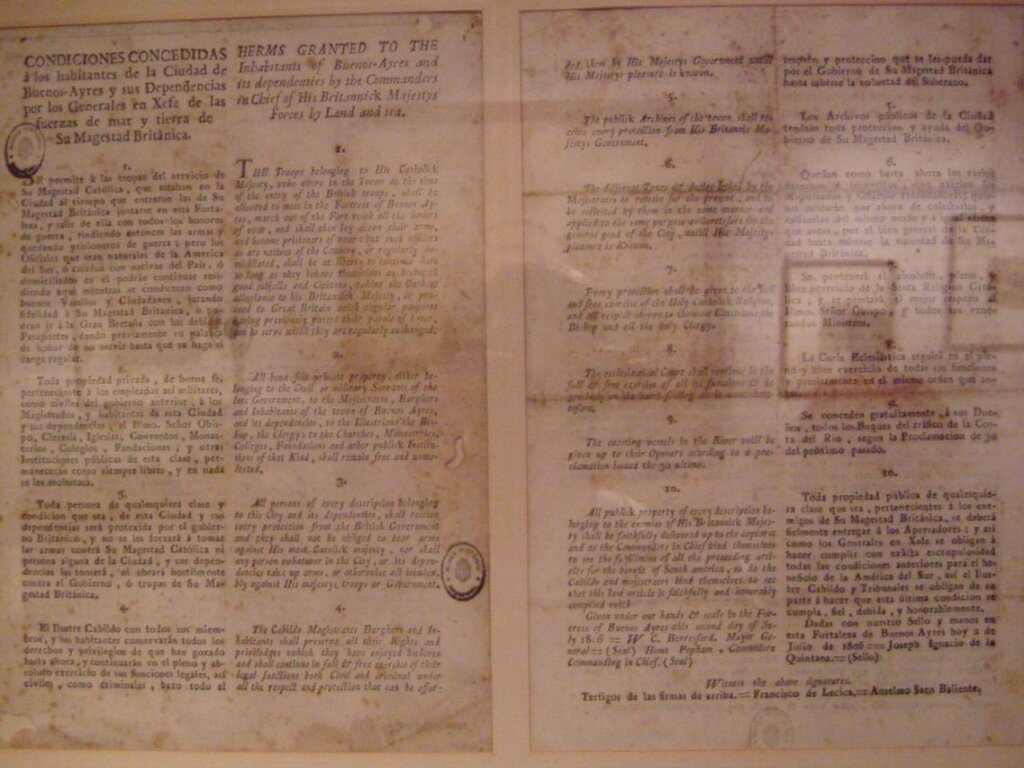

James Burke had arrived in Buenos Aires with instructions to prepare the way for a British invasion. He could congratulate himself on a job well done. But with the military victory easily achieved, Beresford had to move from winning the war to winning the peace. He told the locals he had come to liberate them from Spain and made promises of generous treatment of the city.

In the end, though, he proved no better at handling the aftermath of war than some more modern occupying powers. The confiscation of the State treasury suggested to many people that the invasion was little more than a pirate raid and restrictions on trade with Spain threatened to bankrupt the economy. A series of missteps turned the population against the British and the locals rose in revolt. The British were driven out of Buenos Aires, their tails between their legs.

Aftermath

With the Spanish rising against the French, Napoleon never did get his hands on that silver. The Spanish colonists became our allies again. James Burke did return to Argentina where I like to think he contributed to the struggle of the locals to free themselves from Spanish rule. Whether he did or not, the population did rise against Spain and the independence of Argentina was declared on July 9, 1816 by the Congress of Tucumán.

Nobody is quite sure what happened to James Burke after his ventures in South America, but evidence from the Army rolls suggests that he remained in the Army with a pattern of movement between regiments and ranks that suggested continued to work in intelligence until well after the war with France was over.

Burke in the Land of Silver

Burke in the Land of Silver is the first of the stories I’ve written about James Burke. All my stories have a solid basis in historical fact, but this one is the closest to a true story. Burke’s adventures, including his improbable romantic entanglements with royalty, are pretty close to what actually happened. The story grew out of my love for Buenos Aires and I have visited many of the places featured in the book. It’s a rollicking good read, as well as an excellent introduction to a little-known bit of Britain’s military and political history. It’s available on Kindle at £2.99 (buy it quickly: this price won’t hold forever) and in paperback at £7.99.

Picture credit

‘The Glorious Conquest of Buenos Ayres by the British Forces, 27th June 1806’ Coloured woodcut, published by G Thompson, 1806. Copyright National Army Museum and reproduced with permission.