Over on Twitter I’ve been joining in with #HistFicMay. It’s a lot of fun and if you are on Twitter yourself you might try having a look at the hashtag. Each day historical novelists are invited to tweet about some aspect of their work. The last few days have been research, an area where the average historical novelist can talk until the most enthusiastic reader has beaten themselves unconscious head butting a wall in the hope that they will stop.

One question was ‘What was the hardest thing to research?’ It’s a beautifully open question. Most difficult fact to track down? Most traumatic? (One person said that researching the slave trade wasn’t a lot of fun and my own research on the English occupation of Ireland left me a bit shaken.)

I’m going to go for ‘Most likely to have you freeze to death in a snowstorm while sheltering in an unheated stone hut 3,000 metres up the Andes.’

It’s a good story and every so often I tried to interest people in it and they completely blank me. Whether this is because they’ve all secretly done something equally daft or whether they can’t believe I’m not making it up, I don’t know. But here goes again.

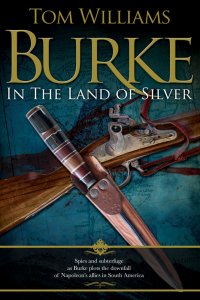

When I was writing ‘Burke in the Land of Silver’ I described him crossing the Andes, which the real James Burke did on his way to spy out the possibilities of a British fleet making a landing on the west coast of South America. Burke misjudged the time to travel and ended up crossing in snow. The account of the trip makes up half a dozen or so pages in the book, but they worried me because I had no idea what crossing the Andes was like in snow. There are accounts of crossing in summer but I felt that the experience at the beginning of winter must be very different. In the end, I decided that the best way to find out would be to do it myself.

Somehow I persuaded my wife (who hates riding) that this would be a good idea.

Burke had made his journey at the beginning of winter but our schedule meant we had to make it in October, in the southern spring, but still snowy in the Andes. We weren’t going to be able to cross down to Chile as the pass was officially still closed, so we couldn’t legally take our horses over. We decided that we would climb to the summit of the pass and turn and come back down.

We were following the route taken by General San Martin, who had crossed the Andes on his way to liberate Chile in 1817. Wisely, he had done it in high summer. When we arrived at our starting point, a ranch outside the city of Mendoza, the rancher who was to guide us up said that he strongly advised against doing it until the weather had improved.

We went ahead anyway. The idea had been to see what it was like for Burke and we found out.

It was cold. Very, very cold.

The road up starts easily enough. People take four wheel drives up there to admire the view. Gradually, though, it gets steeper. Quite a lot steeper.

We rode all day, until we arrived at the only refuge: a stone hut at 3,000 metres.

There were some bed frames and we took the woollen hides from the Western-style saddles and those were our mattresses. We piled any spare clothing on top of our sleeping bags and that was our beds for the night.

It’s not true that there was no heating at all. There are some very dry scrubs growing on the mountain, easily uprooted and carried back to the hut, mainly because they weigh practically nothing.

The good news is that light, dry wood burns very easily. The disadvantage is that the fire lasts hardly any time at all. Still, apart from the smoke blowing back down the chimney, it created a lovely warm spot immediately in front of the fireplace for as long as it lasted.

You could cook on it too.

Water came from a stream that ran past the hut. First thing in the morning, it was covered in ice.

One of the horses decided that a night up there was no fun at all and ran off. Fortunately we had a spare (and the first one was safely waiting for us at a frontier post at the bottom of the mountain when we returned).

Despite the cold, I was stunned by the beauty of the place.

The next day we made a serious attempt to get to the summit of the pass. We almost made it too, but, in the end, the snow defeated us.

It was the coldest I have ever been in my life and I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. I’d love to do it again in the summer (apparently a week after we went the weather changed completely and people travelled up in T-shirts). My wife, though, has vetoed the idea.

And did it make any difference to the book? A few paragraphs may be more convincing.

I thought it was worthwhile anyway.

Now, this is dedication to research!

Not as dedicated as you feeding your children 16th century food! (And eating it yourself when they wouldn’t.)

I’ll bet it made more difference than just a few paragraphs, Tom. It gave you a real taste of Burke’s experience in South America, which may have added flavour, depth and colour to much more than that brief part. Good for you!

Thank you.

Because I love Buenos Aires, I spent a lot of time in the oldest part of the city getting a feel of what it must have been like. There are some streets that give you an idea, I think. I also went out to a hacienda and spent a morning (wish it had been longer) riding with the gauchos while they checked the cattle.

Happy days!