‘The Late Lord’

A blog post about the 2nd Earl of Chatham and the book Jacqueline Reiter wrote about him.

I read an awful lot of books of historical non-fiction. The occasional one is excellent. I read a fair number of contemporary documents about the siege of Cawnpore for my book, Cawnpore, but honestly there was hardly anything that wasn’t included in Andrew Ward’s astonishing Our Bones Are Scattered. It read like a novel too. In fact, I’d recommend it over my own book but at more than 700 pages it’s maybe a bit heavy for a holiday read.

Most of the historical stuff I labour through, though, is beyond awful. I hate saying this, especially when I’ve met some of the authors, but they really can’t write, which is sad seeing that history is essentially about telling stories. (The clue is in the name.)

So let’s hear it for the amazing and amusing Jacqueline Reiter (a clear case of nominative determinism if ever there was one). This is a woman who writes so well that I even read (and mainly enjoyed) her PhD thesis. I haven’t even read my wife’s PhD thesis. (It’s also historical and, in fairness, I’ve read most of it in bits and she is also a brilliant writer – possibly not unconnected to the fact that she didn’t train in history.)

Jacqueline is an excellent speaker, a decent writer of short stories, and publishes an intermittent but stellar blog, but The Late Lord is (as far as I know) her only published book.

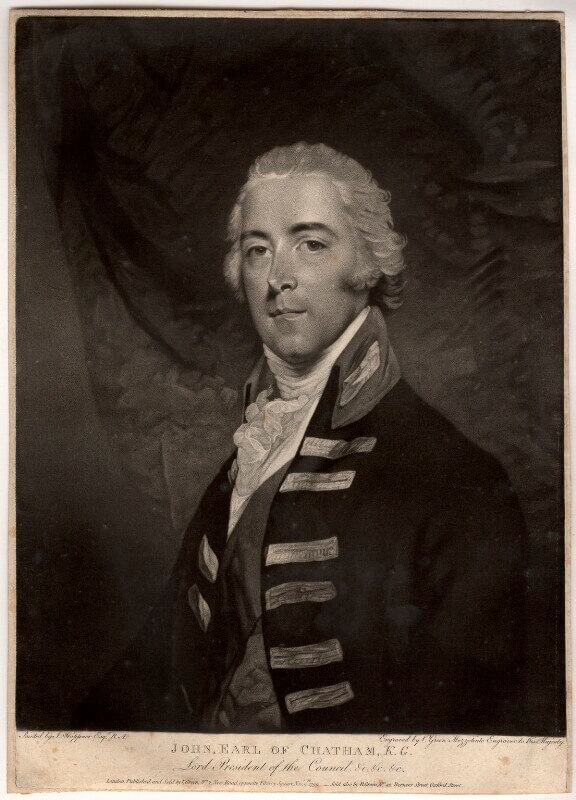

It is a biography of the 2nd Earl of Chatham, the son of the Elder Pitt and the brother of the Younger.

I’ve met people born into a family of over-achievers and it’s a terrible thing to happen to anyone. The poor guy can’t make a speech or hold an opinion without somebody comparing it unfavourably to his father or his brother. Painfully shy to start off with, this drove him to become a virtual recluse, which meant everybody attacking him as a stand-offish snob on top of everything else.

by Valentine Green, after John Hoppner

mezzotint, published 1799

NPG D1282

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The Earl should have hidden away in the country and bred horses, which seems pretty well what he was put on the earth to do, but he had an enormous sense of duty: to his country (which never appreciated him) and to his brother (who knifed him in the back when it became politically convenient). Unable to star in politics and unfitted for a professional career, he took what was traditionally the role of the third son and tried to make a career in the army. He was conscientious and personally quite brave (a key attribute for early 19th-century commanders), being wounded in action. His brother though, saw him as more valuable as political cannon fodder than the traditional sort, so after being wounded he wasn’t allowed to serve in action again until the Younger had ended his political career. At this point, he was given command of a doomed expedition to the Low Countries which was supposed to be a joint naval-military operation. The venture failed spectacularly with the army blaming the navy, the navy blaming the army and the politicians (who bore a significant amount of the responsibility) blaming the most convenient scapegoat, which turned out to be him. Unable to quite believe how completely he was being stitched up, he made a totally inadequate defence and retired in public disgrace.

Failed politician and failed general, the poor man’s main solace was his personal life until his wife went mad and died after a long illness, leaving him distressed beyond measure. At this point the King (as far as I can see his only staunch supporter in his life) made him governor of Gibraltar, in an attempt to give him both an income (it goes without saying that he was broke) and a reason for getting out of bed in the morning (which, as it happens, he very often didn’t do, being a particular enthusiast for long lie-ins).

He hated Gibraltar, but as with almost everything else in his life, he persevered with a sense of duty and was a solidly, if unspectacularly, good governor. The posting, though, broke his health (he was already 65 when he arrived there) and he returned to England after four years. For ten years he lived quietly with his health continuing to deteriorate although, paradoxically, with the man himself away from the public gaze his reputation began to recover. His funeral, after a stroke in 1835, was, Reiter assures us, “in grand style” at Westminster Abbey.

Reiter narrates the Earl’s life with genuine sympathy and makes the politics of the early 19th century much clearer than anybody else I’ve read. She doesn’t condescend to the readers, but neither does she assume knowledge that most amateurs like me will not possess. The book is indexed and annotated to within an inch of its life (possibly more than the non-academic reader really wants) but it remains lively and well written and a thoroughly enjoyable read. If only more history books were written like this, more people would be interested in history.