by TCW | Jan 25, 2019 | Indian history

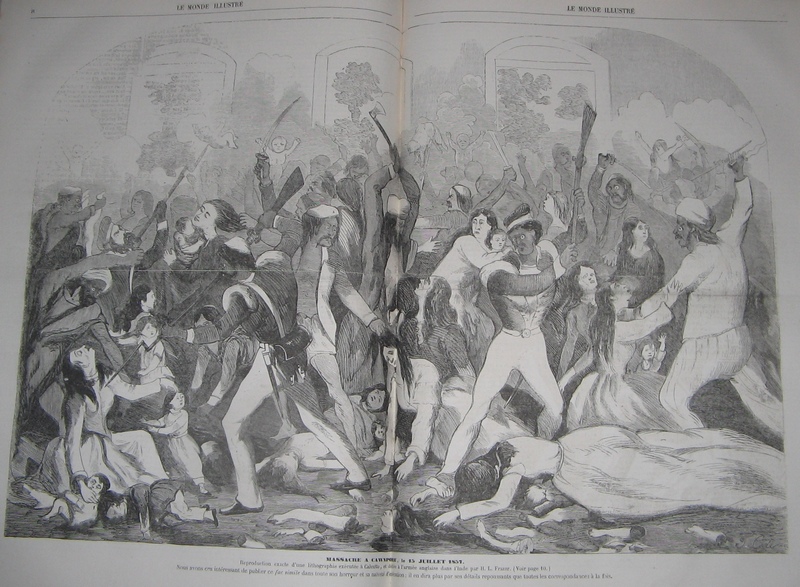

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about Nana Sahib, “the demon of Cawnpore”. I suggested there that the rights and wrongs of his behaviour (and that of the British) were not as straightforward as they are often presented. Even so, when Heather Campbell of The Maiden’s Court invited me to write the story from Nana Sahib’s point of view, it was a serious challenge. After all, how do you set about justifying a war crime?

In the end, I was pleased with what I wrote and I thought I’d like to share it here. I know that a lot of people who read this blog are interested in writing and I do recommend things like this as useful exercises. And for those who don’t write, I hope you can just enjoy it as a different way of looking at an infamous bit of Indian history.

Nana Sahib’s story

My father was the Peshwa of the Maratha Empire. He was a mighty lord who rose against the British who had come into his country and despoiled it. He fought valiantly against the invaders, but he was defeated and exiled from his own country to the miserable little village of Bithur, not far from Cawnpore. The British allowed him to retain his title and a small pension and he made his peace with them and lived alongside his enemy until he died in 1851.

I was an adopted son – a common practice in my country when a great lord has no sons of his own – but the British refused to recognise me as Peshwa and no longer paid the pension that they had paid to my father.

Despite the loss of my lands, my title and my pension, I tried to be a good friend to the British. They had ruled in India now for a hundred years and many Indians had accommodated to them. But their rule was becoming more harsh. Where once they had made honourable peace with men like my father, now they seized their lands, ignored their titles, and denied them the respect they were due in their own country. They began to send Christian missionaries who tried to tempt my people from their faith. They told us we must abandon our old customs.

Those Indians who served in their armies (for there is no disgrace in serving the army of any lord once he has proved himself a power in the land) were not accorded the respect they had been. Their officers, who had once loved this country, were replaced by arrogant fools who did not understand our ways. There were rumours that they might be sent overseas, where they would lose their caste. Then there was the terrible business of the new cartridges. The cartridges were greased with the fat of cattle and with the fat of pigs. This was an insult to all the Hindus in the Army and to their brothers who were Moslems.

Finally, the people of India rose up against these injustices. I was not sure what to do. I had been friends with the British and I hoped that things could be settled without violence, but it was soon apparent that there must be a war and that the British would finally be driven from our country. My people looked to me, for they still called me “Peshwa” and acknowledged me as their leader. Now that it had come to war, it was my duty to lead my people against the British in Cawnpore.

The British fought bravely: I will give them that. Hundreds of my troops died as we attacked their fort again and again. In the end, I agreed to lift the siege if they would go. They said they would and asked for boats to sail down the Ganges to rejoin their people. But this had to be a trick. The British were being defeated everywhere. Where could they hope to go? No, once they were on the boats they could set up a fort somewhere else and attack us from there. My generals told me I would be stupid to let this happen.

What was I to do? They had surrendered, but there was nowhere they could go. We had an army in our midst that could turn on us at any time. The British, we Indians had learned over the past hundred years, were liars. They had promised my father he could keep his title and then took it from me because I was adopted: a cheap trick. They had stolen the Kingdom of Oudh on the same pretence – that the new King was adopted, and therefore could not inherit. We could not trust them.

My general, Tatya Tope, told me what to do. He arranged to have artillery hidden across the river from the boats and for his men to conceal themselves along the banks. When the British came to the boats, we opened fire. They still had their muskets. It was war: these things happen. We tried not to kill the women and children, but we took them captive and kept them safe.

Then news came that a British force was on its way to relieve the siege. Everybody was terrified. The British were killing people who they thought might have ever harmed any of their troops and they would kill us all if they heard what had happened by the river. It was essential that any of the British who might speak against my sad, but necessary, actions should be silenced. I had no choice: the women and children would speak against me. They had to die. So many Indians had died under British rule and the British always said that sometimes these things were necessary or that sometimes these things just happened. But would they have happened if the British had not stolen our country? Had we asked these women and children to come and live amongst us, ordering their Indian servants to do this and to do that as if they were slaves? Bringing their foreign ways, their terrible food, their arrogance and their ignorance? They looked down on us as savages and sneered at our ways. Well, they’re not sneering now.

The British beat us in 1857. I was driven into exile and watched as the white men tightened their grip on my country. But I know that our time will come. It is not right that the Indians should live under the rule of the British and one day we will rise up and we will defeat them and I will not be hated by the rulers of India, but loved by them as one of those who showed the way to regaining our own country.

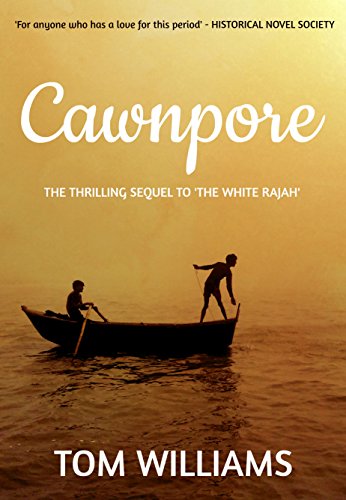

Cawnpore

The story of Cawnpore and the clash of cultures that led to the massacre is the subject of my book, Cawnpore. The narrator is English, but in love with an Indian. Caught between the two camps, he sees the tragedy developing around him, but is powerless to stop it. Can he survive the massacre and, if he does, can he save anyone else from the horror?

Cawnpore is the second of my books about John Williamson but it stands alone. Of the three, it is my personal favourite.

Cawnpore is available on Kindle and in paperback. It has had some lovely reviews.

“All that historical fiction should be: absorbing, believable and educational.” – Terry Tyler in Terry Tyler Book Reviews

“For anyone who has a love for this period, Cawnpore is probably one for you.” Historical Novel Society

If you haven’t already, I do hope you will buy it soon.

by TCW | Jan 22, 2019 | Book review

Imperial Warriors has recently been re-published by Endeavour Media, who are my publishers. I’m interested in the Gurkhas, so I was happy to pick up a free copy of the book. It was intended as a little light reading in military history but I found myself fascinated by the story it tells and what it says about both the Imperial British past and the modern Army. When I sat down to write a review it ended up rather longer than I had intended – part summary, part critique and part essay. It’s probably rather like the book: worth dipping in and out of and reading the bits that interest you. Hopefully some of it will.

Some history

Tony Gould served with the Gurkhas in Malaya (as it then was) during his National Service. Like many British officers, he fell in love with the Gurkhas and extended his service to stay on and fight with them until his career was cut short by polio. This book starts with a personal account of his time in Malaya, which goes some way to explain his fascination with the Gurkhas before it plunges into a history of Nepal and the tribes that made up the kingdom.

The history is complicated and I must confess that I struggled to follow it. The crucial part, as far as the relationship between Britain and the Gurkhas is concerned, is that border disputes between Nepal and land controlled by the East India Company led to an invasion by the British in 1814. Following a British victory in which the Gurkha troops had distinguished themselves by their bravery the peace treaty allowed the British to recruit volunteers from the Gurkha army into the Indian army. (At the time it was not uncommon for troops in India to transfer their loyalty between rulers.)

By April 1815 a battalion of Gurkha troops was in action on behalf of the British. This battalion eventually became the 1st King George’s Own Gurkha Rifles, the first Gurkha troops formally incorporated into the British forces which they serve to this day.

A little bit of old-fashioned racism

Nepal was a country built on conquest and the conquered people retained their own identities (and their own vassal rulers). The first distinction the British made was between the “real Gorkahs” and the conscripts from the conquered territories. When the British first started to recruit Gurkhas into their service they were explicitly forbidden to recruit “real Gorkhas” on the grounds that people from the conquered tribes were likely to be loyal to their new leaders while the “real Gorkhas” would be less reliable.

This distinction between different Gurkha tribes eventually developed into a classificatory approach to the various tribes of Nepal that many nowadays (the book was first published in 1999) would reject as “race science”. Even Gould complains that the British carried this classification process to an extreme and a reader in 2018 might be uncomfortable with some of it but the differences between the various Gurkha tribes does seem to be important to an understanding of Nepalese history and the relationship between the Gurkhas and British. It can still produce some odd passages though, like these views ascribed to Lieutenant-General Sir George MacMunn:

In sum, the tall and fair-skinned people of the North West were martial; the short and dark South Indians were not. But where does that leave the Gurkhas who were neither tall nor particularly fair?

Gurkhas were covered by an aspect of the martial races theory mentioned by MacMunn – the philosophy of climatic difference, the supposed superiority of temperate zone man over tropical man…

The Gurkha’s Highland credentials, along with his evident military ability, then, gave him his ticket of entry to the exclusive martial races club.

It’s important to make it clear that Gould himself criticises this sort of talk, but there is inevitably a lot of it in the book. On the one hand, I share his admiration for the Gurkhas, but I feel uncomfortable with the idea that these soldiers are especially admirable by virtue of the fact that they are Gurkhas. The notion that ascribing positive characteristics to a particular ethnic group is just as racist as associating negative stereotypes with them can easily become “political correctness gone mad” but the recurring image of plucky little brown men performing extraordinary feats of valour and endurance under the strict but kindly supervision of fine upstanding Brits does begin to jar eventually. The Gurkhas are, indeed, Imperial Warriors and can easily elicit the patronisingly superior attitudes of an imperial age.

A dashed good tale

The book suffers, like many military histories, from a superfluity of anecdote, but the anecdotes are so good it is easy to forgive them. Whether it’s the story of Rifleman Lachhiman Gurung, who, in World War II single-handedly defended his position for four hours against repeated Japanese attacks despite having to fire one-handed having lost the use of an arm early in the action, or the career of Brigadier-General W D Villiers-Stuart who commanded 1/5th Royal Gurkha Rifles, the stories are all well-told and the gallantry described is humbling. The anecdotal approach can interrupt the time-line of the book, though. The British Army often seems to exist out of time anyway (a Guards regiment still dresses formally for black-tie dinners every night, apparently unaware that it is 2019) but the approach of this book can lead the reader from the mid-19th to the late-20th century with dizzying and confusing speed. Perhaps this reflects the actual experience of the Gurkhas. On one page they are invading Tibet in 1903 (very much in the 19th century imperialist tradition) and a few pages later they are fighting in the trenches of the First World War. If the abrupt transition is a jolt to the reader, you can only imagine what it must have been like for them. Unprepared, untrained and unequipped for this totally alien form of warfare their experience was horrendous and their reputation for courage and fighting spirit took a serious dent. By 1915, though, they were already getting the hang of this new form of warfare and by May two NCOs had received IDSMs. (It’s significant that their Distinguished Service Medals were prefixed as “Indian” reflecting the modified form of apartheid then common in the Army.)

Between 1914 and 1918 55,000 Nepalese were recruited to the British forces, a level of recruitment that had a significant effect on Nepalese society. More than a tenth (perhaps as many as a fifth) of the 100,000 Gurkhas mobilised during the war were killed, wounded, or missing in action. One commentator wondered if any country directly involved in the war lost such a high proportion of its fighting men.

The move to Indian independence

After the war, the Gurkhas found themselves busy with work which was unpleasant in a different way. The move towards independence in India meant that Gurkhas were used as riot police. They were involved in many disturbing incidents of which the most notable was Amritsar. The Gurkhas were not culpable, for they were acting under orders, but the shooting down of civilians was not something that a professional soldier ever enjoys being involved in.

Indian independence, when it came after World War II (where the Gurkhas distinguished themselves in the Far East) was to bring a crisis for the Gurkhas. The Indian government (many of whose members had previously denounced the Gurkhas as imperial mercenaries) now decided that they would be invaluable addition to the new Indian army. The British conceded the principal that around half of the Gurkhas serving under the British flag should transfer to the Indian Army. The mechanics of the process were not well handled. Gould suggests that Indian agents used underhand means to recruit many Gurkhas who would have preferred to serve in the British Army.

Talks on exactly how the Gurkha forces should be divided ran up against the reality of the timetable of partition and, according to Gould, “administrative convenience triumphed over ‘guiding principle’: choosing British Gurkha regiments on the basis of which battalions were stationed in Burma (and were due to leave the now independent country) was the easy option.” Some of the oldest Gurkha regiments found their allegiance transferred from Britain to India with some of the newest regiments put in their places. To a civilian whether your regiment was founded in 1815 or well into the 20th century might hardly be a relevant factor in deciding on operational deployments, but the Army cares about things like this. The casual casting aside of long established regiments with proud traditions (especially those that included the word “Royal” in their title) caused real distress to soldiers and officers alike. The distress was particularly acute for European officers, many of whom were effectively forced out of the Army as the policy of Indianisation took effect.

The End of Empire

Those Gurkha regiments that had transferred to Britain were, in 1948, designated the Brigade of Gurkhas. Ideally it would have been given time to get used to its new situation, but this was not to be the case. From 1948 to 1966 the Gurkha infantry battalions were almost continually engaged in fighting, first in Malaya and then in Borneo. In those 18 years the Brigade of Gurkhas lost 13 British officers and nearly 200 men. Yet the end of the war was followed immediately by cutbacks which saw many of the men sent back to civilian life in Nepal. Conditions for the returning soldier were unlikely to be good as Lieutenant-Colonel Langlands of 2nd Gurkha Rifles explained.

“For the first few months their children could get dysentry, some dying even before they reached their homes. Their small pension or gratuity would not be sufficient to feed them, so they would have to fight to win their food from the soil, and overcome hail, landslides, floods and fire. A few would invest their gratuity in a share of a taxi or a little shop. There were some who had no land to return to and their future was grim.”

Gould is understandably unimpressed by the behaviour of the Ministry of Defence whose civil servants (and those at the Treasury) he clearly considers responsible.

Paradoxically, though the British could be seen as having behaved very badly the sharp decrease in the number of men recruited to the Brigade of Gurkhas greatly increased competition for these places. The desirability of work with the Gurkhas was increased as Gurkha troops were more often serving in Britain where they were paid additional allowances to bring them into line with the British troops they served alongside.

Gould points out that the increased integration with the British Army meant that “improvements in pay and conditions served only to highlight residual inequalities”. This was the start of a campaign for changes in the pay and residency rights of Gurkhas which stretched well beyond the time this book was first published in 1999. The absence of anything bringing the book up-to-date is a definite weakness. Gould understands, as many commentators failed to, that a significant reason why the British employed Gurkhas since the early 19th century is that they were cheaper than British troops. There is a constant tension between the perfectly proper desire of Gurkhas and their supporters to see them employed on the same terms as British troops and the desire of Nepalese Gurkhas who have yet to join the army to continue to have their Brigade of Gurkhas to employ them.

For Gould the return of Hong Kong to China and with it the move of the Brigade of Gurkhas to Britain marked the end of what he calls “the Gurkha world”. The Gurkhas continue to serve, but it is clear that Gould’s love affair is dying. The Gurkhas he formed such an emotional attachment to were those of the 19th century and the world they lived in still survived in the regiments and customs of the Gurkhas he joined in 1957.

The Ghurkas today

Imperial Warriors is, as the title suggests essentially a history book. The Gurkhas he describes are an almost mythic race. Yet I know an officer who, presented with the job that might well be seen as career ending, was convinced that he still had a future with the Army when he was told that he could serve with Gurkhas. The British Army is built on tradition and regimental ties and as the old county regiments are merged or disbanded the Gurkhas maintain a proud tradition of 200 years of service to the British Crown. Gurkha regiments are remarkably effective infantry and as the Army is increasingly plagued by manpower shortages they are likely to have a role for a long time yet. Issues of pay and the treatment given to them when they retire touch many sensitive nerves: our attitudes to immigration; the economics of maintaining an army the country really can’t afford; and the residual racism of both the Army and the British establishment. Gould is not really interested in these issues. The book ends with him returning to Nepal and elegiac account of the countryside and the men who live there. The book is, indeed, a tribute to a world that has gone. It is, for all its rambling and anecdote, a worthwhile and fascinating read but there is another book to be written about the role of the Gurkhas in the modern army. It may not be as exciting and it will almost certainly be shorter, but it is a tale that deserves to be told.

by TCW | Jan 18, 2019 | Uncategorized

I have a guest post this week from Jemahl Evans, whose Civil War books are great fun. (There’s a review of The Last Roundhead HERE.) Jemahl mixes fact and fiction to great effect and here he writes about d’Artagnan (yes, that d’Artagnan) who really existed before first Dumas and now Evans stole his life for their stories

—————————————————————————————————-

Alexandre Dumas’ musketeer trilogy is a classic of literature. The books have been made into multiple movie and television incarnations since 1903 when The Three Musketeers first hit the silver screen to the BBC’s 2014-16 version: different languages, comic versions, steampunk, silent and talkie, monochrome and colour, even an animated version with dogs taking the characters roles. Anyone who has read my Blandford Candy series will know Dumas musketeers are a massive influence on my writing. My penchant for metafiction means the series already features the real Milady D’Winter (Lucy Hay, Countess of Carlisle, who really did steal the Queen of France’s diamond necklace) as an antagonist, and, with a certain inevitability, my take on the real D’Artagnan and two of his compatriots is in the upcoming third book (Of Blood Exhausted).

The historical D’Artagnan was born near Lupiac, in what was then Gascony, in 1611. His family were petty aristocrats. His grandfather Armand de Batz had been a merchant who had been made a noble of the robe and purchased the family chateau Castlemore ( the chateau still survives today but is in private hands so getting in to see it is pretty much impossible). D’Artangan’s father Bertrand married into the powerful and influential de Montesquiou family who gave young Charles the d’Artagnan title – de Batz de Castlemore, Comte d’Artagnan. It was these family connections that would give the boy his leg up in Bourbon France.

In 1632, Charles’ uncle supported his entry into the army with the help of his old friend Jean-Armand du Peyrer, Comte de Troisville and Captain-Lieutenant of the Black Musketeers (Monsieur Treville in Dumas books). This was far too late for d’Artagnan to have been involved in the theft of Anne of Austria’s jewels or the Duke of Buckingham’s machinations at La Rochelle as Dumas portrayed – Buckingham was assassinated and La Rochelle fell in 1628. Nevertheless, d’Artagnan quickly proved himself an able soldier. By the mid-1630s he had joined the prestigious musketeers and during the early 1640s was involved in the Franco-Spanish theatre of the Thirty Years War. His regiment campaigned in the Spanish Netherlands and Southern France, taking part in sieges at Arras, Colliere and Baupame. The heavily fictionalised account of his life by Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras (Les mémoires de M. d’Artagnan) places him and his companions in England during the Civil War at the first Battle of Newbury (1643) fighting for King Charles I, but there is no firm evidence for this. The King’s musketeers were disbanded in 1646, but it is clear that by then d’Artagnan had come to the attention of Cardinal Mazarin and was being employed as a spy. The deaths of Louis XIII and the infamous Cardinal Richelieu in early 1643 had created a crisis in the French government. Louis XIV was only a child and opposition to Royal government was extreme. Cardinal Mazarin became de-facto ruler of France (and allegedly the lover of widowed Queen Anne). Desperate to avoid a civil war or revolution in France, Mazarin used d’Artagnan and his friends as agents throughout the 1640s and 50s (yes, there really was a Porthos, Aramis and Athos too, although Athos was killed in a duel in 1643).

By 1648, the situation in France was almost as dire as England. A series of revolts against royal power known as The Fronde broke out, and d’Artagnan was constantly on the move for Mazarin even when the cardinal was officially in exile, although just exactly what he was doing is never really clear. By 1652, a semblance of order had been restored and Louis XIV had reached his majority. D’Artagnan was promoted to Lieutenant of the Gardes Francais in 1652 and made captain of the regiment in 1655. Throughout the 1650s he led his troops against the Spanish as the Franco-Spanish War dragged on and on. When Louis XIV reformed the King’s Musketeers in 1657, d’Artagnan was made a second lieutenant; a veritable promotion because of the prestige of the unit.

Mazarin’s death in 1661 again created a power vacuum in French government. One of the contenders for chief minister was Nicolas Fouquet, a finance minister who had amassed a vast fortune from his position whilst the French state was virtually bankrupt. Fouquet’s dreams of power were dashed by Louis XIV asserting his personal control, and appointing Jean-Baptiste Colbert as Finance minister to reorganise taxation. Fouquet was manoeuvred into selling his rank in expectation of further promotion and thus temporarily losing his privileges and official protections. Louis arranged for d’Artagnan to arrest Fouquet after a session of the royal council. Fouquet, by all accounts, left the meeting in good spirits after being flattered by the 22 year old Sun King only to find the musketeer waiting.

Again, Dumas used the background of Fouquet’s arrest, the Fronde, and the mystery of the Man in the Iron Mask (yes there really was a man in a mask too) to create his sequels to The Three Musketeers. Dumas makes the mysterious man a brother of King Louis and Fouquet a hero of the tale. In reality, Fouquet was tried, convicted, and imprisoned for the rest of his life. The identity of the Man in the Iron Mask is unclear, but some evidence points to an individual named Eustace Dauger rather than a royal brother. D’Artagnan meanwhile was well rewarded for his royal service. He was made Captain-Lieutenant of the King’s Musketeers in 1667, taking the rank of his first patron Troisville, and subsequently governor of Lisle. It was not a happy appointment. The old musketeer was an unpopular administrator, and petitioned to return to the field rather than stay in the desk job. He got his wish and was recalled to the colours when the Franco-Dutch War broke out in 1672, but was killed at the siege of Maastricht when a musket ball hit him in the throat.

Just like Dumas and de Sandras, I have gone back to the real history to create my portrayal of Mazarin’s spy whilst also paying homage to their earlier creations. And, I have to confess, used Richard Lester’s version of d’Artagnan and Roy Kinnear’s Planchet.

Excerpt

Here’s a sneak peak of d’Artagnan in his third book Of Blood Exhausted.

Monsieur D’Artagnan and his servant Planchet seemed to do little more than drink, revel and feast at the Tabard. They were waiting on orders from Mazarin, so they said. Personally, I found it irritating, but the news of a sword exhibition at least piqued the Frenchman’s interest. I met with him in the backroom overlooking the river, and took Figgis along to keep him out of my sister’s way. The table in front of D’Artagnan was piled high with different dishes of food and a pitcher of wine, and he lounged in a chair with one leg over the arm as Planchet poured the sack. St John had agreed to pay the Frenchmen’s tavern bill, and they were making good use of the account.

‘An exhibition of swordplay?’ said D’Artagnan. ‘Finally something to break the boredom of this godless city.’

I started to laugh; ‘godless city’ was a phrase William Everard used often enough, but I wagered the radical puritan poacher meant it for completely different reasons to a papist French spy.

‘Pourquoi riez-vous de moi?’ said the Comte. (Why are you laughing at me?)

‘London is greatest city in the world,’ says I, proud of my adopted home.

‘Mon Dieu, Candy! For a city to be great, Monsieur, the food and wine needs to be glorious, the people engaging, the conversation stimulating and the women enchanting. London has none of this. Come to France; you will find good food, better wine than this piss, and prettier girls in every village.’

‘Pas Gascogne, maître,’ said Planchet. ‘Les Gascons sentent mauvais.’ (Not Gascony, master. Gascons smell bad)

‘Silence, Planchet,’ said D’Artagnan. ‘Planchet is from Paris. Even the poorest Parisian thinks himself better than a Gascon comte, even when that comte is his master.’

‘Surtout quand le comte est son maître.’ (Especially when the comte is his master)

Planchet grinned at Figgis. The blackguard clearly understood the English tongue. He was more than the comte’s mere servant, I was certain. My rustic valet opened his chops as if to say something.

‘Ye know…,’Figgis began.

‘I have similar problems with witless and impudent servants,’ I said, glaring at Figgis to be silent. ‘And what be wrong with the wine and food? You seem to have enough of it.’

‘Ah the wine: it is Spanish, sweet, sickly and thick, at best. The good wine is never sent here. Instead it is barrels of poor quality vinegar, that you quaff and quaff, caring nothing for taste or body. You cannot even pour it properly, always right to the brim to get as much as possible in your cup.’

‘Ils doivent être très assoiffés, maître.’ (They must be very thirsty, master.)

‘And the vegetables, you murder the vegetables. There is a reason God put the English on an island: it is to stop you poisoning the rest of us.’

‘What be the matter with the vegetables?’ I liked pottage.

‘There are farms nearby. I picked a leek, fresh and crisp and full of taste. You English turn it into this.’ He pointed to the dish of pottage on the table. ‘You boil the flavour out of the food. I would rather eat rat meat; C’est dégoutant.’ (It’s disgusting)

‘You ate a raw leek? That be disgusting.’

‘And what is the jelly? Aspic? You put a boiled egg in aspic then choke it in spice: ginger, nutmeg, and cardamom; tres dégoûtant!’ (very disgusting). And then you encase it in a pastry so tough it could be made of stone. Pastry should crumble and melt like butter on the tongue.’ He sat straight in his chair and pointed to some salted fish cooked in cider and honey; another dish I was partial to. ‘You live by a river yet there is no fresh fish anywhere in the city, it seems. Why is that? Salted fish, spiced fish, smoked fish, dried fish, and pickled fish, but no fresh fish at all?’

‘Well, you would not wish to eat ought that came out the Thames near London,’ I told him. ‘The poisson is liable to be poison. You are supposed to be seeking out an Imperial assassin, not on a culinary tour of England.’

D’Artagnan, waved his hand dismissively at me. ‘Believe me, Monsieur Candy, nobody would come to England on a culinary tour. The ravaillac runs out of the most precious commodity,’ he said. ‘Time for him is pressing. Perhaps your theatre event will be the place he next chooses to strike.’

‘Why think you?’ I did not want anything to spoil our grand design.

‘If the Prince can be killed before the spring it will sow confusion and discord in the alliance, and here in England. By May, France will be invading the Hapsburg Empire, and your new Parliament army will face King Charles. Ferdinand is losing the war; thousands were lost in a battle in Brandenburg last November.’ He picked up a chicken leg, bit into it and spat it out again. ‘Quelle surprise, even the bird is dry and overdone. The only thing you English can cook is roast beef.’

Planchet started to chuckle.

‘Stop whining about the food,’ I snapped. ‘Dip it in the bread sauce if ’tis too dry.’

‘Je ne recommanderais pas la sauce, maître,’ said Planchet. (I would not recommend the sauce, master)

by TCW | Jan 15, 2019 | Book review

I recently came across an old blog post by Deborah Swift on “Subtlety and Melodrama in Historical Fiction”. She explains that melodrama can slip in when the action becomes too fast paced. With historical novels one solution that she suggests is to “remind myself of the reality of the world I’m writing about”. It is the research, and the context in which the drama happens, that roots the story in reality and prevents the melodrama from getting out of hand.

It’s an approach that is very clear in The Gilded Lily. Ella and her younger sister Sadie have fled Westmoreland where Ella has robbed her dead master. (How involved was she in the death? It’s not at all clear.) They make their way to London where they soon discover that the money they have stolen is hardly enough to keep them. Their dreams of living as fine ladies meet the reality of life for young women in the mid-17th century city.

Deborah Swift certainly follows her own advice to root herself in the reality of the world that she is writing about. The book accurately reflects the dreariness and misery of life for the working classes of the time. The sisters first find work in a wig factory, their fingers constantly cut as they pull the threads through the hessian of the wigs, their necks and arms stung as their overseer lashes at them if she sees them lift their heads from their work. It’s an excellent historical account, but the drab monotony of their lives can’t help but rub off on the reader. Despite interludes of excitement when they think that their crime in Westmorland might be catching up with them, it can (despite Swift’s easy writing style) be a long and sometimes difficult read.

Eventually Ella, the more daring of the two, finds work with the distinctly suspect Jay Whitgift, the son of a successful pawnbroker. Ella has hopes of winning Jay’s heart and hence finally escaping from the drudgery of daily life and becoming a respectable woman. It is a measure of Swift’s skill in summoning up the period that we never for a moment think that she will succeed. Other novelists may give us girls who marry rich men and live happily ever after, but Swift is too firmly rooted in the reality of the 17th century to let us believe for a moment that this will not end badly.

It ends extremely badly indeed. True to the approach that she outlined in the blog post, Swift uses the solid historical background of the story to allow her to leap off into something that, without such careful preparation, could easily be completely over- the-top melodrama. Instead, I was gripped as a story of two poor girls making their way in the city turned into a tale of white slavery, murder, arson and a dramatic finale at the Frost Fair held on the frozen Thames. Suddenly I was turning the pages enthusiastically wanting to know if Ella could escape Jay’s murderous plan or if Sadie was indeed condemned to starve, literally locked in a garret.

The Gilded Lily offers an outrageously exciting story in a beautifully detailed period setting. If the beginning seems a little worthy, it’s well worth sticking with.

Recommended.

by TCW | Jan 11, 2019 | Indian history

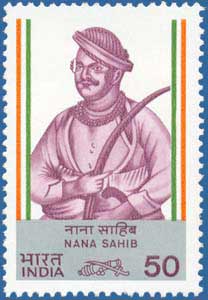

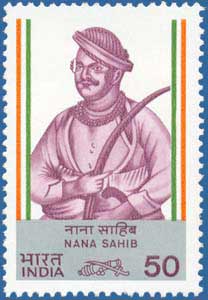

Just before Christmas I had a request from Lydia from Toronto (sounds like I’m writing a problem page). She asked for more posts about the people who were caught up in the historical events I describe. Given the interest there’s been in the item about Indian history that I just revived from my old blog-site (you were fun, Blogger, but life moves on) I suggested I might dig out something I wrote about Nana Sahib, one of the key characters in the siege of Cawnpore, as featured in my book, Cawnpore. Lydia was happy with that, and fortunately I’ve come across some more details of the end of his life since my original post, so here goes:

‘Real’ historians tell stories pretty much as much as historical novelists do and, when I was young, the story that was told about Cawnpore had a clear villain: Nana Sahib.

Nana Sahib was, according to the Victorians (and it is their version of the Mutiny that dominated the way it was seen for a hundred years), the evil genius of Cawnpore. He was the local Indian prince who pretended sympathy for the British, and then betrayed them. Most importantly, he was the man who ordered the massacre there. For decades, he was hunted by the British, who wanted to drag him before their courts and, after a show trial, execute him. But he vanished after the British recaptured Cawnpore. For decades, there were claimed sightings of the man, but eventually it was presumed that he was dead and, in time, the historical character was forgotten and only the pantomime villain of Cawnpore lived on.

I believe that Nana Sahib was a much more complex and sympathetic character than he is usually painted, and I have tried to reflect this in my book.

Seereek Dhoondoo Punth was born in 1824 into an undistinguished family, but was adopted by Baji Rao, the Peshwa of the Maratha Empire. His capital was at Poona (now Pune), which was one of the main political centres of India. From there, he ruled over the most important of the Indian kingdoms.

The Maratha Empire was riven by internal strife and some factions went to war against the British. There were three wars in total and, after the third, the British decided to annex the Maratha Empire. Baji Rao was allowed to keep his title and even given a pension by the British. However, he was stripped of all political power and forced into exile. He chose to live in Bithur (now Bithoor), a small town near Cawnpore (now Kanpur).

Baji Rao needed a male heir to succeed him and, in the absence of a natural heir, Nana Sahib was adopted in 1827 and raised to inherit his father’s position. This was a common practice in India when a ruler did not have a male heir. The British, however, refused to acknowledge that an adopted son could inherit a hereditary title and would not acknowledge him as Peshwa. By then, the title was purely honorary and it is possible that the British did not realise how much distress this caused, although Nana Sahib petitioned repeatedly for his title to be recognised. He also petitioned that the pension that was paid to his father should continue to be paid to his father’s heirs, but the British refused to do this, claiming that the pension had been personal to Baji Rao and their obligation had died with him.

Nana Sahib toyed with the idea of travelling to England to appeal directly to the East India Company but, as a Brahmin, he would have lost caste by travelling overseas. He therefore sent Azimullah Khan, one of his most trusted advisers. Azimullah Khan appears to have enjoyed his trip, especially as he was something of a ladies’ man and was a great success with many of the women he met in London. However, he was completely unsuccessful in pleading Nana Sahib’s cause and the experience seems to have left him with a very strong antipathy for the British.

Despite Azimullah Khan’s attitude to the British and Nana Sahib’s grievances against them, the Peshwa enjoyed the company of Europeans and was very fond of entertaining them, occasionally arranging parties in the European style at his palace, Saturday House, at Bithur. His generosity made him a popular figure with the English who saw him as a useful friend. He was particularly trusted by Charles Hillersdon, the Collector (senior British official) at Cawnpore. When the Indian Mutiny broke out, Hillersdon asked Nana Sahib for military assistance. The Nana’s troops moved into the town to guard the Treasury.

At this stage, it seems likely that Nana Sahib had not decided which side to ally himself with. Many of his advisers, especially Azimullah Khan, urged him to act decisively against the occupiers, and regain his rights and titles through military power, but he was unwilling to commit himself while the outcome of any war seemed in doubt. In any case, it seems likely that he had genuinely warm feelings for Hillersdon and some of the other British officials. On the other hand, he was proud of his Indian heritage and his position as Peshwa – a position the British were still refusing to acknowledge.

After considerable vacillation, he threw in his lot with the rebels. Some people believe that he was forced to do so. The fact was, though, that the troops of his already in the town made resistance futile and, in any light, his action had to be regarded as a betrayal.

The British evacuated town and took shelter in a hastily constructed entrenchment on the outskirts. Despite the impossibility of their position, they held out against Indian attack for almost three weeks, when they were offered safe passage in return for their surrender. Their commander, General Wheeler, considered that surrender was an honourable option, given the almost certain death of the women and children in the Entrenchment were the siege to continue.

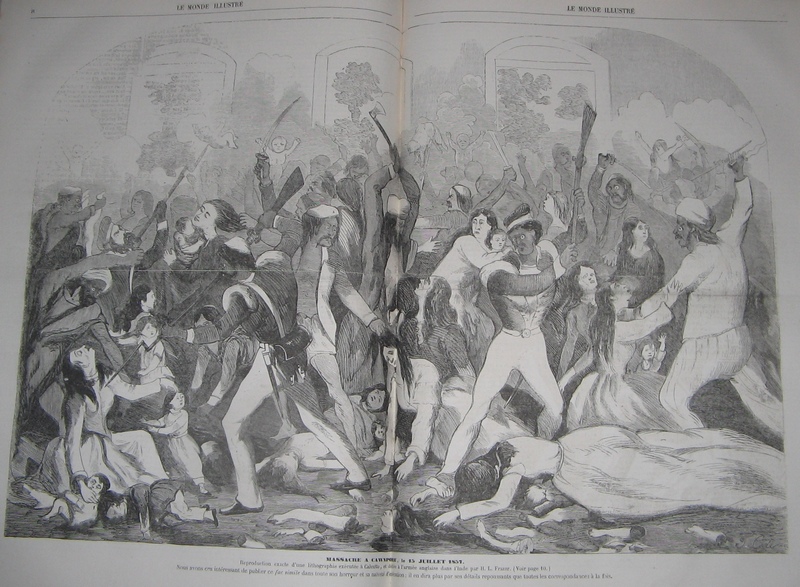

The Indians agreed that the British should evacuate Cawnpore by water. The British therefore marched out of the camp to the nearby river, where a small fleet of boats was waiting for them. However, as the British started to board the boats, the Indians opened fire. Only four of the soldiers from the garrison escaped alive.

Once the British had surrendered, it seems likely that Nana Sahib was pressured to agree to massacre them in order to prove that he was firmly on the side of the native population and that he would not be able to turn against them if (as happened) the British returned to Cawnpore in force.

The initial attack on the British after their surrender left many of the women and children alive and in Nana Sahib’s hands. Again, he seemed uncertain what action to take. He did not kill his captives and, although their conditions were not good, he seems to have done his best to provide them with reasonable food and shelter. To the extent that they were ill-treated, this seems to have been largely due to the attitudes of some of the people who were dealing with them on a day-to-day basis, while Nana Sahib kept his distance. Eventually, though, the decision was made to massacre the women and children. At the time, the English straightforwardly blamed this on Nana Sahib, but there is no record of who actually ordered the massacre. Many people think the decision was taken by Azimullah Khan. Nana Sahib himself refused to witness the massacre.

After Cawnpore was once again firmly in British hands, Nana Sahib disappeared. He was said to be hiding out in Nepal. Margaret Oldfield, the wife of the British Residency doctor there, wrote that the Resident “has not the slightest doubt that these monsters are alive” in Nepal. The matter was a diplomatic problem as Britain was anxious to maintain friendly relations with Nepal and the Nepalese government was unwilling to hand over a Brahman to face certain death. The situation was resolved by concocting a story of the death of the Nana. Nobody believed it, but it suited both governments to accept the fiction and Nana Sahib was left in peace. Although he was widely believed to have died there by 1906, a report in the The Hindu (a major Indian newspaper) in 1953 claimed that he had moved back to India. There, they said, he lived out his life little more than a hundred miles from Cawnpore, finally dying in 1926 at the age of hundred and two.

Cawnpore

Cawnpore is the second book in my John Williamson trilogy, although it can be enjoyed without reading the first. (If you want to read all three books, this is probably a good time to mention that they are now available as a Kindle bundle.) After his adventures in Borneo (The White Rajah), Williamson takes a job with the East India Company at Cawnpore. After his time with James Brooke, the relationship between the rulers and ruled in India comes as a shock, but he finds a friend at the court of the Nana Sahib. When rebellion breaks out, he is caught between his loyalty to the European community and his friendship in the Indian court. As the tensions between the two communities move toward atrocity and counter-atrocity, can he be true to his friends and keep both them and himself alive?

Cawnpore is not a particularly easy book to read (lots of people have told me it has them in tears) but this story of a decent man caught up in the horror of colonial war is one I am particularly proud of. At the time, my son was serving with the British Army in Afghanistan. The issues that were so obvious in 1857 are still there today and I am grateful to have had the chance to write about them.

Cawnpore is available on Kindle and as a paperback. It can also be bought through Simon & Schuster and Amazon in North America. Note that the cover may be different in North America.