After a lifetime meaning to visit Ely Cathedral, I finally got around to it this summer. It’s a beautiful place and your admission fee (they have roofs to replace and stonework to maintain) includes the services of some excellent, if not entirely consistent, guides. A lot of what follows comes from them and is no less reliable than many of the stories you read in your history books.

______________________________________________________________________________________

After Hastings in 1066 William did not automatically become ruler of all of England. There was resistance, with local Saxon leaders holding out against him. The North was too far away to be an immediate worry, though Norman armies were eventually to lay waste to much of what is now Yorkshire in what was to be known at the Rape of the North. William’s immediate problem was the South-East and, in particular, a tiresome resistance leader called Hereward the Wake. Hereward would strike from the Fenlands, retreating to the safety of his base at Ely. Ely was then an island surrounded by marshes which provided natural protection against the Norman invaders and winkling Hereward the Wake out was a long and tiresome task. He was the last Saxon leader to be defeated in the south of the country.

When we look at the great Norman cathedrals nowadays we see beautiful monuments built to the glory of God. Of course they were religious buildings, but they had another, arguably more important, purpose. They were the expression in stone of the power of the Norman conqueror. These towering buildings, so much more impressive than the squat Saxon churches they replaced, were a constant reminder to the local Saxons that the Normans were indisputably the new masters of their country. It made sense, then, for the Normans to build one of the earliest and grandest cathedrals in the place where Hereward the Wake had made his last stand. Hence in 1083 they started the building of Ely Cathedral.

Nothing succeeds like success and the grand cathedral became the centre of one of the great monastic institutions of the country. There had already been a Saxon monastery on the site, founded by Queen Ethelreda in 673. Her body was buried at Ely and the cathedral housed her shrine which, under the care of the Benedictines, eventually became a splendid affair supposed to have been covered in silver. So popular did her shrine become that the cathedral was redesigned to facilitate the flow of pilgrims make the East Coast pilgrimage that started at Canterbury and passed through Ely on the way to other towns with a relic and a booming tourist trade further north. Make no mistake about it, tourism and the tourist pound (or groat) was a real thing. The local fairs dedicated to St Ethelreda (Audrey to her friends) were famous for the amount of saint-related tat offered to pilgrims and the junk sold at St Audrey’s fair is thought by some to have given us the word ‘tawdry’.

As Ely’s reputation and its popularity with pilgrims grew, so did its wealth. The buildings were added to until we ended up with this vast and beautiful cathedral standing at the centre of a tiny town – barely more than a good sized village – in the middle of miles of open farmland.

The madness of the cathedral’s isolated position attains truly heroic stature when you realise that it is built on a shallow band of green sand covering a clay sub-soil. The monks obviously didn’t read the bit in the Bible about building on the rock (Matthew 7:24). The result is that every few hundred years significant parts of the building simply collapse – most famously the central spire, which fell in 1322, taking much of the north transept with it. Undeterred, the monks simply decided to rebuild. There were problems, though. The ground that had supported the original spire was clearly unstable, so the monks worked outwards until they came to solid ground. The problem was that this meant the base of the new tower would have to be wider than the old. In the end, the new tower had to have an unsupported span of over 70 feet, posing significant problems for 14th century builders.

They decided to abandon the idea of another spire and to go instead for an octagonal tower. The finished structure was to be 170 feet. Inside the tower is an octagonal lantern made of wood and glass. By ‘wood’ we mean entire oak trunks each weighing ten tons. One of these can be seen in the photo below: the nearest beam to the camera.

Originally the lantern was supported by just eight of these huge oak beams. The additional support in the photo was added in the 18th century when it was discovered that damp had led to some rotting of the original woodwork.

From carpenters’ marks we know the whole lantern was originally assembled at ground level, then broken into its constituent parts, lifted up into the tower and reassembled. The whole thing was built above the very centre of the existing church where the transepts cross the nave. Tower and lantern together weigh over 400 tonnes. It is an astonishing feat of engineering and to this day nobody knows how it was achieved. The lead cladding on the outside of the tower needs replacement and that will be lifted into place by helicopter. Given that Leonardo da Vinci was not to produce his famous sketch of a helicopter for another 150 years it is unlikely that they featured in the builders’ plans.

The effect of the lantern is to allow light to fall directly down onto the crossway at the centre of the cathedral where the monks would have stood to sing at services. Here you see the lantern from below.

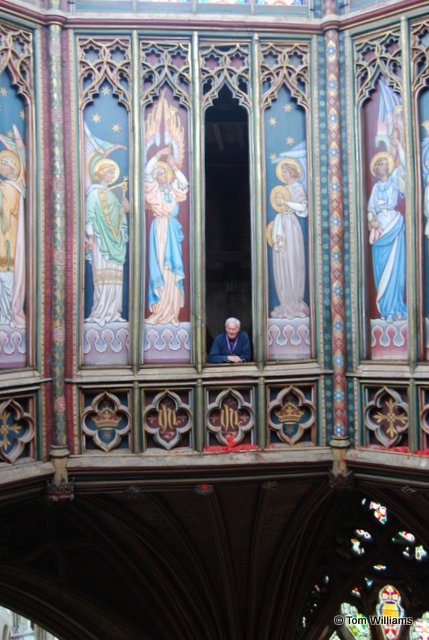

The panels below the windows open, possibly to allow monks up in the tower to add their voices to the choir. It would certainly make an amazing soundscape. Here you see one of the panels open, viewed from the other side of the lantern.

And here is the view down into the church, to match the view looking up that we just saw.

The pre-Raphaelite angels date from a Victorian restoration of the cathedral. It’s fashionable to be rude about Victorian restorations, but I think they did a good job here. More about the Victorians next week.

A word from our sponsor

I post something on this blog a little over once a week on average, but I don’t make a penny out of it. If you enjoy reading the blog, the only thing I ask is that you buy one or more of my books. The cheapest of my books on Kindle costs just 99p. There is information on all my books, with buy links, on this website: http://tomwilliamsauthor.co.uk/my-books/

Sadly, although I seem to average over 3,000 visitors a month, I do not get 3,000 book sales. I am considering putting on an app that allows you to donate if you like the site. Ironically, the app doesn’t take donations as low as 99p and you don’t even get a book out of it, but I suspect that some people might find the idea of a straightforward donation easier than buying a book they may never read. How do you feel about it? I’d be honestly glad to know. Please comment below or use the Contact page on this site.

Thank you.

I’d try the BuyMeACoffee.com … It’s worth a shot anyway. And, doesn’t take much time to set up and add to each post before you send it out. I’ve not had anyone buy me a cup of coffee from the main/home page; but have from the blog article itself. The buy me a coffee link seems to be more effective than a straight donate (through paypal) button. 🙂 🙂

Thanks for this. I really appreciate you taking the trouble to comment. I’m going to see if there are any other comments and then may well give it a go.

When I was at Cambridge University in the mid ’70s my Structures Professor was a consultant to Ely Cathedral. At that time they put a reinforced concrete ring beam into the tower. It had to have a design life of 500 years so the reinforcement was stainless steel.

Fascinating. Is this the main west tower? I didn’t go up that one.