by TCW | Jul 23, 2019 | Book review

I’ve never reviewed two books by the same author in successive weeks before, but I’m happy to make an exception now.

My review of Frank Prem’s ‘Small Town Kid’ came out last week. Frank was pleased to see that I liked it, so he sent me a copy of his next, ‘Devil in the Wind’. It’s another book of free verse, this time inspired by the 2009 bushfires in Australia.

I generally take my time with poetry books, but I opened this one to make sure that my Kindle copy had downloaded properly and I was immediately gripped. I read it over the next couple of days, hardly an achievement because poetry books don’t have that many words in them, but not the way I would usually approach poems at all.

I found the work immensely moving. Frank does, admittedly, have spectacularly moving source material, but I vaguely remember reading about it in newspapers time and the naked facts don’t have the same gut wrenching impact as these verses.

As I said last week attitudes to poetry are inevitably subjective, and perhaps you won’t feel the same way about them as I did. If you go onto Amazon, though, ‘Look inside’ will let you read all but the last page of his ‘Prologue’ which grabbed me by the throat and pretty well forced me to read on. All I can suggest is that you do just that. If you like it, please buy the book. It’s wonderful.

by TCW | Jul 16, 2019 | Book review

When Frank Prem offered me a copy of his “free verse memoir” through a writers’ Facebook group I wasn’t at all sure that I wanted it. But then I reckoned the idea was so outrageous that I might as well read it anyway and I’m ever so glad that I did.

I wouldn’t exactly think of it as a free verse memoir. It’s definitely free verse – the absence of all punctuation and capitalisation gives it a very 1960s feel that I’m not sure improves it – but it’s not exactly a memoir. Rather it’s a chronological series of poems describing the author’s life growing up in small-town Australia. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book of poems and felt enthusiastic about all of them. There is a strong subjective element to poetry and what pleases one person won’t please another, but there are some real gems here. He captures a lot of the ambivalence of a young child’s feelings about life. He captures, too, a vanished way of living. There are poems about the dubious charms of the outhouse and the odiferous work of the night-soil men and then, later, a poem about the blasting of a sewerage line heralding a new world:

of filtration

and treatment plant

and of sculpted porcelain

It is, the title of the poem assures us, “the dawn of civilisation”.

There is a strong sense of place and time – not only the period, but slow cycle of the seasons and the events that mark their passing in this small town. Here’s the church fete:

once a year

it happens once a year

the noise shatters the afternoon

as an old ute with two loudspeakers attached above the roof of the cabin

does circuits of the town

and can be heard in a garbled blur

from three streets off

and not much better up close

but it doesn’t matter what they’re saying

because we already know

And bonfire night:

a couple of tuppenny bangers

and a short detour

to blow up the deputy headmaster’s mailbox

is an annual event

and he’s long practised

at straightening its swollen metal sites

on the morning after

As Frank grows older (there’s a nice poem called ‘growing pains’) girls feature more often, from the gentle innocence of ‘sweet maureen’

I rode my bike for sweet maureen

from beechworth to yackandandah

…

I was drawn

down the road

descending like a bullet

from the barrel of my rifle

drawn to ride

to sweet maureen

to the rather less innocent Judy.

judy runs the supermarket now

but I remember her as fifteen years

of laughing dark-brown eyes

that once upon a time

closed to kiss me

on a new year’s eve

in a crowded street

that vanished

for the whole

of one

single

moment

As the book goes on, the sad reality of the lives of some of these women is cruelly exposed, like the popular girl at school who

… stopped coming

to classes

then moved away

before the baby arrived

Eventually, though, there is love:

hey I think we’ll get by

won’t our folks

be surprised

they think that we’re lost

but I don’t suppose

we’re so bad

and a child.

I watch over

my tiny wonder

Despite the pessimism that slips in through many of the poems

we were formed

as small-town kids

was there ever a chance

this is, in the end, a life affirming collection of poems. I’m glad I took the chance to read it.

Small Town Kid is available on Amazon in paperback or as an e-book: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B07L63WS2D

You can hear Frank reading some of his poetry on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvfW2WowqY1euO-Cj76LDKg

Frank’s second book, Devil in the Wind (poems inspired by the bush fires of 2009) is also available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B07Q9YLD8V

by TCW | Jul 12, 2019 | Uncategorized

The Pre-Raphaelite angels we looked at last week (and which are shown again in the heading to this page) may not be to everybody’s taste, but these other angels, high on the ceiling, are a restoration of the original imagery, keeping close to what was there before.

The nave ceiling is another piece of Victorian restoration which I think works very well.

It’s a major piece of work because the cathedral is 537ft (161m) long and claims to have the longest nave in the country. I don’t know if that is really true, but it’s certainly very long. Here’s the view from the West door.

The Victorians were also responsible for painting some of the walls in a way I found very convincing.

Victorian restoration – but convincing.

There are some of the original wall paintings still visible, like this 14th century artwork from St Edmund’s Chapel.

More collapsing towers and other unfortunate incidents

The great West tower (215ft or 66m high) was completed in the 12th century, but in 1392 someone had the brilliant idea of adding an octagonal tower onto the top to house a belfry. Have we mentioned clay soil? The north-west transept collapsed shortly after, leaving the asymmetrical front we see today, though extensive buttressing has kept the tower itself standing. Ironically the belfry is not used.

It was probably the monks’ mania for continually expanding the cathedral that led to the collapse of the central spire. In the 14th century they decided to build a Lady Chapel just north of the main cathedral building. You can see it in this photo taken from the roof.

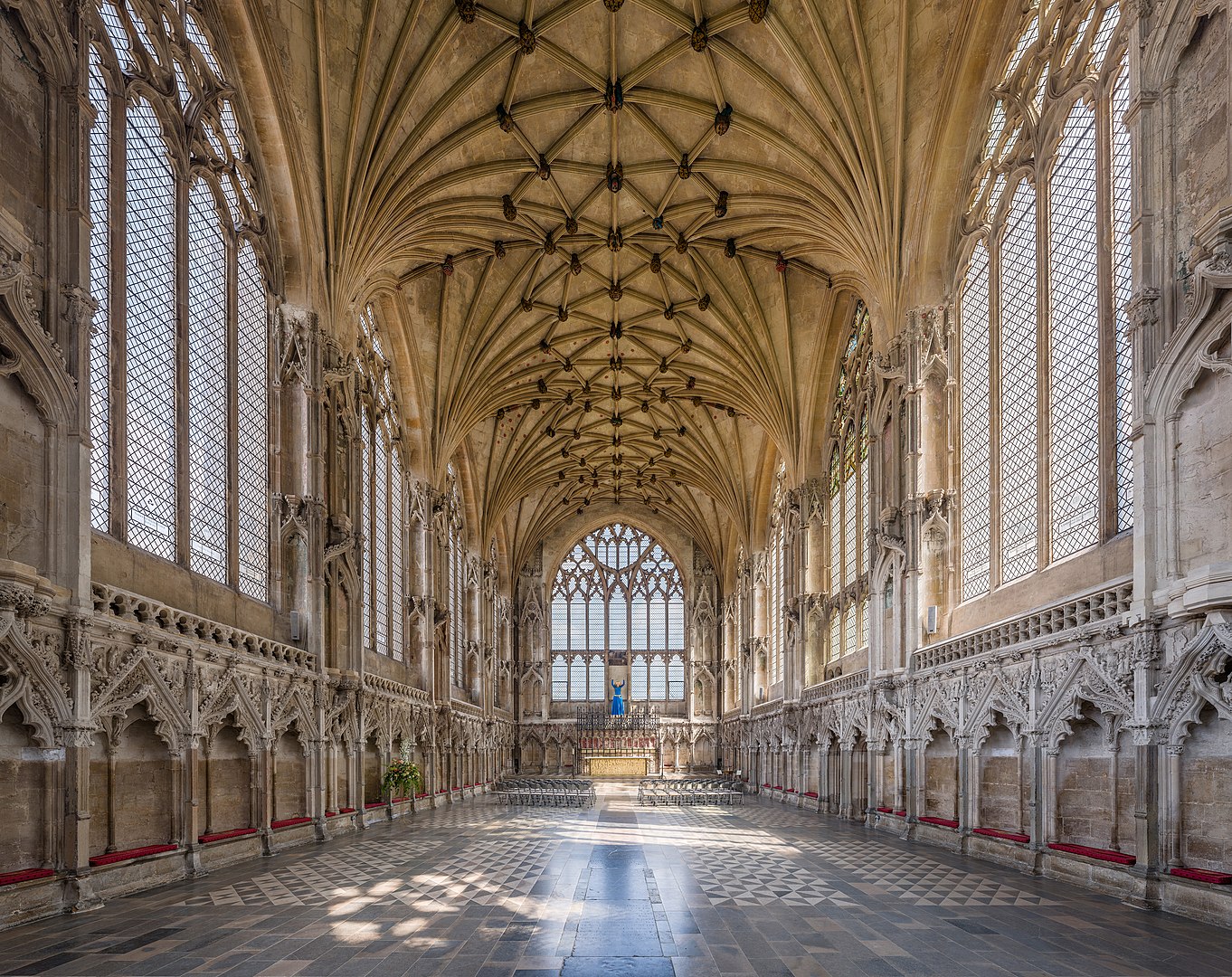

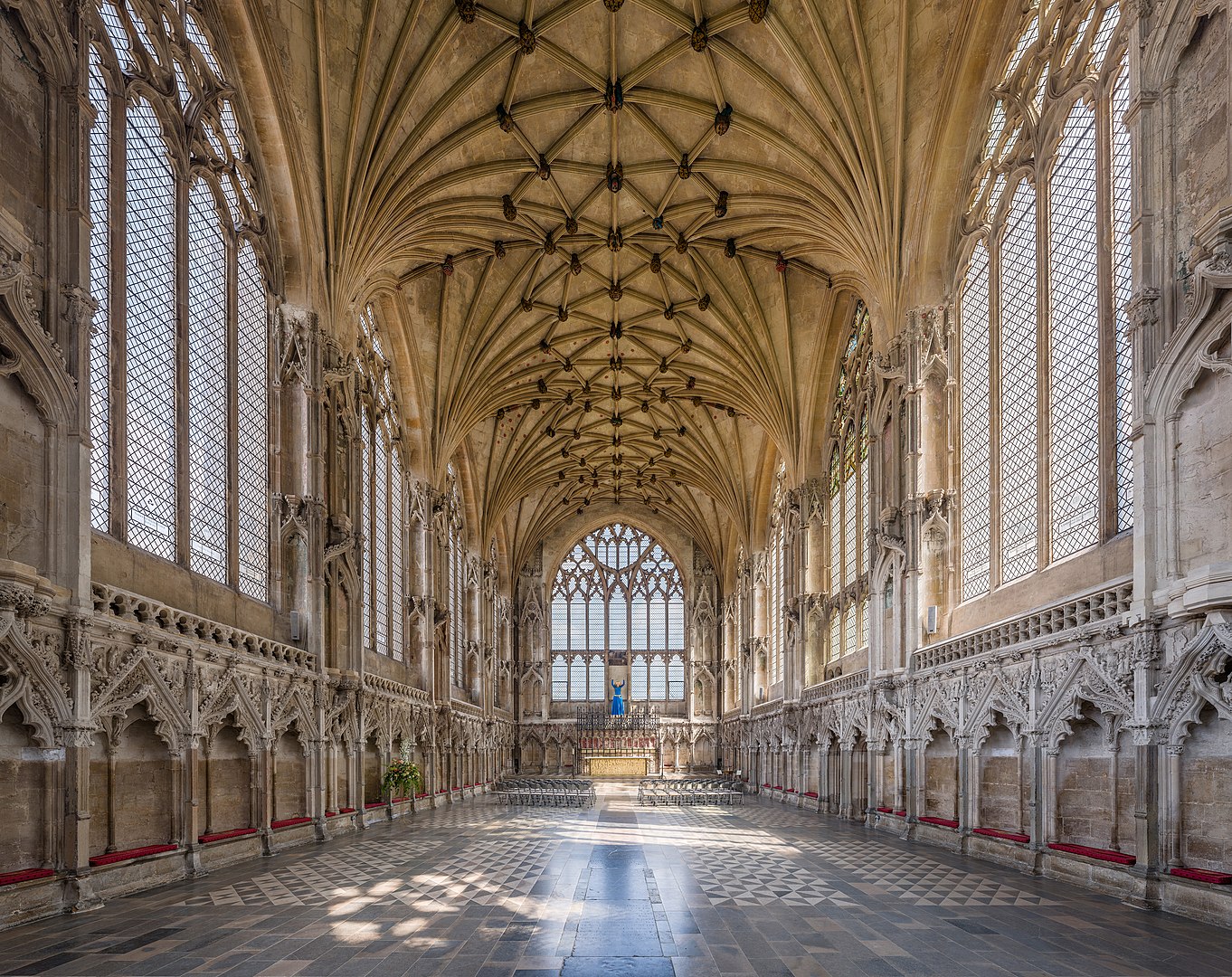

The Lady Chapel is on the left and, as you can see, dangerously close to the main building. The result was that the digging of the foundations led to changes in the water table which was probably the reason for the collapse of the central tower. This foolishness has, however, left us not only with the stunning octagonal tower and lantern, but with the largest Lady Chapel in England. Originally it would have had stained-glass windows and a screen across the centre dividing the area used by the monks from that used by the laity. The Reformation, though, put an end to that with the smashing of the stained-glass windows and the destruction of the screen. The chapel only survived at all by being rededicated as a separate church. The result, though, is that now it has been taken back as part of the cathedral it is an astonishingly light and airy space and very beautiful. Stupidly, I didn’t take a photograph of it, so this one is courtesy of David Iliff.

It wasn’t just the Lady Chapel but suffered during the Reformation. Throughout the cathedral stained-glass was destroyed and the statues of the saints which used to fill niches all around the building were either removed or defaced. It was then that the splendid shrine of St Ethelreda vanished forever, leaving just a pile of stones that may or may not once have been part of it.

Lots of churches came in for similar treatment during the Civil War, but people in Ely are quick to deny that any of the damage to the cathedral was done then. Oliver Cromwell was a local lad and seems to have been unwilling to damage the place. The local vicar was told that he must stop choral services (the Puritans disapproved of music in church) and when he refused to do so he and his congregation were driven out of the church. There seems to be some uncertainty as to what happened next, though some stories suggest that the place (as with many other churches) was used for stabling Parliamentary cavalry. In any case, there was no permanent harm and with the Restoration the Dean and Chapter were re-appointed and started a programme of refurbishment. Since then the cathedral has undergone several cycles of repair and restoration, which continue up to the latest work to repair roofing on the octagonal tower which is still ongoing.

Oliver Cromwell’s house still stands near the cathedral.

With substantial elements from the 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries, Ely Cathedral is an astonishing example of medieval architecture at its finest and a remarkably beautiful building. If you are ever anywhere nearby, I do recommend you go and see it.

Image credits

St Edmund’s chapel (wall paintings): cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Evelyn Simak – geograph.org.uk/p/2168483

Lady Chapel: Photo by DAVID ILIFF. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

All other photographs author’s own.

A word from our sponsor

I post something on this blog a little over once a week on average, but I don’t make a penny out of it. If you enjoy reading the blog, the only thing I ask is that you buy one or more of my books. The cheapest of my books on Kindle costs just 99p. There is information on all my books, with buy links, on this website: http://tomwilliamsauthor.co.uk/my-books/

Sadly, although I seem to average over 3,000 visitors a month, I do not get 3,000 book sales. As I mentioned last week, I am considering putting on an app that allows you to donate if you like the site. Ironically, the app doesn’t take donations as low as 99p and you don’t even get a book out of it, but I suspect that some people might find the idea of a straightforward donation easier than buying a book they may never read. How do you feel about it? If you haven’t said anything yet, can you let me know. Please write in the ‘Comments’ below or use the Contact page on this site.

Thank you.

by TCW | Jul 9, 2019 | Book review

A Plague on Mr Pepys is the second of Deborah Swift’s stories based on the lives of women mentioned in Samuel Pepys diaries. (I reviewed the first in the series HERE.) While Pepys featured heavily in the first book, here he is a more peripheral figure and the story centres on Bess Bagwell, the mistress most often mentioned by Pepys in his diaries. Not a lot is known about her (even her given name comes from Swift’s imagination), which gives Swift free rein to tell a story set amongst the working folk of London. Bess has risen from the whorehouses of Ratcliff to marry a skilled carpenter and be mistress of her own home in Deptford. But life in 17th century London is always precarious and when her husband falls foul of the Guild system and can’t get work in the shipyards, they move rapidly into debt.

This is not a cheerful story. Bess Bagwell’s descent from happily married housewife to debt-ridden homelessness is painfully detailed. Survival in the 17th century depended a lot on family, but families can turn against you if you think you are better than they are and both Bess and her husband have flown too high to rely on the family support that might have saved them.

Bess moves from housewife to working in a glove factory, to taking on piecework and, finally, to unemployment. Somewhere along the way she finds herself trying to save the family finances by trading sexual favours for patronage from Mr Pepys. It seems she hasn’t quite escaped the whorehouse after all.

If things seem bad, there’s still the plague to come. With characters seeming to die on every page, Bess begins to accept that she may well not survive. Worse, it’s not entirely clear that she wants to.

Is there any chance of a happy ending? Well, all things are possible, which is pretty well all that kept me going. It’s a harrowing look at the reality of 17th century life, benefiting from Swift’s considerable expertise in the period. (Sadly this expertise does not extend to naval conflict – an area that I know from experience is all too easy to slip up on. Fortunately most of the story stays firmly on land.) It’s far from an easy read, but with so many novels that romanticise the 17th century, this is a useful antidote – and, if you can stick it – a book that looks long and hard at love, marriage, and family loyalty.

Swift’s writing is fluid and kept me going through difficult subject matter. Even so, this is not an easy book, but one which definitely repays the effort you put into it. Despite the misery, I am happy to recommend it.

by TCW | Jul 5, 2019 | Uncategorized

After a lifetime meaning to visit Ely Cathedral, I finally got around to it this summer. It’s a beautiful place and your admission fee (they have roofs to replace and stonework to maintain) includes the services of some excellent, if not entirely consistent, guides. A lot of what follows comes from them and is no less reliable than many of the stories you read in your history books.

______________________________________________________________________________________

After Hastings in 1066 William did not automatically become ruler of all of England. There was resistance, with local Saxon leaders holding out against him. The North was too far away to be an immediate worry, though Norman armies were eventually to lay waste to much of what is now Yorkshire in what was to be known at the Rape of the North. William’s immediate problem was the South-East and, in particular, a tiresome resistance leader called Hereward the Wake. Hereward would strike from the Fenlands, retreating to the safety of his base at Ely. Ely was then an island surrounded by marshes which provided natural protection against the Norman invaders and winkling Hereward the Wake out was a long and tiresome task. He was the last Saxon leader to be defeated in the south of the country.

When we look at the great Norman cathedrals nowadays we see beautiful monuments built to the glory of God. Of course they were religious buildings, but they had another, arguably more important, purpose. They were the expression in stone of the power of the Norman conqueror. These towering buildings, so much more impressive than the squat Saxon churches they replaced, were a constant reminder to the local Saxons that the Normans were indisputably the new masters of their country. It made sense, then, for the Normans to build one of the earliest and grandest cathedrals in the place where Hereward the Wake had made his last stand. Hence in 1083 they started the building of Ely Cathedral.

Nothing succeeds like success and the grand cathedral became the centre of one of the great monastic institutions of the country. There had already been a Saxon monastery on the site, founded by Queen Ethelreda in 673. Her body was buried at Ely and the cathedral housed her shrine which, under the care of the Benedictines, eventually became a splendid affair supposed to have been covered in silver. So popular did her shrine become that the cathedral was redesigned to facilitate the flow of pilgrims make the East Coast pilgrimage that started at Canterbury and passed through Ely on the way to other towns with a relic and a booming tourist trade further north. Make no mistake about it, tourism and the tourist pound (or groat) was a real thing. The local fairs dedicated to St Ethelreda (Audrey to her friends) were famous for the amount of saint-related tat offered to pilgrims and the junk sold at St Audrey’s fair is thought by some to have given us the word ‘tawdry’.

As Ely’s reputation and its popularity with pilgrims grew, so did its wealth. The buildings were added to until we ended up with this vast and beautiful cathedral standing at the centre of a tiny town – barely more than a good sized village – in the middle of miles of open farmland.

The madness of the cathedral’s isolated position attains truly heroic stature when you realise that it is built on a shallow band of green sand covering a clay sub-soil. The monks obviously didn’t read the bit in the Bible about building on the rock (Matthew 7:24). The result is that every few hundred years significant parts of the building simply collapse – most famously the central spire, which fell in 1322, taking much of the north transept with it. Undeterred, the monks simply decided to rebuild. There were problems, though. The ground that had supported the original spire was clearly unstable, so the monks worked outwards until they came to solid ground. The problem was that this meant the base of the new tower would have to be wider than the old. In the end, the new tower had to have an unsupported span of over 70 feet, posing significant problems for 14th century builders.

They decided to abandon the idea of another spire and to go instead for an octagonal tower. The finished structure was to be 170 feet. Inside the tower is an octagonal lantern made of wood and glass. By ‘wood’ we mean entire oak trunks each weighing ten tons. One of these can be seen in the photo below: the nearest beam to the camera.

Originally the lantern was supported by just eight of these huge oak beams. The additional support in the photo was added in the 18th century when it was discovered that damp had led to some rotting of the original woodwork.

From carpenters’ marks we know the whole lantern was originally assembled at ground level, then broken into its constituent parts, lifted up into the tower and reassembled. The whole thing was built above the very centre of the existing church where the transepts cross the nave. Tower and lantern together weigh over 400 tonnes. It is an astonishing feat of engineering and to this day nobody knows how it was achieved. The lead cladding on the outside of the tower needs replacement and that will be lifted into place by helicopter. Given that Leonardo da Vinci was not to produce his famous sketch of a helicopter for another 150 years it is unlikely that they featured in the builders’ plans.

The effect of the lantern is to allow light to fall directly down onto the crossway at the centre of the cathedral where the monks would have stood to sing at services. Here you see the lantern from below.

The panels below the windows open, possibly to allow monks up in the tower to add their voices to the choir. It would certainly make an amazing soundscape. Here you see one of the panels open, viewed from the other side of the lantern.

And here is the view down into the church, to match the view looking up that we just saw.

The pre-Raphaelite angels date from a Victorian restoration of the cathedral. It’s fashionable to be rude about Victorian restorations, but I think they did a good job here. More about the Victorians next week.

A word from our sponsor

I post something on this blog a little over once a week on average, but I don’t make a penny out of it. If you enjoy reading the blog, the only thing I ask is that you buy one or more of my books. The cheapest of my books on Kindle costs just 99p. There is information on all my books, with buy links, on this website: http://tomwilliamsauthor.co.uk/my-books/

Sadly, although I seem to average over 3,000 visitors a month, I do not get 3,000 book sales. I am considering putting on an app that allows you to donate if you like the site. Ironically, the app doesn’t take donations as low as 99p and you don’t even get a book out of it, but I suspect that some people might find the idea of a straightforward donation easier than buying a book they may never read. How do you feel about it? I’d be honestly glad to know. Please comment below or use the Contact page on this site.

Thank you.