By now I imagine you all know that I’m going to be on a panel at the Malvern Festival of Military History, talking about ‘Turning Historical Fact into Fiction’. My fellow panellists will be:

- Lynn Bryant, who has written novels set in the Peninsular War, as well as historical romances;

- the prolific historical novelist David Donachie;

- Iain Gale who is both a historical novelist and a respected historical writer, especially when it comes to Waterloo;

- and Adrian Goldsworthy, whose speciality is Roman history, but who has also written fiction about Waterloo.

I’m the only one with no academic qualifications in history, presumably there to explain how a rank amateur handles these things.

As you will know from the piece I posted a couple of weeks ago, I take historical research seriously, if not as seriously as some other writers. But what on earth made me, as a non-historian, want to write historical novels in the first place and how do I approach the whole issue of researching them?

Find something that interests you

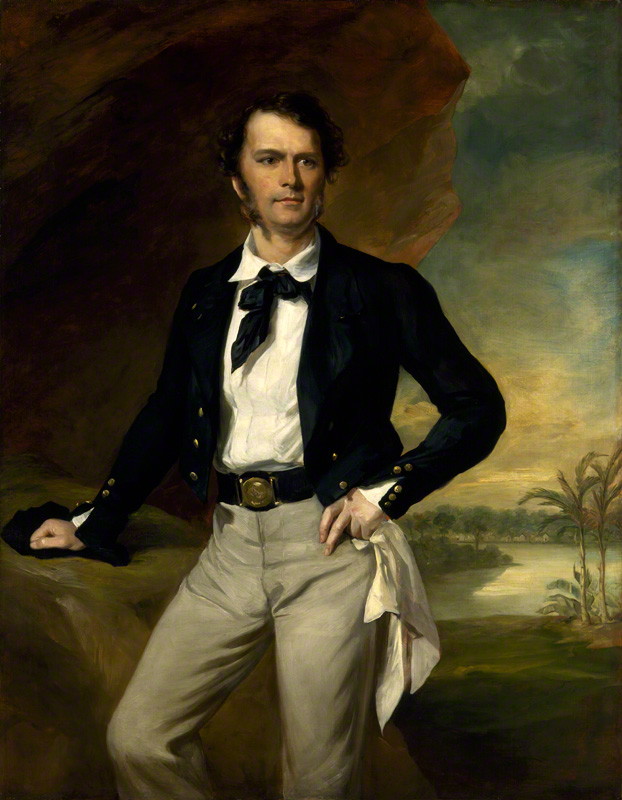

My interest in writing did not start with history. My first book, The White Rajah, was an attempt to show why good men, with good intentions, can end up doing terrible things. I wanted to write a book about somebody who arrives at country in conflict and who, in trying to resolve the situation, ends up committing a terrible war crime. When I tried to think of a scenario where this might happen, I realised that I already had one. Years earlier I had become fascinated by the life of James Brooke of Sarawak — a man whose efforts to rid the country of pirates resulted in a massacre so terrible that, even in the mid-19th century, it resulted in public protest in Britain and questions in Parliament.

James Brooke by Sir Francis Grant,1847

Researching this was not a problem. I had wanted to write a book about Brooke when I first grew interested in him and I had done intensive research, back in the days when that meant sitting in real physical libraries, reading his diaries and the autobiographies of people he had worked with. I even got as far as working on a book which attracted enough attention for me to be given an editor who suggested that the amount of factual detail in it was better suited to a biography than to a novel.

Keep it simple

I learned a valuable lesson from that experience. Too much attention to historical detail can get in the way of storytelling. Every time Brooke sailed up a river, whether he took the left branch or the right was carefully based all that research. That didn’t half wreck any flow there might have been in my writing! When I came back to the idea of a book about Brooke (working title, inevitably, ‘The Brooke Book’), I deliberately did not reread all my notes. When it was finished, I checked the historical facts and was pleased to discover that there weren’t that many errors. Where there were, what my memory had done (as memory generally does) was to blur detail and simplify things. That, it seems to me, was exactly what I wanted.

A historical novel should be simple to follow. If there are two very similar battles, take the best bits of both and present them as a single battle and forget the other. In Burke in the Land of Silver I take out a whole invasion. As I say in the historical note (and if you are going to change things like that, a historical note is really important) readers are not going to believe that the fiasco of Britain’s 1806 invasion of Buenos Aires was almost exactly repeated just a year later. And even if they did believe it, it would be boring.

A historical novel also needs to keep up some sort of momentum. At the end of The White Rajah, Brooke’s activities are the subject of an official enquiry by the British. Brooke travelled to Singapore to give evidence justifying his position and the enquiry is, in a way, the moral climax of the book. In my story, Brooke waits in Singapore until the enquiry reports that he has been exonerated. In fact, he returned to Borneo and waited months for the report to be produced. There’s no drama in that – no sense of relief when, finally, he is told that, in the eyes of the British authorities at least, he had done nothing wrong. In my book, he waits in Singapore. A few weeks later, he is there in person when the Inquiry’s finding are presented. That’s complete fiction. The findings, though, are accurately reported. That’s the bargain that, in my view, the writer makes with the historian.

Read proper historians – that’s what they’re for

As I am not a historian, I do not make any pretence at doing original research for my books (although I have been seeing wandering the streets of Buenos Aires making notes on the architecture or reading court documents at the National Archives in Kew). There are writers whose efforts are backed up by significant amounts of original research, but that’s a different sort of novel. I am there to tell a tale, not to probe too deeply into the details of the past. Fortunately there are historians who have done most of the research for me. Once something has seized my interest and sown the seeds of the ideas for a new book, I will generally start by reading a basic overview of the history written by a professional historian. In the case of Cawnpore, for example, I started with Andrew Ward’s brilliant account, Our Bones are Scattered. I then turn to contemporary accounts for details that I can work into my plot. Although it’s a bonus to be able to visit Borneo or Argentina before writing, it’s not essential. An Indian friend assures me that Cawnpore works well enough for them to ask why I haven’t got an Indian publisher, although I have never been to India in my life.

National Archives, Kew

National Archives, Kew

Being a historian does bring advantages. It’s certainly easier to write about a period that you are already very familiar with. Interestingly, though, many historians end up writing books set in periods other than the one that they studied. As my wife has done postgraduate historical research, I am happy to believe her when she says that a detailed knowledge of the welfare system in the 1940s does not help at all in writing about cavalry formations in 1815. Interestingly, I find the most useful insights into 19th-century military life come, not from history at all, but from my son’s 21st-century military experiences. Accounts of 19th-century soldiering suggest that the attitudes of the average squaddie have changed less than one might think in 200 years.

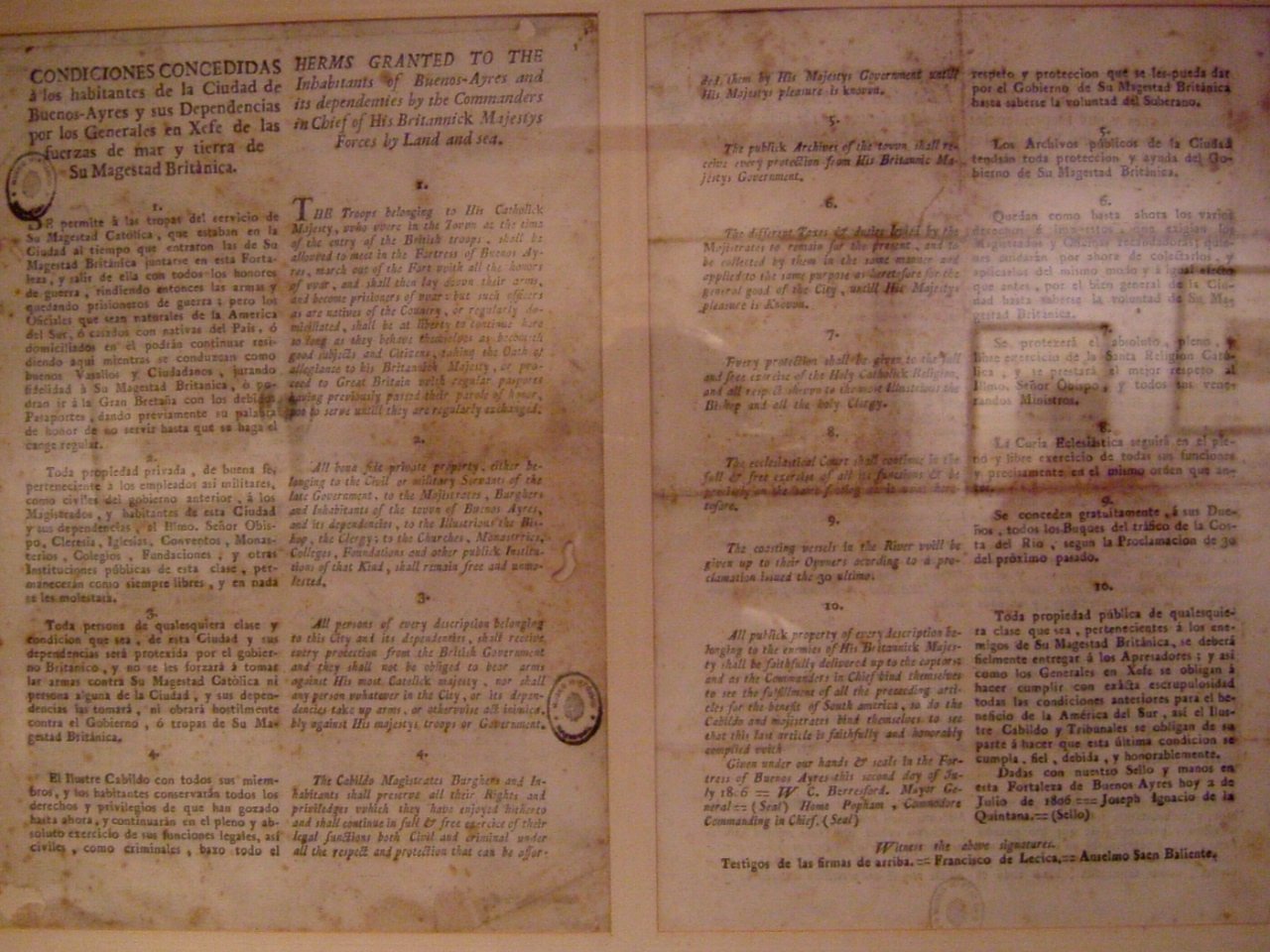

Notice by British Occupying Forces, Buenos Aires, 1806

Notice by British Occupying Forces, Buenos Aires, 1806

So here I am, about to talk as a dilettante in a room full of historical experts. Am I nervous? Yes, I am a bit. But I’m not embarrassed about what I do. My books use historical stories to look at issues of today. Cawnpore was written when my son was serving in Afghanistan and there are aspects of the British occupation of India that might usefully have been remembered before we entered that war. Burke in the Land of Silver has the British invading a country in order to liberate it. In a Buenos Aires museum I read the proclamation assuring the people that we were freeing them from Spanish tyranny. The parallels with Iraq were horribly clear.

Historical fiction lets me tell stories that are relevant to today. I always try to be true to the historical record, but history must be the servant of my story, not its master. I’m looking forward to seeing how the other panellists walk the tightrope between historical fact and historical fiction.

Greatly enjoyed this. Allays my own questions too. Do I detect a fellow Flashman enthusiast too? Would happily take your next class in sucking eggs. Where do I sign up?

Thanks for this. Yes, I’m a huge Flashman fan.

If you can get to Malvern the weekend after next, you will get the benefit of the experience of my fellow panellists. I don’t think there’s anything earlier than Agincourt on the programme, but you might find something that interests you.

Today’s blog is a follow-up to this post talking about the importance of Historical Notes: http://tomwilliamsauthor.co.uk/historical-notes/

Tom, if you tell it like you have here, you will be received most warmly, I am sure! This is such a good article, and one I will keep to re-read if I ever do write histfic (I am scared to!). It reminds me of Carol Hedges’ advice – write the story and the people, not the history, or something like that.

Thank you.

How much you can let your characters take over depends, of course, on what sort of historical incidents they are caught up in. In ‘Back Home’ I had a pretty free hand because the history was just the background to the action. In ‘Cawnpore’, by contrast, there is so much historical detail available about the siege that I had to move my main character within very tight historical parameters. Almost everything that happens to him during the siege is defined by the actual historical events. Although I imagine that most readers wouldn’t care if he arrived somewhere a day or two before history says that he possibly could have, I’d know and it would worry me.

The most blatant cheat I’ve done is when I wanted one of my characters to be Madrid for the uprising against the French (during ‘Burke in the Land of Silver’) and the historical character simply couldn’t have made it there on that day. It was too good an incident to miss, and nobody is going to know exactly where my character really was on a particular day unless they’ve done quite a lot of research, so I lied. I did admit to it in an endnote though.

Research and then don’t bog the story down with all you’ve learned. Yes, that’s the key. You are correct!

Thank you.

Very sound sense here! Should be read – and taken to heart – by any aspiring, or even practicing, historical novelist!

Thank you.