This is a sequel to The Assassins and you really ought to read that book first.

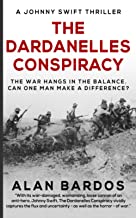

There is quite a lot happens in The Dardanelles Conspiracy, all of it based on the historical facts that led up to the horror of the Gallipoli landings. If, like me, you are vaguely aware of that campaign but have never been quite sure how it came about, then this book will give you a lot of context. It falls into two parts, the first about the doomed attempts to bribe Turkey to allow the passage of the Dardanelles without the British having to take military action, and the second a description of the opening of the campaign when the negotiations fail. The failure, according to this book, was pretty well inevitable as the British did not negotiate in good faith.

The details of opaque diplomatic negotiations are, inevitably, on the dry side. What kept me reading (and, I imagine, anyone else who loved The Assassins) was following the continuing escapades of Johnny Swift, the anti-hero of Bardos’s previous book. Johnny continues to duck and dive, a cad and a bounder but someone we somehow want to win through, whether he is collaborating with the enemy, faking illness to extend his sick leave or seducing his superior’s wives. Several of the people from the first book also make welcome returns alongside some wonderful new fictional characters – in particular a couple of German officers whose almost constant drunkenness conceals a strong commitment to their military duty.

There is a good cast of non-fictional figures too. A young Churchill reminds us that Winston was a terrible military leader in World War I, though fortunately rather better a quarter of a century later. I never knew he had a brother in the Dardanelles and Jack Churchill was just one of the interesting historical figures to pass through the story.

Once we move to the actual assault on the Turkish positions, there is nothing dry at all about the story-telling. Bardos gives a good outline of how the battle started. It’s clear how much of British strategy was based on straightforwardly racist contempt for the Turks. A few snowflakes reading Guardian articles on the commitment of Turkish soldiery to defend their homeland could have saved an awful lot of British lives. ANZAC lives too, though Bardos makes little mention of them. He would be well advised not to agree to any book tours in Australia where the sacrifice of “colonial” troops at Gallipoli remains a source of bitterness to this day.

Bardos catches the horror and the chaos of this sort of warfare really well: the chaos, perhaps, rather too well. The initial plan of attack was insanely complicated (the sort of thing that a junior officer nowadays would be taught could never survive contact with the enemy). Without a map the reader will struggle to keep track of the relative positions of the troops on Beaches V, X and Z, let alone the strategic importance of Hill 138 or Hill 114. Mind you, the reader’s confusion will reflect that of the men on the ground. The commanders, safe offshore in their battleships, did have maps but, with no efficient means of communication, they lost direction of their forces. The result was a bloodbath and Bardos captures that very well.

The book takes a very Reithian approach to combining fact and fiction. (Like Reith’s BBC, it entertains, educates and informs.) If The Dardanelles Conspiracy doesn’t combine fact and fiction as seamlessly as The Assassins, that reflects just how good The Assassins was. If you enjoyed The Assassins, you will enjoy the further adventures of Johnny Swift and Bardos’s insights into a campaign which is too easily forgotten about in Britain.