A taste of India

I’m back from three weeks in India. We went out with an Indian friend who has been talking about us visiting the country together for around 20 years. Finally we all decided that we’re not getting any younger and if we were going to do it, we should do it now.

It was a fantastic experience, visiting her family in Bombay (Mumbai) and then doing the tourist bit: Delhi, Agra, Jaipur and Jodhpur. If you’re not good, I’ll make you look at all of my 500+ photographs.

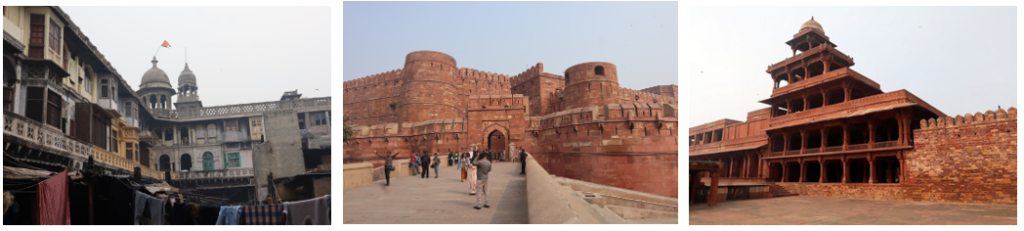

It was lovely to finally see the country that I’d written about back in 2011 with my book, Cawnpore, set during the war of 1857. It was strange writing a book set in a country I had never seen but, of course, the India of 1857 was very different from the India of today. I relied on accounts of the country by Victorian visitors. (I was writing from the viewpoint of a European living there, so the way that people like Fanny Parks saw the country was particularly useful.) We didn’t go to the city that the British knew at the time as Cawnpore. It’s called Kanpur now and almost all traces of the events of 1857 are gone. We did see some of the famous sites from back then: the Red Fort in Delhi and the fort at Agra (just along the river from the Taj Mahal).

In the Red Fort there are the barrack blocks built by the British on the ruins of some of the Moghul palace, which suffered very badly when Delhi was retaken. And in Agra there are the tiny airless rooms built into one of the corridors dating from when the British ran the province from there. There’s the grave of John Russell Colvin, the Lieutenant-Governor of the North-West Province, who died in the fort (of cholera) in 1857 and whose dying wish was to be buried there.

1857 was a long time ago and, certainly for most Indians, hardly a burning source of resentment. If anyone wants to badmouth the British, they are most likely to complain about Partition and the damage that did to their country.

In fact, the way that Indians feel about the British seems conflicted. Staying at the Cricket Club of India in Bombay, or visiting the Yacht Club there, I felt closer to the England of the 1950s than I ever do in London.

Cricket Club of India

Yacht Club

For many Indians, speaking English seems a crucial part of middle-class identity. There are adverts for private schools everywhere and most of these stress that education will be provided in English.

You can see why Prime Minister Modi sees de-colonialisation as unfinished business. Seventy-five years after India achieved independence, he is anxious to see the relationship with Britain defined in a more 21st century context.

Modi (with a white beard) presenting modern India

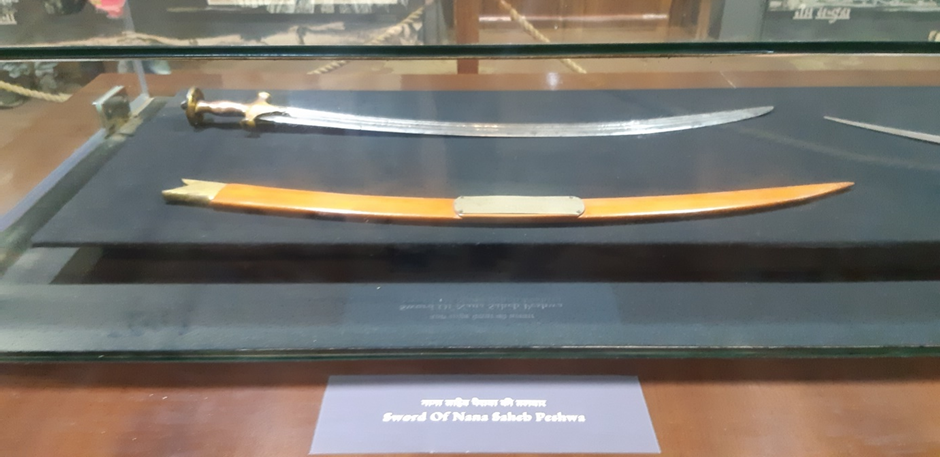

1857 is now celebrated as India’s First War of Independence, with characters like Nana Sahib (who led the Indian forces in Cawnpore) given the sort of uncritical acclaim that the British used to give their military leaders who might, with the wisdom of hindsight, be seen as having had a problematic approach to the way they treated their enemies.

Nana Sahib’s sword on display in the Red Fort

In reality, the events of 1857 were complex. Decades of mismanagement by the British had led to a burning resentment of their rule from many elements in Indian society and, once revolt had broken out amongst soldiers serving the British, it spread to encompass the old rulers of India and ordinary Moslems and Hindus who saw their religion under threat They were joined by people with grudges to settle and many prisoners, released by the mob in the early days of the revolt, who simply saw the chance to profit from the unrest. Violence and massacres by the rebels led to retaliation on an almost unimaginable scale from the British. It is a story from which nobody comes out well, although there was extraordinary courage and heroism demonstrated on both side.

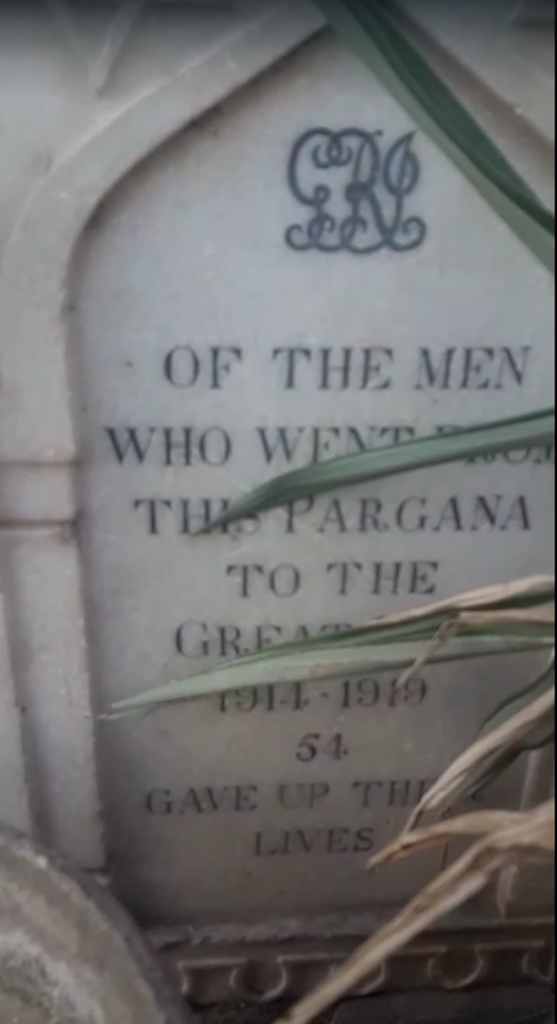

The amazing thing is that after 1857 the British continued to rule in India for almost 100 years. Indians even volunteered in large numbers to defend Britain during the First World War.

Memorial tablet to men from Jodhpur who died in WW1

Indians believed that the British had promised independence if Indians went to fight in France. After the war, with no prospect of independence, Indian attitudes hardened. In response, the British introduced repressive legislation allowing them to imprison independence activists with no proper judicial process. Inevitably the Black Bills (as the legislation came to be known) led to protests and one such peaceful protest resulted in troops firing on an unarmed crowd with hundreds of casualties. (The precise number of dead is unknown.) This event, which came to be known as the Amritsar Massacre, is thought by many to have marked a turning point in the fight for independence.

India finally achieved independence on 15 August 1947.

Cawnpore

Although it has a fraction of the readership of my James Burke series, Cawnpore is the book I am most proud of. It’s told from the point of view of John Williamson, a British official in the East India Company’s administration, running India on behalf of the Crown. Williamson is from a working class background and does not fit in well with the men he works alongside. He is happier making friends in the court of the local Indian ruler and immerses himself in the culture and the language. When war breaks out in 1857, he finds himself caught between two camps. As he tries to find a way out of his dilemma, the war becomes more vicious and the bodies begin to pile up.

It’s a story with no heroes and I can see why it will never be as popular as the straightforwardly swashbuckling adventures of Burke, my Napoleonic Wars hero. Even so, I stand by it as the best thing I’ve written. It’s an absurdly cheap £3.99 on Kindle. I’d be very grateful if you could read it.