by TCW | Jun 28, 2019 | Uncategorized

After all the excitement of Waterloo, this week marks the anniversary of another British victory – albeit one that was rapidly followed by an ignominious defeat.

On 27 June 1806, Buenos Aires surrendered to British forces under Sir William Beresford. The British saw Buenos Aires almost as a target of opportunity. They had sent over 6,000 men to the Cape of Good Hope under Commodore Popham, but when the Cape fell unexpectedly easily Popham thought it would be a good idea to attack Buenos Aires. Buenos Aires was Spanish and we were at war with Spain, so it was a perfectly acceptable idea. A rapid conquest seemed possible because he believed, correctly, that the locals were unhappy with their colonial status and unlikely to resist the British effectively. Popham, whose views on cost-effective warfare had a lot in common with those of Donald Rumsfeld, was enthused by the prospect of plunder from the silver-rich province. Popham may have had official authorisation for his plan from the British government, but this was officially denied. There was no trans-Atlantic cable to send a request for permission in those days and senior officers were expected to act on their own initiative. Popham may well have done so.

Popham arrived in the River Plate in June 1806. According to some accounts, he was assisted in navigating the Plate by a British agent. (In my book, Burke in the Land of Silver, the agent was James Burke who we know was active in the area at the time.) The Plate is certainly not an easy river to navigate. Popham was quoted at the time as saying, “It was a bit bumpy,” as his ships nearly grounded on sandbanks.

Popham’s army was commanded by Colonel William Beresford. The illegitimate son of the 2nd Earl of Tyrone, Beresford had served under Wellington and was held by many (though not Wellington himself) to have a less than perfect grasp of military strategy. He landed his troops at Quilmes, fifteen miles from Buenos Aires. The Spanish did not have enough troops to mount an adequate defence and, as Popham had predicted, Beresford had an easy march, brushing aside the meagre forces sent to oppose him. On the 27 June 1806, Buenos Aires surrendered.

The Spanish governor had fled with the treasury, but Popham sent soldiers in pursuit and succeeded in capturing the money – over a million Spanish dollars. The treasure was duly sent to London where it was paraded through the streets in eight large wagons, each carrying five tons of silver pesos. £296,187 3s 2d was distributed as prize-money and Popham and Beresford were both made Freemen of the City of London.

Resolved unanimously, That the Thanks of this Court be given to Major-General Beresford and, Commodore Sir Hope Popham, and the Officers and Men under their respective Commands, for their very gallant Conduct, and the very important Services rendered by them in the capture of Buenos Ayres, at once opening a new Source of Commerce to the Manufactories of Great Britain, and depriving her Enemies one of the richest and extensive Colonies in her Possession.

Resolved unanimously, That the Freedom of this City, and a sword of the value of Two Hundred Guineas, be presented to Major-General Beresford, as the Testimony of the high Esteem which this Court entertains of his very meritorious Services.

Resolved unanimously, That the Freedom of this City, and a sword of the value of Two Hundred Guineas, be presented to Commodore Sir Home Popham, as the Testimony of the high Esteem which this Court entertains of his very meritorious Conduct.

– Chamber of the Guildhall of the city of London Thursday, 2 October 1806

There was some embarrassment when news reached London that by the time Popham and Beresford were being honoured, the Spaniards had already recaptured Buenos Aires. Popham was eventually court-martialed, but was let off with only a censure. It doesn’t seem to have done any damage to his career. He was made a rear admiral in 1814 and awarded a KCB in 1815.

Burke in the Land of Silver

The first of my books about James Burke was inspired by the events surrounding this invasion. James Burke was a real person and much of the story, with its double-dealing, wild women and political intrigue is closely based on fact. A thrilling tale from a time when the world was in turmoil and a few good men (or, I’m afraid, quite often bad men) could change the course of history. Burke in the Land of Silver is available in paperback or as an e-book. You can buy it on Amazon or, in the USA, also through Simon and Schuster. Here’s the link: mybook.to/LandofSilver

Picture credit

‘The Glorious Conquest of Buenos Ayres by the British Forces, 27th June 1806’ Coloured woodcut, published by G Thompson, 1806. Copyright National Army Museum and reproduced with permission.

by TCW | Jun 21, 2019 | Napoleonic history

As promised in last week’s blog, this weekend we made a visit to Apsley House, where there were some special events to mark Waterloo Weekend.

Apsley House is well worth a visit in any case. Once known as ‘Number One, London’, because it was the first house that you came to when entering the city from the west, Apsley House was the home of the Duke of Wellington. The present Duke still lives on the upper floors, but the two lower floors and the basement are now open to the public. The décor and furnishings are those of a very grand Georgian House, but its main interest is obviously its connection with the Duke. Wellington was well aware of his place in history, and Apsley House (complete, even when he was living there, with its own museum of Wellington-related memorabilia) is the history of the British victory expressed as architecture.

This weekend, though, we could only spend a short time there, so we concentrated on the special events for Waterloo Weekend.

The Rifles

Before the house was open to the public, representatives of the 95th Rifles marched into the forecourt of Apsley House and gave a demonstration of drill.

Even with just four men, making all the prescribed moves smartly together is much harder than it looks, and the 95th were impressive. It was interesting to see how close together they marched, presumably reflecting the fact that in the line the ranks of infantry would be packed together much more tightly than you would expect nowadays – “bollocks to backsides” as one re-enactor explained to me. (Not this weekend, when everyone was on their best behaviour.) Later I had a chance to talk to a couple of the men who were inside the house displaying their equipment. As ever when I meet re-enactors, I learned lots of stuff that isn’t immediately obvious when you read about the period. For example, I had always thought of the flints used in a flintlock rifle as being similar to the sort of flints that you would find in a cigarette lighter. After all, you only need one spark and how hard can that be? In fact, the flints were decent size pieces of stone about three quarters of an inch wide. I was told that the flints for the Brown Bess musket were even bigger.

The Brown Bess was generally bigger in every respect. Muskets need a longer barrel than rifles but this meant that when Rifleman was standing alongside other infantry to resist a cavalry attack there was a danger that the line of bayonets that the enemy faced would be ragged, because the weapons of the Rifles were so much shorter than the muskets of the regular infantry. The Rifleman I talked to showed how this was addressed by issuing rifles with sword bayonets, so long that they could stand alongside other infantry to make an unbroken line of steel. The sword bayonets had the additional advantage that they could also be used as swords in close combat. The length of the bayonets is clearly shown in the photo below. (I hope the sergeant had words with the man furthest from the camera or perhaps he was just preparing to attack a very short Frenchman.)

The Riflemen carried pre-cut patches – pieces of paper that were wrapped around the musket ball so that it gripped in the rifling of the barrel. At this stage rifle ammunition was issued as loose balls rather than pre-prepared cartridges and loading was a slow and laborious process. Apparently early Riflemen were sometimes issued with mallets to help them force the ramrod down the barrel. It was not surprising that the Rifleman I spoke to said that after the first couple of shots they were likely to load without patches as once the enemy was near the advantage of accuracy was not worth the reduction in rate of fire.

There was a tent in the courtyard where one lucky Rifleman could shelter from the weather. Presumably he was an officer, because British troops at this period were seldom afforded the luxury of tents. Hanging around the real fighting men, as the artillery so often do, were a couple of representatives of the Royal Horse Artillery, looking very splendid in uniforms which, confusingly, were predominantly blue – the colour of the enemy’s uniform. There were a lot of different colours of uniforms among the Allied armies and what we nowadays call blue-on-blue (though I guess then they might have been red-on-blue-with-orange-facings-because-that-won’t-confuse-anyone) casualties were not uncommon. The RHA did have very pretty uniforms though (and they don’t half look smarter than the representatives of 2019 hanging around the place).

There were a few women around too, adding a touch of glamour. I was particularly impressed with this outfit, which was a riding habit with a jacket and bonnet that made clear the lady’s admiration for the Rifles.

It was a useful reminder that the war affected every aspect of society, including fashion. The idea of clothing that showed your support for particular regiments was apparently quite common, although it’s not something that I’ve come across before. I must admit it seems more credible to me than the idea popularised by Jane Austen fans that the war was something separate from everyday life back home in England.

The Surgeon

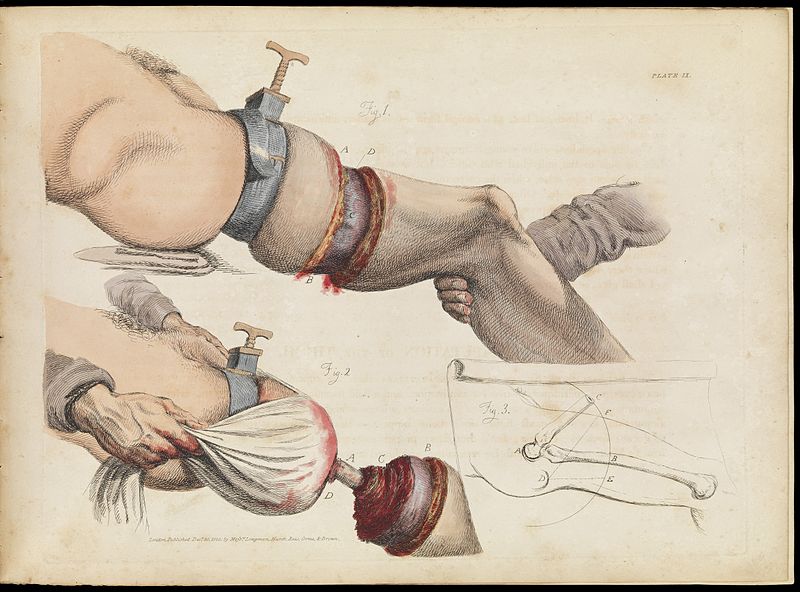

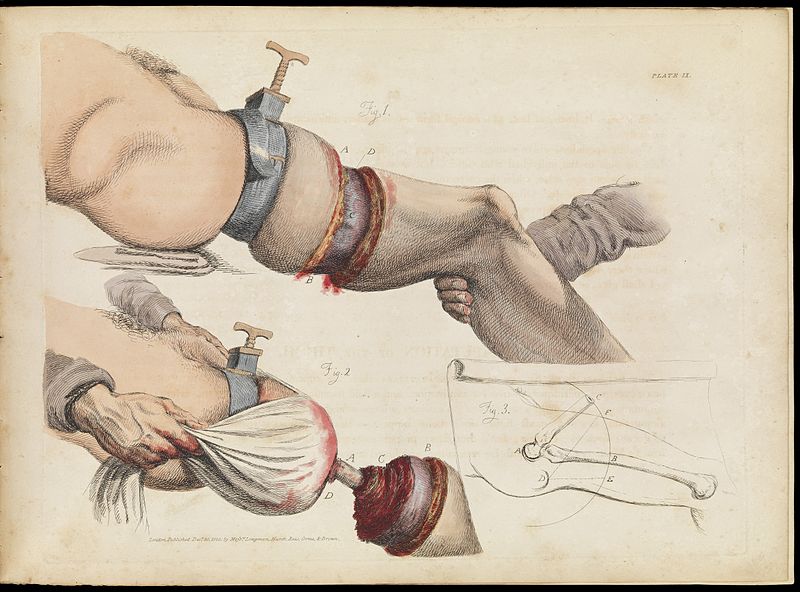

Paul Harding gave an interesting talk on surgery in the aftermath of Napoleon. I’ve been to a talk on this before, given by a well-regarded expert who showed off his case of surgical instruments, which was rather like the one in this (unfortunately rather blurry) picture from the National Army Museum.

Mr Harding’s approach was less refined. A few drills and saws and a bloody bandage were scattered around on his table as he explained how he would treat various wounds in those lucky enough to make it as far as the field hospital at Waterloo, some distance in the rear. He pointed out that operating on the field of battle was impractical and, probably more importantly as far as he was concerned, left surgeons open to the possibility of getting killed. There weren’t a lot of them and they had no intention of dying they could avoid it.

Mr Harding’s approach was down and dirty. Finding musket balls with a probe was all well and good, but nothing beat sticking your finger into the bullet hole. Cauterisation might create problems in the future, but applying a white hot iron to bleeding wounds provided a quick fix.

I learned some interesting things I didn’t know before. Patients were generally operated on while sitting, rather than laid on a table. They’d be sober too: rum might be offered after surgery but the last thing he wanted while operating was the struggles of a drunken man. He also explained that the idea that amputations were done very quickly is a little misleading. If you cut through skin and flesh your saw clogs up, so the surgeon prepares for the amputation by making an incision in the skin and drawing the flesh back to expose the bone at the point where the cut has to be made. This approach is illustrated very clearly in this contemporary drawing.

The cutting of the bone was, indeed, done very quickly, but the whole operation could easily take twenty minutes without anaesthesia. Most patients would fall unconscious after only a few minutes and the physiological response to the shock of surgery meant they would often survive the actual operation, but the after-effects of shock, infection (equipment was often not cleaned, let alone disinfected, between operations) and pre-existing weakness meant that Mr Harding’s best estimate for post-operative survival rates was about 9%.

We were given a quick introduction to trepanning and told how to leave a decent flap of skin to sew over the stump. (Lots of surgeons didn’t so that wooden prosthetics will be fitted straight against areas of scar tissue. You might be able to imagine the pain this would inflict, but you’ll probably be happier if you don’t.) Fascinating stuff and makes you realise just how glad you are to live in an age of anaesthetics and antibiotics.

For more about Apsley House:

I’ve written more about the house here: http://tomwilliamsauthor.co.uk/apsley-house-a-statement-in-stone/

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all who worked on this at Apsley House and who were so patient answering my questions.

Special thanks to Marcus Cribb at Apsley House for the photo of the surgeon’s demonstration and to Claire Donovan for posing in her splendid dress.

The illustration of a leg amputation by Sir Charles Bell is in the Wellcome collection and reproduced with permission.

Burke at Waterloo

If you would like to read a ripping yarn that climaxes at the Battle of Waterloo (and which does tell you an awful lot about what it must have been like), then I’d love you to consider Burke at Waterloo. It does tend to get slightly more sales at this time of year, and because of the way Amazon works the book gets much more visibility if you buy now rather than waiting until you go on holiday. If you enjoy reading me wittering on about the events in Belgium 200+ years ago, I’d really appreciate it if you could buy the book. Thank you.

Here’s the link: mybook.to/BurkeWaterloo

by TCW | Jun 14, 2019 | Napoleonic history

We’re coming up to the anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June. I’ve written a book which climaxes at Waterloo: Burke at Waterloo. It’s a lot of fun and also gives you a useful summary of the events leading up to Waterloo and the battle itself. According to the mysterious laws of promotional blogging, because I’ve written this book I now have to write about the history. The problem is that the anniversary of Waterloo comes round every year and I covered it quite thoroughly last year.

It’s impossible, though, to ignore Waterloo completely. This weekend we may well end up going to the special events at Wellington’s London home, Apsley House. For those more adventurous, there is an annual re-enactment every year at Waterloo. This year it will be next weekend (22-23 June).

Why do the British get so excited about Waterloo? I was once talking about this to a French army officer who suggested that the French really were not interested in Waterloo, but were more enthusiastic about Austerlitz. There is no doubt that nations do tend to remember the battles they won, but Wellington won a lot of battles in the Peninsula and their anniversaries pass by with hardly any commemoration at all.

Field at Waterloo from the top of the Lion’s Mound

Waterloo holds a place in British history which is completely disproportionate to its actual military importance. Bloody as it was, it was far from the bloodiest battle of the Napoleonic wars, and the British have always overstated its strategic significance. In truth, the era of Napoleon had ended the previous year with the fall of Paris and the Emperor’s exile to Elba. Waterloo was rather a sad coda to the story of French military supremacy in Europe.

Waterloo, though, was a decisive victory which could be presented as a uniquely British achievement. (It wasn’t – fewer than half of those fighting Napoleon were British). Britain had been central to the struggle against Napoleon, bankrolling the armies of other states across Europe and maintaining control of the seas. It was only at Waterloo, though, that the British Army directly engaged French forces on the main front of the war. The battle cemented Britain’s position as one of the leading powers of Europe with a decisive influence in the settlement of the continent after the Allied victory.

For 200 years following Waterloo Britain saw itself as arguably the most important military and political power in Western Europe. This was not a view that would have been shared by other countries and its effects were not always positive. For example, some commentators consider that it was victory at Waterloo that convinced the British that they did not need the sort of military reforms that were seen in, for example, Prussia. The failure of the British army to adapt to the new forms of warfare that were emerging in the 19th century was a contributing factor to the disaster of the Crimean War. Yes, we were on the winning side, but militarily the campaign did not reflect well on the British Army. British soldiers behaved heroically, but their leadership let them down time and time again, not only in well-publicised disasters like the Charge of the Light Brigade but in less high profile – though arguably more significant – failures in supply and communications.

Politically, too, the myth of British exceptionalism, of which Waterloo was a significant element, has often damaged our relationships with the rest of Europe, culminating in the rejection of continuing EU membership. For better or worse, the reverberations of Waterloo continue to resonate more than 200 years later.

We are probably right to remember Waterloo. It marked the end of an era. What historians call “the long 18th century” ended on that bloody field just south of Brussels. The world was, indeed, never quite the same again – but the changes that we were to see in the 19th century were probably inevitable anyway. The growth of industrialisation, the increase in the franchise, the rise of the middle classes, the dramatic changes brought about by improvements in transport (notably the railways) and communication (like the electric telegraph) – all these things would almost certainly have happened whoever had won at Waterloo. 18 June, 1815, though, is one of those milestones in history. The journey does not radically change as we pass a milestone, but it is the milestones that remind us where we are.

If you have the chance this weekend or next, it’s worth thinking about that milestone and how the world has changed since and, perhaps, how we want it to change in the future.

Burke at Waterloo

Of course, you could commemorate the battle by reading my book. Burke at Waterloo starts off as a straightforward spy story. Burke is in Paris to foil an attempt on the Duke of Wellington’s life. (Yes, there really were attempts on Wellington’s life.) Burke’s pursuit of the Bonapartist spy leading plot takes him to Brussels with a climax at Waterloo. Military history enthusiasts are likely to enjoy the details of the Battle of Waterloo and of the (nowadays sadly neglected) Battle of Quatre Bras two days earlier. Everybody else can just relax and enjoy the spy story.

Burke at Waterloo is available on Kindle or in paperback. In the USA it is also distributed by Simon & Schuster.

Image at top of page is Wellington at Waterloo by Robert Hillingford

by TCW | Jun 4, 2019 | Book review

When I agreed to review Rees-Mogg’s book, The Victorians for the Historical Novel Society I hadn’t seen the tsunami of negative reviews that it has received. When it arrived I approached nervously, both because it’s a bit unnerving to settle down with a 439 page book that everybody has said is awful, and because if I didn’t like it either, what on earth was I going to say in the review?

The book is indeed terrible. But I think that many of the reviewers have done it something of an injustice. Rees-Mogg has set out to discuss the lives of twelve Victorians – “Twelve Titans Who Forged Britain” – and this has led most people to see this book as essentially a history of the Victorian age seen through some of its leading figures. I think this fundamentally misunderstand is what Rees-Mogg is trying to achieve.

Jacob Rees-Mogg

Jacob Rees-Mogg

The book is not in any normal sense a historical work. It does have some history, but this is used merely to illustrate Rees-Mogg’s view of the world and, given the significant role he plays in our current politics, understanding his view of the world is probably a worthwhile undertaking.

Rees-Mogg appears driven by two things – his Catholicism and his membership of the Conservative Party. The book does give me a much better understanding of the history of the Conservative party and the way that it developed during the 19th century. In fact, I suspect that Rees-Mogg could write a useful book about the party. He explains how Peel’s Tamworth Manifesto (1834) “marks … the beginning of the contemporary British Conservative Party”. It was a serendipitous moment to shape a political party because “The General Election of 1835 … was the first election when papers published lists of candidates with ‘party’ labels attached.” Peel went on, of course, to split the party over his repeal of the Corn Laws and Rees-Mogg’s explanation of the background to this and the way in which the party eventually recovered from the split is a useful summary for those of us who are vaguely aware of what happened without being clear as to the detail. It would be clearer still if this was arranged as a straightforward history of the party rather than having the split in a chapter about Peel and the details of the recovery in a much later chapter about Disraeli. Even so, the history of the party is well presented. For anyone who, like Rees-Mogg, cares about these things, Disraeli’s consolidation of the party’s organisation is a significant historical event.

“It was at this time Conservative Central Office evolved as the prime organisational power in the party with sub-bodies established to reinforce its power and influence in the country. One such was the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations, that tentacle of Central Office in charge of organising within newly enfranchised urban communities…”

Sadly, Rees-Mogg is not writing a history of the Conservative party, but the lives of twelve great Victorians. The obsession with the party leads to some distortions so extraordinary as to be almost comic. So these are the closing words of his chapter on Peel:

“In the end, it is only possible to recognise the majestic extent of Peel’s achievement by realising what it avoided. For without the party and its philosophy he bequeathed to the nation, there is little reason to suppose we would have coped with change any better than other countries did. A negative achievement when seen in full, perhaps, but a vital one, and one for which we should still be thankful.”

Robert Peel

Robert Peel

Peel’s political career started as Chief Secretary to Ireland. He was the chairman of the Bullion Committee that returned Britain to the gold standard. As Home Secretary he founded the Metropolitan police, and is widely regarded as the father of modern British policing. As prime minister he was responsible for, amongst other things, the Mines and Collieries Act 1842, the Income Tax Act 1842, the Factories Act 1844 and the Railway Regulation Act 1844. Whilst historians recognise his achievement in shaping the modern Conservative Party, Rees-Mogg’s emphasis on this aspect of his career appears excessive.

When he is not viewing his subjects through the lens of his political interests, Rees-Mogg concentrates on their religious views. Pugin, for example, is included as one of the “twelve Titans”. Even if you are a fan of his architecture – and as Rees-Mogg admits, “Even in his own lifetime … his people virtually lost sight of his achievement” – it is difficult to see the basis on which he is one of the twelve most important men of his time. The answer is that he was “God’s architect”, his designs intended to reflect the glory of a Catholic (or, when occasion demanded, an Anglo-Catholic) deity. Gladstone’s Whiggery is forgiven for the “deeply felt sense of religion” that influenced his outlook. He was a High Anglican who fought for disestablishment of the Anglican church in Ireland (favouring the Catholic cause) though for ten years he refused to speak to his one-time friend, Manning, who had been an Anglican cleric before converting to Catholicism eventually becoming Archbishop of Westminster.

Pugin was mainly responsible for the interior detailing of Parliament, but he did design the clock tower

It is with the chapter on General Gordon that the discussion of religious beliefs carries us to the edge of sanity. Gordon was far from the most important martial figure of his age. He fought in the military shambles that was the Crimean War and then beat the Chinese in the Second Opium War, a conflict in which the technological superiority of the European armies meant that the outcome was never in serious doubt. Still in China, he assisted the Chinese government in putting down the Taiping Rebellion before (with British government approval) entering the service of the Khedive of Egypt in 1873 where he became Governor-General of the Sudan. He stayed in the Sudan until 1880, when he returned to England. However, a rebellion in Sudan led to Gladstone’s government deciding to withdraw all British and Egyptian troops and administrators in the upper Nile Valley. Gordon objected and went to the press advocating massive intervention in the Sudan to crush the uprising. Public opinion backed him and Gladstone, feeling he was losing control of the situation, agreed that Gordon could go to Khartoum and report but the government policy was to continue to be an evacuation of British and Egyptian personnel. On his arrival at Khartoum, Gordon ignored his orders and began preparations for a siege. His position was militarily impossible. Again, public opinion took his side, insisting that a relief force be sent to break the siege. It arrived too late. By the time the British arrived the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed. About 10,000 people died in the course of the assault.

General Gordon

General Gordon

It can be argued that Gordon’s military career, despite his popularity with the public, was unimpressive. What makes him stand out for Rees-Mogg seems to be his religious beliefs.

“In this chapter, the aim is to re-examine this British exemplar… In particular to emphasise the forgotten aspects of his story, his deep and unique religiosity…”

What Rees-Mogg sees as a “deep and unique religiosity” most 21st century readers may well view as barking mad.

“He came to believe in the pre-existence of the soul. The body was a ‘sheath’ in which the soul was placed at birth, to be awoken when union with Christ was achieved… [O]nce this vision occurred ‘the now raised and quickened soul will grope its way out of its shell’ where … it will contend with the body, often being nearly extinguished but never quite, till the body gives up the struggle in natural death’ and the much longed for homecoming is achieved.”

Bluntly put, Gordon had a death wish. Rees-Mogg reports him as saying, when threatened by King John IV of Ethiopia:

“I am always ready to die, and so far from fearing you putting me to death, you will confer a favour on me by so doing, for you will be doing for me that which I am precluded by my religious scruples from doing for myself.”

In Khartoum, Gordon finally achieved the end he had sought so enthusiastically for so long. It is just unfortunate that 10,000 others had to die alongside him.

Why does Rees-Mogg enthuse about somebody who appears not only, to put it mildly, eccentric, but dangerously eccentric? The answer appears to be that the author holds many beliefs that have more in common with those held by the Victorians than one might expect to find in a 21st century Member of Parliament. He is obviously a believer in the Great Man theory of history, but he also believes that Providence plays a direct role in guiding historical events. Writing about Sleeman (famous for first discovering and then eliminating Thugee in India) he says:

“… perhaps fate or destiny had ordained precisely that Sleeman be on the spot, for it needed such a man as he to deal with a situation that so many before him had failed to resolve.”

Rees-Mogg’s vision of Conservatism and his religious beliefs are firmly rooted in his view of the 19th-century, but this is a 19th century than never really existed. The Victorians seeks to delineate a myth:

“These heroes of old who possessed belief and patriotism, a sense of duty, a confidence in progress and knowledge of civilisation have shown us what can be done… The truth is that Victorian Britain was [… a society of] greatness, nobility, and good sense.”

Like all myths, it depends on willing acceptance by its audience. Mythology is not about fact and detail – hence, presumably, the absence of footnotes, references (there is just a bibliography of three pages of secondary sources), or even an index. Instead we have a broad brush overview of twelve of Rees-Mogg’s heroes. They are not, even by his own account, particularly representative. Discussing the Jamaica Committee, he lists “some of the most illustrious worthies of liberal Britain … Charles Darwin, John Stuart Mill and the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley.” None feature in this book, their liberalism alone being enough to disqualify them. The book ignores, or dismisses out of hand, most controversial issues. (My personal favourite was that “the First Opium War proved an unqualified British success… A Second Opium War (1856-60) would complete the mission to British satisfaction.” This casually dismisses probably the most outrageous aggression of a century that provides stiff competition in this field.)

Sadly, the fantasy idyll of Victorian England was cruelly facing reality even while the book was being printed. For Rees-Mogg, the great strength bequeathed to us by the Victorians was the stability of our political system and our constitution.

“… the unique characteristics and glorious flexibility of the British constitution. This was an entity which could, unlike its known, codified equivalent, respond swiftly and decisively to the political needs of the nation.”

As Britain and its political class become the laughing stock of the world, it is worth knowing that one of the architects of our national humiliation is a man whose beliefs are based on a badly researched, carelessly presented, largely imaginary past. Rees-Mogg’s vision of the Conservative Party – a vision that Peel and Disraeli would both recoil from – and his messianic conviction that Providence will step in when the nation needs to be saved, both make him utterly unfitted for public office. If this book has only made that clear, reading it is not time entirely wasted.

Image credits

Jacob Rees-Mogg: official photograph by Chris McAndrew

Peel: Duyckinick, Evert A. Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women in Europe and America. New York: Johnson, Wilson & Company, 1873. Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.

Big Ben: Photo by DAVID ILIFF. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Gordon: Geruzet Frères – Belgian (active c. 1870-1889) – Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum, Historical Photographs and Special Visual Collections Department, Fine Arts Library

Why am I writing this?

I’m not an expert on the Victorians. Victoria was on the throne a long time and a lot happened then. But my books about John Williamson are set mainly in the 1850s and their theme is the contradictions and complexities of Empire and the Victorian age. It is fair to say that they give a rather more nuanced view of this period than Rees-Mogg (and feature some rather more interesting Victorians, including James Brooke, whose inclusion would have made Rees-Mogg’s book a lot more interesting). If you want to know more about this series of books, please have a look at my blog post on the Williamson Papers.

by TCW | May 31, 2019 | Uncategorized

I’ve been experimenting with writing contemporary fiction. It’s been fun. The best thing about it as being not having to do nearly so much research. Writers of contemporary fiction are always pointing out that they do research too, but finding out how you would prevent blood from clotting, or how many seats there are in an average West End theatre, or how long it takes to drive from Nottingham to Dundee – these things took me rather less time than exploring exactly what life was like in Buenos Aires in the early 19th century.

The starting point for research usually involves a lot of reading. This used to mean weeks spent in libraries, but since the massive increase in the availability of books online, it now means spending weeks in front of screens. I’m lucky because my books are mostly set in the 19th century and I can read an enormous amount of contemporary material without ever leaving my desk.

Nice as my desk is, I do like to get out every now and then and research trips away are always fun.

Burke in the Land of Silver was the first book I wrote about James Burke and it is based very closely on the events of his life. The most important parts of the story are set in Buenos Aires and, as I’ve always liked Argentina, that was the perfect excuse for the greatest research trip I’ve had.

The buildings here haven’t changed much in two centuries

The buildings here haven’t changed much in two centuries

Buenos Aires is a huge modern city, but at the centre some streets have changed very little in two hundred years. I spent days walking around them, taking photographs to remind myself what they look like and finding paintings in the local museums that showed them as they were then. I explored the remains of the old Spanish fort that now lie underneath the presidential palace and I admired the British flags captured during the two British attacks on the city.

I was lucky in that the porteños (the people of Buenos Aires) are fiercely proud of their country and the city is full of museums with fascinating material about their early history.

Pioneer wagon – Criollo Museum – Matadores

There is more to Argentina than Buenos Aires, though, and Burke did leave the city to explore the countryside. His adventures start with a visit to an estancia on the pampas where he rides out with the gauchos tending their cattle. We took a day trip to San Antonio, where there is a museum of rural Argentine life that features a farmhouse of the period, which became the model for the one Burke visits in the book. Of course, we could hardly ride out with the gauchos. No, that had to wait for another trip that featured an unforgettable morning galloping across the plain while real working cowboys lassoed the new-born calves to check their health.

Oscar – the head gaucho

The maddest bit of research, though, was my attempt to recreate Burke’s ride across the Andes to Chile. In Burke in the Land of Silver I have him making the crossing around April, in the southern autumn. (I can’t swear he really did, but the timing makes sense.) The crossing at that time of year is considered dangerous because of the intense cold at altitude. When I was writing about it, I found it very difficult to visualise, so, in the interests of research, I went to the Andes and tried to ride across. We did it in October, so conditions shouldn’t have been that different, except that we had to face the winter snows that had yet to thaw.

It was a crazy thing to do and involved nights spent at 3,000 metres in a stone hut without any heating. I have never felt so cold in my life! Eventually the snow got too deep for the horses and we had to give up. In the end the trip contributed only a page or so to the book, but I like to think it’s a good page.

Historical research is hard – but it does provide the writer with some amazing experiences.

Burke in the Land of Silver

If you want to read what it’s like crossing the Andes in the snow, or get an idea of life in Buenos Aires 200 years ago, or just enjoy an exciting tale of British secret agents, wanton women, dastardly French spies, and adventures in the Argentine pampas, you can buy Burke in the Land of Silver in paperback or as an e-book. It’s available on Amazon or, in the USA, also through Simon and Schuster. Here’s the link: mybook.to/LandofSilver

Jacob Rees-Mogg

Jacob Rees-Mogg Robert Peel

Robert Peel

General Gordon

General Gordon

The buildings here haven’t changed much in two centuries

The buildings here haven’t changed much in two centuries