There has been a huge amount of interest in my post on cavalry at Waterloo, so I’m going to briefly revisit it.

It was during the charge of the Scots Greys that the French lost one of their regimental colours. Losing your colours was a very big deal – captured colours were listed in battle reports alongside the number of enemy dead and the number of their cannons you had captured. To lose your regimental colours was a huge disgrace and the colours would be entrusted to a junior officer supported by some of the biggest and strongest men in the regiment who acted as bodyguards. French colours were referred to as ‘Eagles’ from the gilded eagle that topped the staff that carried the flag. Eagles were awarded to regiments by Napoleon personally.

Sergeant Ewart was, by all accounts a big man and a noted swordsman. He was carried along by the charge and found himself closing on the colours. He cut down the standard bearer and two bodyguards, writing later, “I had a hard contest for it.” His commander ordered him to the rear, carrying the Eagle off as a trophy.

Sergeant Ewart was later promoted to Ensign because of his valour at Waterloo. An Ensign is the most junior officer but this was at a time when it was rare to rise from the ranks.

The Eagle (with its ‘45’ indicating that it belonged to the 45th Regiment of the Line) is now in the regimental museum of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards in Edinburgh Castle, as is the standard of the regiment with its battle honours embroidered on it.

The Royal Scots Greys incorporated the Eagle into their cap badge and their successor regiment, the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards wears the eagle and the battle honour ‘Waterloo’ to this day.

Ewart’s capture of the Eagle caught the public imagination and is the triumph that everybody remembers today, but that was not the only Eagle captured at Waterloo. The Royal Regiment of Dragoons (like the Scots Greys, part of the Union Brigade) captured the standard of the 105th. One reason that this made less impact is probably that there was an acrimonious argument about who actually captured it, which took some of the gloss off the achievement. The credit was given to Corporal Stiles (or Styles) who returned to the Allied lines with the flag, but Capt Alexander Clark claimed that it was he who had struck down the officer carrying the flag and that he had then ordered Stiles to take it from the field. Another officer later claimed that it was actually him who had captured the flag, though this claim, made very late in the day, is generally disregarded. After enquiries made by the regiment, Stiles was given official credit for the action, a decision which Clark disputed for the rest of his life. It seems that in the heat of the action, with both men close to the standard and struggling to take it from the bearer, no one will ever be quite sure what happened. It’s a good example of why people who claim to be certain of anything that happened in the heat of battle are deluding themselves.

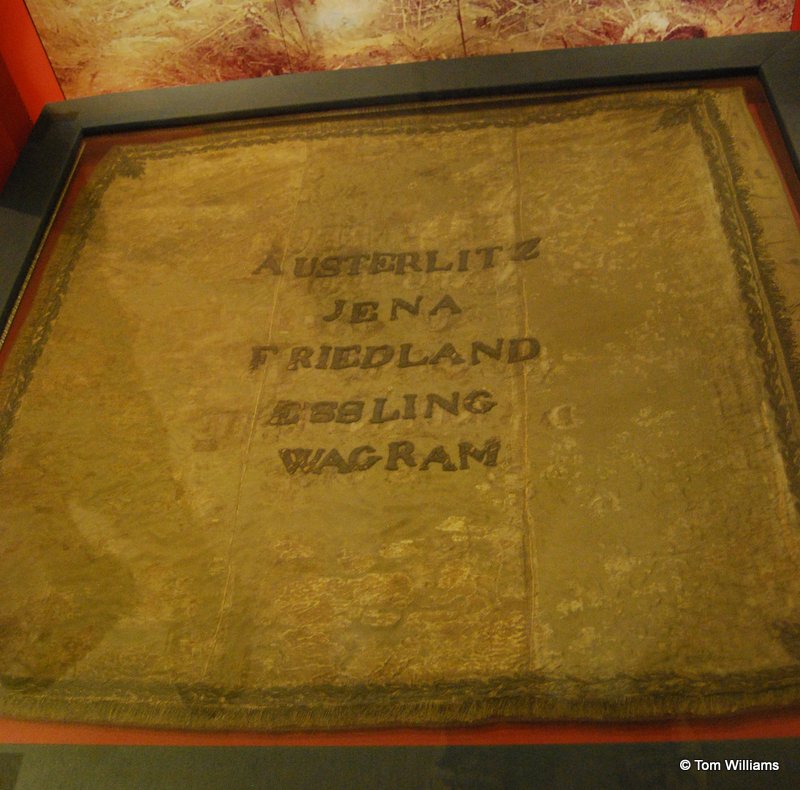

Standard of the 105th (National Army Museum)

Standard of the 105th (National Army Museum)

Stiles, as a mere corporal, was promoted as a result of the capture. Like Ewart he ended his career as an Ensign, but in a West India Regiment (not a particularly desirable posting). Clark, on the other hand, ended up as colonel of the Scots Greys.

Malvern Festival of Military History

Waterloo will feature at the Malvern Festival of Military History with talks on Napoleon and on the battle on the final day, Sunday 7 October. I’m appearing on the same day, talking about turning historical fact into fiction. The festival looks to be an exciting three days with talks on everything from Agincourt to Vietnam. Tickets are still available.

Not in the Royal Scots museum they are a different Regiment The Eagle is in the Royal Scots Drogoon Gaurds museum in Edinburgh Castle

I have corrected this. I apologise but, having visited the museum and thinking I was paying reasonable attention, you must admit it’s an easy mistake for a civilian to make.