The last (probably) of my posts inspired by the conference on “War and Peace in the Age of Napoleon” is a revival of a post that first appeared here in July last year. It’s about the fight for Hougoumont, virtually a battle within the larger battle of Waterloo. The first clash of troops in the battle took place at Hougoumont and fighting continued there right up until the French army broke at the end of the day. It is widely regarded as one of the most important strategic points of the battle with Wellington claiming that its defence was crucial to his success.

Hougoumont was the subject of Charles Esdaile’s presentation at the conference. Charles enjoys attacking peoples’ established ideas – he’s practically the definition of a “revisionist historian” – and he argued that Hougoumont, far from being the key to the battle, was a practically irrelevant sideshow. I can’t resist reposting my original piece on Hougoumont that made much the same argument more than a year ago.

If you want to see a very short video of the place that I made when I visited (before writing the article) it’s at https://youtu.be/V_LT31i1fjY

Hougoumont

Although Hougoumont lay some way ahead of the main British lines, it was not occupied as an advance position. It was seen as part of Wellington’s overall defensive strategy, protecting the west of his line or, as Wellington put it in his dispatch, because it “covered the return of that flank”.

Prior to the battle, Wellington had been convinced that Napoleon would swing round to the west, threatening the British supply lines that ran through to Ostend. So concerned was he that he left a substantial force to guard the supply lines against the attack that never came, reducing the number of men available to him at Waterloo. Wellington’s conviction that Napoleon would attempt to attack his right flank seems to have influenced the decision to occupy Hougoumont. It wasn’t a stupid idea: Napoleon often used flanking movements in battle. In this case, though, Wellington seems to attach more importance to Hougoumont than could really be justified. The British right was, as Wellington’s dispatch said, “thrown back to a ravine”, which already offered substantial protection. [Charles Esdaile pointed out that Wellington had also covered that flank with a considerable amount of artillery.] Also, there was quite a lot of woodland in that area and this would have impeded the advance of blocks of infantry moving in formation, as was required to engage effectively in early 19th century military conflicts. Not for nothing do we talk about “the field of battle”. Armies needed large open spaces to manoeuvre, so flanking attack on the West was unlikely to be a particular danger.

Nonetheless, Wellington had four companies of the Brigade of Guards occupy the chateau (probably around 400 men).

Hougoument was a substantial building – or, more realistically – complex of buildings. The photo below shows the farm as it is today and gives you some idea of the size of the place.

When the Guards arrived at Hougoumont (driving out a few French who they found exploring the place) it was dominated by the fortified castle, with a small tower, that stood in the centre of the complex, adjoining the chapel (the small white building that still stands there).

The photo above is taken from what were then formal gardens, beyond which was an orchard. From the point of view of the soldiers defending the place, the important thing is that this land was surrounded by a brick wall, which still stands.

During the night before the battle, the British troops did what they could to improve the defences. Loopholes were made in the walls and fire steps constructed. Charles Esdaile points out that there may well have been loopholes there already, as Hougoumont had featured in the War of the First Coalition in 1794, but the Coldstream Guards are supposed to have been ordered to make loopholes and I suspect they would have done so even if something remained from another battle 20 years earlier. Guards regiments are like that – they reckon soldiering done by other regiments is automatically inferior.

Since 1815 much of the wall has fallen down and been rebuilt and the “loopholes” we see today are 20th (or 21st) century additions designed to appeal to the increasing number of visitors to the site.

Loopholes in the garden walls.

One gate – the northern gate that was closest to the British lines – was left open, but the others were barricaded shut.

Between Hougoumont and the French lines there was a wood and there was concern that this could provide cover should the French attack. Early in the morning, about a thousand German troops were sent to reinforce the defenders, many of them taking up their positions in the wood and the orchard within the farm walls.

Although the troops were stood to from dawn, for hours nothing happened while Napoleon positioned his men. Not all of the French forces were ready by late morning, but Napoleon decided that he needed to start an attack. When, rather late in the morning, Napoleon finally opened his attack, he did not drive toward the British centre, but ordered an assault on Hougoumont.

The French assault was led by Napoleon’s brother, Jerome, who attacked with five and a half thousand men. The attack was almost certainly a feint, designed to draw Wellington’s forces from the centre to defend his right flank while Napoleon prepared his main assault.

The result should have been a foregone conclusion and, indeed, the French succeeded in driving the German troops out of the wood, but they then had to attack across the strip of open land to get to the garden wall. This area was well covered by British musket fire through the loopholes, while the French for unable to return any effective fire against soldiers in a well protected position.

[Since I wrote this, there has been new work done at Hougoumont tracing the location of all the musket balls in the area. This suggests that the French followed a path through the wood in their initial attack, which meant that they were bunched quite tightly together. This was probably a significant element in the failure of the assault. Had they advanced through the wood in skirmish order, they might have succeeded.]

What had started as a diversionary attack had now gained a momentum of its own. Frustrated by his inability to take the place defended by such a relatively small force, Jerome Bonaparte threw more and more troops into the fight, which became a separate conflict – effectively a battle within the wider battle of Waterloo.

Eventually the French forces took possession of the wood and of the orchard, but the British still held the farm buildings – two courtyards with the substantial Gardener’s House, a great barn, the chapel and, of course, the chateau itself.

The Gardener’s House

Despite their repeated efforts, the French were unable to enter the farm complex. They came under fire from the loopholes in the walls, from the windows of the houses and even from the roofs where British soldiers had stationed themselves to fire down on the enemy below.

French losses were terrible. The plaque below marks the point at which a French general died at the foot of the garden wall, very close to one of the main entrances the courtyard.

Closing the gates at Hougoumont

The north gate remained unbarricaded, allowing the evacuation of wounded troops towards the Allied lines. The fighting continued outside the farm too, and troops retreating from the French would use the north gate to gain the cover of the farm buildings when they were driven back. Eventually a small French force swung round past the worst of the fighting and attacked the farm from the north. They are supposed to have been led by one Sous Lieutenant Legros, known as L’Enfonceur, or ‘the smasher’ on account of his size and strength. It’s likely that this man was more myth than history, especially as he was supposed to have fought at La Haye Sainte as well. Certainly, though, some brave Frenchman did manage to force open the gate. About thirty to forty French troops forced their way into the courtyard and, with the rest of the French force close behind them, it looked as if Hougoumont would fall.

‘Closing the Gates at Hougoumont’ by Robert Gibb (painted 1903)

Ten of the defenders threw themselves against the gates and forced them closed. All the French soldiers who had forced their way into the courtyard were now trapped and every single one of them was killed except, so the story goes, for a drummer boy who was spared.

The incident was presented as crucial to the defence of Hougoumont (which it probably was) and to the outcome of the battle. This is because Wellington remained convinced that the defence of Hougoumont was a central part of his strategy and that its fall would precipitate an Allied defeat. As already noted, this is extremely unlikely. Hougoumont was a diversionary attack that had, by now, grown completely out of control. Nonetheless, the closing of the gates became one of the defining legends of Waterloo, celebrated to this day.

Memorial to the defenders of Hougoumont. The inscription, ‘Closing the Gates on War’

refers to the century of comparative peace in Europe that followed the battle

Even now, the north gate, though barred, was not barricaded, the defenders being anxious to keep their lines of communication with the main Allied force open. By one in the afternoon, the defenders had fought off three large-scale attacks and were running low on ammunition. An officer broke out of Hougoumont and found a Private Joseph Brewster of the Royal Waggon Train in charge of an ammunition cart near the British line. The lane leading to Hougoumont was now under heavy musketry fire from French skirmishers, but the waggon was galloped under enemy fire into Hougoumont, providing the ammunition needed to continue the defence.

The miracle of the chapel

The assault on Hougoumont was unusual for the French, in that it was not supported by artillery. The farm was screened from French artillery by the forest and, although some round shot did strike the buildings, there was little effective use of French artillery during the morning. The British, by contrast, were able to use artillery placed on the ridge to bombard French troops approaching Hougoumont, which was a significant factor in its defence.

In the afternoon the French did succeed in bringing howitzers up within range of the buildings. They started using carcass projectiles (early incendiary shells) and soon both the chateau itself and the great barn were on fire.

Wellington, observing the smoke and flames from the ridge, sent orders that the men were to stand firm.

‘I see that the fire has communicated from the hay stack to the roof of the chateau. You must however still keep your men in those parts to which the fire does not reach. Take care that no men are lost by the falling in of the roof, or floors. After they have fallen in occupy the walls inside of the garden; particularly if it should be possible for the enemy to pass through the embers in the inside of the house’.

The British had put many of their wounded in the shelter of the chateau and the adjacent chapel. Most of those in the chateau died and the flames were spreading to the chapel. There was a crucifix above the door of the chapel and the flames reached the foot of the crucifix, burning one of the legs. At this point the fire died and the chapel still stands. The men who had been sheltering there, too badly wounded to flee through the flames, were saved. It was hailed as a miracle, although a cynic might point out that there was little in the chapel to feed the flames.

The crucifix has been much restored over time, although the head, with its fine carving, remains the original. In 2011 it was stolen and remained missing until 2014 when it was found and restored again. It now hangs back in the spot where watched over the wounded in 1815.

Although all the significant buildings within the farm when now destroyed by fire, the British continued to resist and, despite further waves of French attacks (including one in which a dozen or so French infantrymen actually made it into the courtyard) Hougoumont held on.

Fighting at Hougoumont continued until the general retreat of the French with the arrival of the Prussians and the end of the battle. The Allied force defending Hougoumont, probably never exceeded three thousand troops, with another three thousand in close support, but by their stubborn defence, they exhausted the strength of no less than thirteen thousand French troops.

Did Hougoumont matter?

The importance of Hougoumont in strategic terms was almost certainly overestimated by Wellington. Napoleon had never seen it as a strategically important goal. He had no intention of attacking the British right flank and, in any case, he could simply have outflanked the farm had he really wanted to do so.

Tactically, Hougoumont may well have made a difference. The considerable number of French troops who ended up committed to this “battle within a battle” was not available for the main assaults, where they might have had a significant effect.

Hougoumont’s main importance, though, was in its contribution to the legend of Waterloo – the idea that a vastly outnumbered force of British soldiers was able, by their heroic resistance, to see off Napoleon and the French. This rather plays down the contribution of the Nassau and Hanoverian soldiers who defended the place alongside the British. It did, though, contribute to the myth of British military prowess that allowed Britain to ‘punch above its weight’ for a hundred years and, arguably, longer. Whether this was an entirely goods thing is for the reader to judge.

Sources

An excellent account of the defence of Hougoumont is available on the website of ‘Project Hougoumont’ which was set up initially as part of the project to restore the farm and which now seeks to knowledge of the battle and ongoing research on the history of the Waterloo. The web address is https://projecthougoumont.com

On that site you can find an excellent paper by Alasdair White: “Of Hedges, Myths and Memories : A historical reappraisal of the château/ferme d’Hougoumont, Battlefield of Waterloo, Belgium.” I am grateful to Alasdair for his comments on this article, which were very helpful. It is impossible, in a short piece like this, to provide anything more than an overview of the battle. Anyone wanting more detail could do a lot worse than read Alasdair’s paper which is also available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333683103_Of_Hedges_Myths_and_Memories_A_historical_reappraisal_of_the_chateauferme_d’Hougoumont_Battlefield_of_Waterloo_Belgium

I also benefited hugely from my visit to the farm and from the museum and materials presented there.

A word from our sponsor

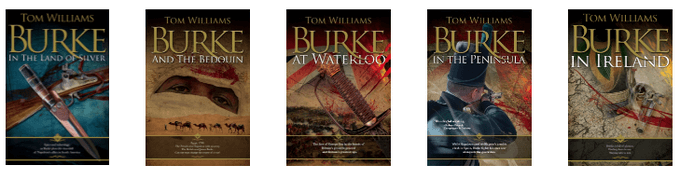

You probably know that I wrote a book where the climax takes place at the battle – Burke at Waterloo. What you may not know is that this is the third book about James Burke. (There are five altogether now with a sixth due out soon.) There was a real James Burke and the first of all the books I have written about him (Burke in the Land of Silver) is very largely based on truth. We know that James Burke continued to work as a spy for the British, but whether he was ever in Egypt (Burke and the Bedouin) is, quite honestly, unlikely. There are one or two unexplained incidents during Napoleon’s invasion which, if Burke was there having the adventures he has in the book, could now be explained.

Burke may well not have been at Waterloo, either, but, as you probably realise, the events taking place around him all really happened as described.

All of the books are available from Amazon on Kindle, all at under £3.00. They are also all published in paperback. If you enjoy reading the blog, it would be very nice if you bought some of the books. You never know – you might enjoy reading them too.