I seem to have been reading a lot of historical fiction lately featuring spunky women heroines who won’t be tied down by the conventions of the period they live in. They talk to men they haven’t been introduced to in the 19th century, they learn to read and write in the 16th century, and they express profoundly liberal opinions on matters like women’s suffrage and take up unlikely professions such as surgery almost whenever.

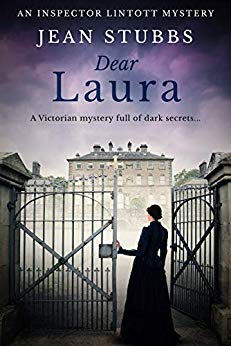

The truth is that life for women in, say, the 19th century could be pretty grim. Dear Laura shows us just how unpleasant it could be, even if you were a middle-class wife with a rich husband living in comfort in late 1890 Wimbledon.

Dear Laura is presented as a detective story, but it’s more a psychological thriller. We hear a lot nowadays about coercive control, as if it were a new thing. What Dear Laura makes terrifyingly clear is that “coercive control” is what many a Victorian paterfamilias would have called “family life”.

Jean Stubbs takes us into a well-off but not ridiculously rich Victorian home. The husband is a brute, who rules his little empire with a coldness bordering on sadism. His sons are sent off to boarding school, his daughter, despised because she is a girl, is left to the not-so-tender mercies of her nurse. Below stairs Cook rules over the alcoholic coachman, the maid and the skivvy, while Kate, the lady’s maid, occupies an ambiguous position between the regular servants and the better class of persons Upstairs. Laura, meanwhile, floats around the house looking beautiful, saying as little as possible and subject to constant headaches. Kept away from her children because her husband thinks she spoils them, she finds love only from her brother-in-law. Titus, her would-be lover, is, in his way, as objectionable as her husband: extravagant, promiscuous, selfish, but – unlike his brother – not actively cruel.

When Laura’s husband dies suddenly and anonymous letters hint at poison, the estimable Inspector Lintott is called to investigate and he uncovers a positive cesspit of secrets and lies that draw in almost everyone in the house.

This is by no means a perfect book. Some things are revealed in uncomfortable flashbacks than can take you out of the moment and leave you wondering what exactly is going on. Occasionally the sub-text of conversations is presented in italic, usually a sign that the characterisation and the dialogue aren’t quite up to carrying the load placed on them. I’m happy to forgive Ms Stubbs these flaws, though, because the book carried me along, anxious to find out the truth about these people – some good, some bad, but all trapped in the bonds of a social system in which “knowing your place” was the key to survival.

Above all, I welcomed a book that showed the truth of many Victorian women’s lives. For anyone who thinks Stubbs’ view is unrealistically bleak, the epigraphs with which she starts her chapters are revealing:

I know nothing like the petty grinding tyranny of a good English family… Florence Nightingale

Home is the girl’s prison and the woman’s workhouse. George Bernard Shaw

As a general rule, a modest woman seldom desires any sexual gratification for herself. She submits to her husband only to please him… William Acton MRCS

The book rings true to its period. Stubbs has done her research and occasionally ladles it in rather over-enthusiastically. On the whole, though, she does not allow details of the price of meat or the numbers dying of influenza to get in the way of her narrative. They are the background of a wider world, but her story dwells in one household and we see how its inhabitants cope with the social order that the wider world forces on them.

In summary, an excellent book and a wonderful antidote to some of the romantic nonsense being written about women living at a time where #MeToo was more #TheWayThingsAre.

Interesting post, and I am not disputing the historicity of it in terms of the period this book is set. However the opening comments re the 16th c particularly deserve some qualification. In the early 1500s Martin Luther advocated education for both boys and girls and actively promoted a ‘public purse’ to pay for it and in Scotland in the late 1500s a school in every parish open to both boys and girls was the ambition of the church. And even prior to this, although girls didn’t get the opportunity to go to college as boys from higher class families did, many were literate, taught either at home or in convent schools. Re medical professions it should also be noted that in the hospital in Florence in the 16th c there were women pharmacists and in the early 1300s a woman is recorded as a prosector – and as having knowledge of anatomy and pathology. (That is one of the people I’m considering as a subject for a novel based once I’ve finished my current project.

Absolutely fair point. I was driven to the comment I made by the number of books I’ve read lately which suggest that life was fine for women in the late 18th and the 19th centuries – the period I know most about. I accept that there were rare cases of women succeeding in male spheres – sometimes even disguising themselves as men to gain acceptance. And, of course, there were women who flouted convention, openly took lovers, chatted to men they hadn’t been introduced to and so on. But they were very much the exception rather than the rule. The problem is that so many of these exceptional women now feature in stories (not just the sort of “historical romance” where the servant girls marries the Duke and where historical accuracy really isn’t the idea) that people are beginning to think that life for women back then was pretty much as it is now. I read one book where I know the author had done a lot of research on the physical reality of the 19th century but she had a modern woman suddenly transported back to being a servant in a 19th century household and she coped perfectly well, despite bringing her 21st century attitudes with her – and this writer is intelligent with a real interest in history. Reading these books you really wonder why women ever bothered with feminism when everything was apparently just fine.

You don’t have to go as far back as the 19th century. I read one book that was presented as a historical novel set in the 1950s where the heroine regularly drank on her own or with a woman friend in a public house. I’ve had older women describe their experiences of pubs in the 1950s and that just wasn’t possible. Women friends tell me it could be uncomfortable even in the 1970s.

There are writers who really do depict the lives of women in a realistic way. Carol McGrath and Deborah Swift both stand out for me, though I know there are many others and you may well be one of them. But there are far too many who don’t.

Very interesting topic, and personally very relevant, since my series spends a lot of time pointing out the ways in which life was not okay for women. However, I think it’s fair to say that as writers, we’re more likely to concentrate on the outliers, because they’re interesting – and they did exist, no question of it. Where it often goes wrong is when a woman does behave in an unconventional way and nobody around her appears to notice it’s weird and there is no comeback on her for doing so. I’ve had a lot of comments around this. One reader complained that I seemed to punish my female characters for behaving independently, as if a woman was asking for trouble by having opinions or stepping outside convention. The answer is sadly, that’s probably true, society often did punish women who did that. Another objected to the fact that my heroine, who was something of a forceful personality, still deferred to her husband too much and didn’t even seem to resent it. And yes – she did. That’s what was seen as a happy marriage in around 1812. And a third got very angry with me because she said it was unrealistic that an intelligent woman would stay in a violent marriage for two years and not tell anybody. As a former counsellor in a woman’s centre, I didn’t even bother to answer that one. I think it’s more interesting to write about an unusual woman, but we need to set her within the context she actually lived in. Personally, I don’t do all that well with time slip or time travel novels because of that, I find myself too distracted by constantly thinking “how is she managing so well, I wouldn’t even know how to get myself dressed in the morning in such a different era”. But that’s just me, I know a lot of people do them very well.

It’s true what you say about outliers. I think that the problem is that everybody writes about the outliers and eventually readers just unconsciously assume that that was the way life was. I have been having rather a run of these. Sometimes it’s just a little too much informality and I really wouldn’t notice except that I just read another book with too much informality and before that there was one with unrealistic attitudes and before that … My personal bugbear (and I’m pretty sure you haven’t done this) is where someone says, “By gad, listening to you I realise how much better things would be if only women had the vote.” I’m sure someone said it once, but I really doubt it came up that often.

But anyway: I didn’t set out to rubbish other writers but to say how much I enjoyed this book. I am sure that some people will say it is unrealistically grim (and bits of it are grim indeed, though the way it’s told means it isn’t a gruesome read) but I just found it a refreshing antidote to some of the rather pollyanna-ish depictions of the place of women I keep coming across elsewhere.