As promised in last week’s blog, this weekend we made a visit to Apsley House, where there were some special events to mark Waterloo Weekend.

Apsley House is well worth a visit in any case. Once known as ‘Number One, London’, because it was the first house that you came to when entering the city from the west, Apsley House was the home of the Duke of Wellington. The present Duke still lives on the upper floors, but the two lower floors and the basement are now open to the public. The décor and furnishings are those of a very grand Georgian House, but its main interest is obviously its connection with the Duke. Wellington was well aware of his place in history, and Apsley House (complete, even when he was living there, with its own museum of Wellington-related memorabilia) is the history of the British victory expressed as architecture.

This weekend, though, we could only spend a short time there, so we concentrated on the special events for Waterloo Weekend.

The Rifles

Before the house was open to the public, representatives of the 95th Rifles marched into the forecourt of Apsley House and gave a demonstration of drill.

Even with just four men, making all the prescribed moves smartly together is much harder than it looks, and the 95th were impressive. It was interesting to see how close together they marched, presumably reflecting the fact that in the line the ranks of infantry would be packed together much more tightly than you would expect nowadays – “bollocks to backsides” as one re-enactor explained to me. (Not this weekend, when everyone was on their best behaviour.) Later I had a chance to talk to a couple of the men who were inside the house displaying their equipment. As ever when I meet re-enactors, I learned lots of stuff that isn’t immediately obvious when you read about the period. For example, I had always thought of the flints used in a flintlock rifle as being similar to the sort of flints that you would find in a cigarette lighter. After all, you only need one spark and how hard can that be? In fact, the flints were decent size pieces of stone about three quarters of an inch wide. I was told that the flints for the Brown Bess musket were even bigger.

The Brown Bess was generally bigger in every respect. Muskets need a longer barrel than rifles but this meant that when Rifleman was standing alongside other infantry to resist a cavalry attack there was a danger that the line of bayonets that the enemy faced would be ragged, because the weapons of the Rifles were so much shorter than the muskets of the regular infantry. The Rifleman I talked to showed how this was addressed by issuing rifles with sword bayonets, so long that they could stand alongside other infantry to make an unbroken line of steel. The sword bayonets had the additional advantage that they could also be used as swords in close combat. The length of the bayonets is clearly shown in the photo below. (I hope the sergeant had words with the man furthest from the camera or perhaps he was just preparing to attack a very short Frenchman.)

The Riflemen carried pre-cut patches – pieces of paper that were wrapped around the musket ball so that it gripped in the rifling of the barrel. At this stage rifle ammunition was issued as loose balls rather than pre-prepared cartridges and loading was a slow and laborious process. Apparently early Riflemen were sometimes issued with mallets to help them force the ramrod down the barrel. It was not surprising that the Rifleman I spoke to said that after the first couple of shots they were likely to load without patches as once the enemy was near the advantage of accuracy was not worth the reduction in rate of fire.

There was a tent in the courtyard where one lucky Rifleman could shelter from the weather. Presumably he was an officer, because British troops at this period were seldom afforded the luxury of tents. Hanging around the real fighting men, as the artillery so often do, were a couple of representatives of the Royal Horse Artillery, looking very splendid in uniforms which, confusingly, were predominantly blue – the colour of the enemy’s uniform. There were a lot of different colours of uniforms among the Allied armies and what we nowadays call blue-on-blue (though I guess then they might have been red-on-blue-with-orange-facings-because-that-won’t-confuse-anyone) casualties were not uncommon. The RHA did have very pretty uniforms though (and they don’t half look smarter than the representatives of 2019 hanging around the place).

There were a few women around too, adding a touch of glamour. I was particularly impressed with this outfit, which was a riding habit with a jacket and bonnet that made clear the lady’s admiration for the Rifles.

It was a useful reminder that the war affected every aspect of society, including fashion. The idea of clothing that showed your support for particular regiments was apparently quite common, although it’s not something that I’ve come across before. I must admit it seems more credible to me than the idea popularised by Jane Austen fans that the war was something separate from everyday life back home in England.

The Surgeon

Paul Harding gave an interesting talk on surgery in the aftermath of Napoleon. I’ve been to a talk on this before, given by a well-regarded expert who showed off his case of surgical instruments, which was rather like the one in this (unfortunately rather blurry) picture from the National Army Museum.

Mr Harding’s approach was less refined. A few drills and saws and a bloody bandage were scattered around on his table as he explained how he would treat various wounds in those lucky enough to make it as far as the field hospital at Waterloo, some distance in the rear. He pointed out that operating on the field of battle was impractical and, probably more importantly as far as he was concerned, left surgeons open to the possibility of getting killed. There weren’t a lot of them and they had no intention of dying they could avoid it.

Mr Harding’s approach was down and dirty. Finding musket balls with a probe was all well and good, but nothing beat sticking your finger into the bullet hole. Cauterisation might create problems in the future, but applying a white hot iron to bleeding wounds provided a quick fix.

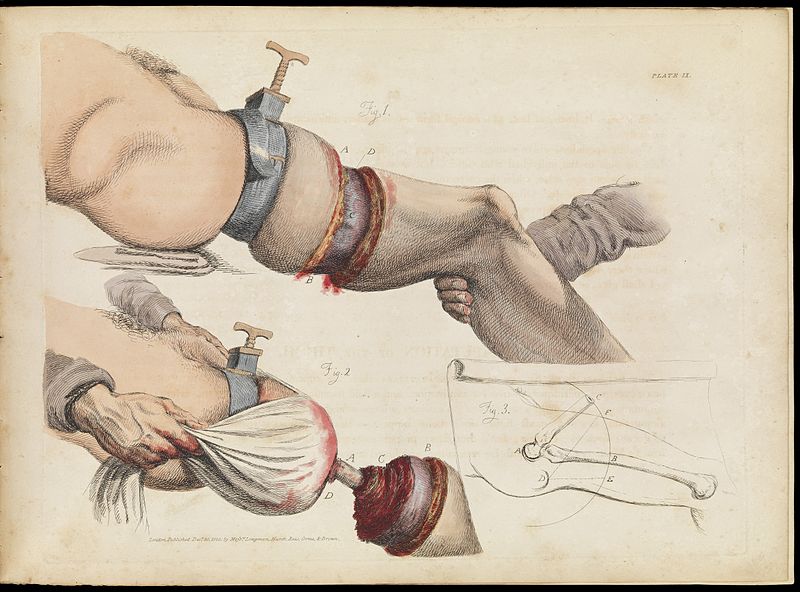

I learned some interesting things I didn’t know before. Patients were generally operated on while sitting, rather than laid on a table. They’d be sober too: rum might be offered after surgery but the last thing he wanted while operating was the struggles of a drunken man. He also explained that the idea that amputations were done very quickly is a little misleading. If you cut through skin and flesh your saw clogs up, so the surgeon prepares for the amputation by making an incision in the skin and drawing the flesh back to expose the bone at the point where the cut has to be made. This approach is illustrated very clearly in this contemporary drawing.

The cutting of the bone was, indeed, done very quickly, but the whole operation could easily take twenty minutes without anaesthesia. Most patients would fall unconscious after only a few minutes and the physiological response to the shock of surgery meant they would often survive the actual operation, but the after-effects of shock, infection (equipment was often not cleaned, let alone disinfected, between operations) and pre-existing weakness meant that Mr Harding’s best estimate for post-operative survival rates was about 9%.

We were given a quick introduction to trepanning and told how to leave a decent flap of skin to sew over the stump. (Lots of surgeons didn’t so that wooden prosthetics will be fitted straight against areas of scar tissue. You might be able to imagine the pain this would inflict, but you’ll probably be happier if you don’t.) Fascinating stuff and makes you realise just how glad you are to live in an age of anaesthetics and antibiotics.

For more about Apsley House:

I’ve written more about the house here: http://tomwilliamsauthor.co.uk/apsley-house-a-statement-in-stone/

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all who worked on this at Apsley House and who were so patient answering my questions.

Special thanks to Marcus Cribb at Apsley House for the photo of the surgeon’s demonstration and to Claire Donovan for posing in her splendid dress.

The illustration of a leg amputation by Sir Charles Bell is in the Wellcome collection and reproduced with permission.

Burke at Waterloo

If you would like to read a ripping yarn that climaxes at the Battle of Waterloo (and which does tell you an awful lot about what it must have been like), then I’d love you to consider Burke at Waterloo. It does tend to get slightly more sales at this time of year, and because of the way Amazon works the book gets much more visibility if you buy now rather than waiting until you go on holiday. If you enjoy reading me wittering on about the events in Belgium 200+ years ago, I’d really appreciate it if you could buy the book. Thank you.

Here’s the link: mybook.to/BurkeWaterloo