by TCW | May 10, 2019 | Indian history

I generally post on this blog on Fridays and this particular Friday is the exact anniversary of the events at the Meerut in the North West Provinces of India (now Uttar Pradesh) which sparked a rebellion that shook the British Empire and changed the history of India. This seems worth marking with a post about the events of 1857. I did post an earlier version of this a year ago, but I have more readers nowadays and I hope I will be forgiven for repeating it.

The army of the East India Company – the peculiar organisation responsible for European rule in the sub-continent – had recently introduced Enfield rifles with cartridges said to be greased with pig and beef fat. As the paper on the cartridges was torn off with the teeth when the rifle was loaded (‘biting the bullet’) their use was anathema to both Muslims and Hindus. Most commanding officers held off issuing the new cartridges, waiting for the unrest to calm down. Unfortunately, Colonel Carmichael-Smyth was not most officers. He ordered some of his troops to drill with the new cartridges and, when they refused, they were paraded in front of the rest of the regiment, sentenced to life imprisonment and marched off in chains. This was on 9 May 1857.

Nowadays we tend to see the events at Meerut as marking a violent break with the past by the sepoys (native soldiers). In fact, mutinies were not uncommon. Generally the approach of the military authorities was to try to handle them as smoothly and calmly as possible and they had no significant impact. Perhaps things at Meerut would have got out of hand anyway, given the deteriorating relations between Indians and Europeans at the time, But it seems likely that most of the problems were the result of gross stupidity by Colonel Carmichael-Smyth. (A young European officer in Carmichael-Smyth’s regiment wrote to his mother on 10 May – shortly before becoming one of the first Europeans to die – “It is generally supposed that [Carmicael-Smyth] will lose his command.”)

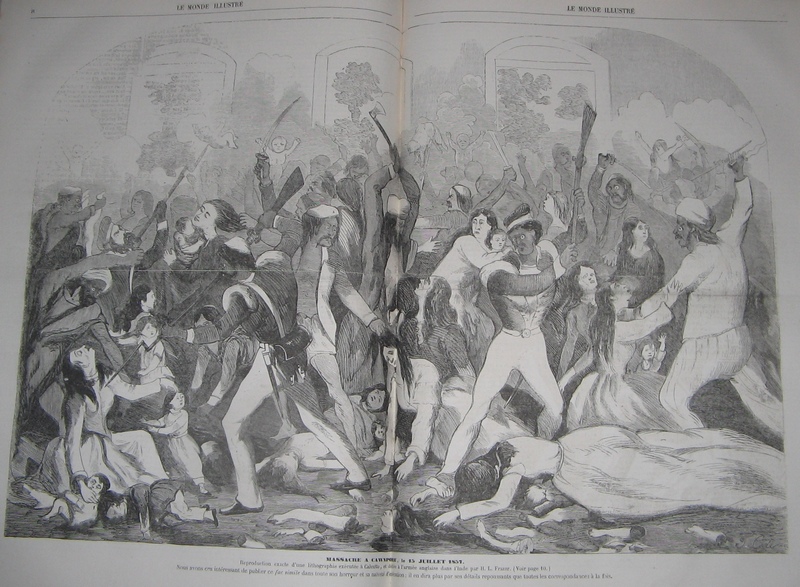

On 10 May the Indian troops rose in revolt, released the prisoners, burned the camp and killed about fifty European men, women and children before setting off to march to Delhi. The Indian Mutiny (or First War of Independence) had begun.

Nobody knows if the rumours were true. Even today there is doubt about what the cartridges were actually greased with. In any case, the Mutiny was not really about the fat on the cartridges. Trouble had been brewing for a while and the incident at Meerut simply served as the flash point for a revolt that many people had been expecting for some time. The Indians had become increasingly uncomfortable under British rule. The old, relaxed style of colonial government by men who had come to love India and worked alongside existing Indian customs and institutions was giving way to a more ‘modern’ approach. Christian missionaries were attacking Indian beliefs; the caste rules that governed Indian soldiers were being disregarded by European officers; Indian land was being seized on dubious legal grounds. In a word, the British, no longer captivated by India, were becoming arrogant.

Arrogance is a dangerous emotion when your army relies on the services of the very people whose culture and customs you are dismissing as uncivilised.

“The Sepoy revolt at Meerut,” from the Illustrated London News, 1857

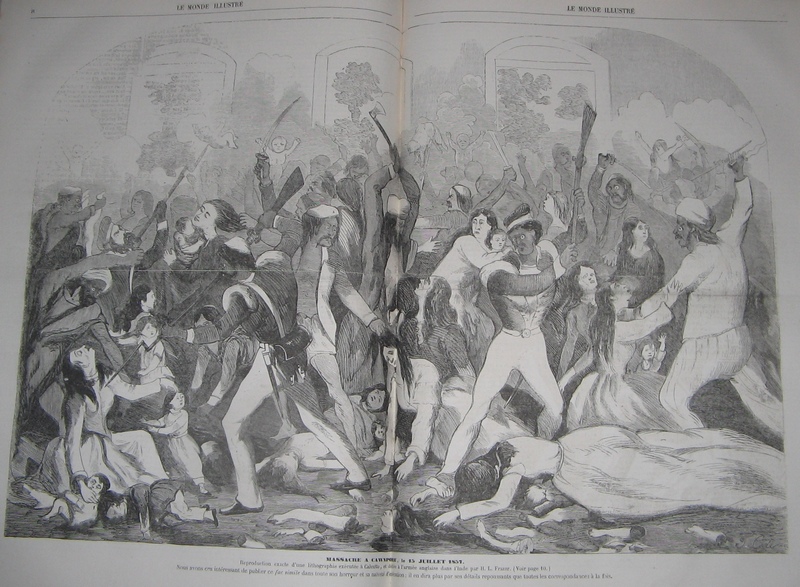

The events at Meerut triggered a war of extreme savagery. Both sides killed without mercy and often with little distinction between combatants and non-combatants. Some Indians sided with the British, fighting against other Indians. Many officers were convinced that their men would remain loyal and literally trusted them with their lives. Sometimes that trust was rewarded, sometimes they were summarily shot.

The unrest led to much violence within the Indian community. Old scores were settled and Indians who had become rich under British rule were often denounced and murdered, their property looted.

Some British officers opened fire on men who were almost certainly loyal to them, forcing them to join the enemy. Some Indian princes changed sides, fighting for Europeans or rebels, depending on how the tide of battle changed.

It was against this background of bloodshed and treachery that I set the story of Cawnpore.

Cawnpore (now Kanpur) lay on the Ganges, about 250 miles from Meerut. The local ruler, Nana Sahib, was regarded as friendly to the British and, even after news of the Mutiny reached the town, the local British commander, General Wheeler, did not expect any trouble. As tensions grew, Wheeler made provision for the British to shelter around two hospital blocks in the British lines, building a low earth wall around them. This, though, was simply a position to wait out any local unrest – it was never seriously designed as a defensible fort.

When Nana Sahib decided to join with the rebels, Wheeler found himself trapped with around sixty European artillery men with six guns, eighty-four infantrymen, and about two hundred unattached officers and civilians and forty musicians from the native regiments. In addition, he had seventy invalids who were convalescing in the barracks hospital and around three hundred and seventy-five women and children.

The siege of Wheeler’s entrenchment became a tale of astonishing heroism and fortitude and it is central to the story I tell, but Cawnpore, for all the military trimmings, is not essentially a war story. My hero (insofar as he is a hero) is John Williamson, the narrator of The White Rajah. His life in the Far East has left him more comfortable with the princelings of the local Indian court than with the class-ridden Europeans he works with. He has friends on both sides of the conflict and struggles to stay true to them all. In the midst of a war that is fought with terrible ruthlessness, he tries to remain a decent person.

Cawnpore is a story about idealism and reality; about belonging and exclusion. It looks at the British colonial project and how it went so horribly wrong. It makes most people cry.

At the time that I wrote it, my son was serving in Afghanistan, in a conflict that can trace its origins back to the 1850s and before. Yet again, British troops were fighting and dying for a way of life they didn’t understand. Researching Cawnpore made me realise that the important thing about the war in Afghanistan wasn’t that it was right or that it was wrong: it was that it was futile.

Cawnpore is my favourite of all the books I’ve written. I do hope you read it.

Reference

Cadell, P. (1955). THE OUTBREAK OF THE INDIAN MUTINY. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 33(135), 118-122.

by TCW | Jan 25, 2019 | Indian history

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about Nana Sahib, “the demon of Cawnpore”. I suggested there that the rights and wrongs of his behaviour (and that of the British) were not as straightforward as they are often presented. Even so, when Heather Campbell of The Maiden’s Court invited me to write the story from Nana Sahib’s point of view, it was a serious challenge. After all, how do you set about justifying a war crime?

In the end, I was pleased with what I wrote and I thought I’d like to share it here. I know that a lot of people who read this blog are interested in writing and I do recommend things like this as useful exercises. And for those who don’t write, I hope you can just enjoy it as a different way of looking at an infamous bit of Indian history.

Nana Sahib’s story

My father was the Peshwa of the Maratha Empire. He was a mighty lord who rose against the British who had come into his country and despoiled it. He fought valiantly against the invaders, but he was defeated and exiled from his own country to the miserable little village of Bithur, not far from Cawnpore. The British allowed him to retain his title and a small pension and he made his peace with them and lived alongside his enemy until he died in 1851.

I was an adopted son – a common practice in my country when a great lord has no sons of his own – but the British refused to recognise me as Peshwa and no longer paid the pension that they had paid to my father.

Despite the loss of my lands, my title and my pension, I tried to be a good friend to the British. They had ruled in India now for a hundred years and many Indians had accommodated to them. But their rule was becoming more harsh. Where once they had made honourable peace with men like my father, now they seized their lands, ignored their titles, and denied them the respect they were due in their own country. They began to send Christian missionaries who tried to tempt my people from their faith. They told us we must abandon our old customs.

Those Indians who served in their armies (for there is no disgrace in serving the army of any lord once he has proved himself a power in the land) were not accorded the respect they had been. Their officers, who had once loved this country, were replaced by arrogant fools who did not understand our ways. There were rumours that they might be sent overseas, where they would lose their caste. Then there was the terrible business of the new cartridges. The cartridges were greased with the fat of cattle and with the fat of pigs. This was an insult to all the Hindus in the Army and to their brothers who were Moslems.

Finally, the people of India rose up against these injustices. I was not sure what to do. I had been friends with the British and I hoped that things could be settled without violence, but it was soon apparent that there must be a war and that the British would finally be driven from our country. My people looked to me, for they still called me “Peshwa” and acknowledged me as their leader. Now that it had come to war, it was my duty to lead my people against the British in Cawnpore.

The British fought bravely: I will give them that. Hundreds of my troops died as we attacked their fort again and again. In the end, I agreed to lift the siege if they would go. They said they would and asked for boats to sail down the Ganges to rejoin their people. But this had to be a trick. The British were being defeated everywhere. Where could they hope to go? No, once they were on the boats they could set up a fort somewhere else and attack us from there. My generals told me I would be stupid to let this happen.

What was I to do? They had surrendered, but there was nowhere they could go. We had an army in our midst that could turn on us at any time. The British, we Indians had learned over the past hundred years, were liars. They had promised my father he could keep his title and then took it from me because I was adopted: a cheap trick. They had stolen the Kingdom of Oudh on the same pretence – that the new King was adopted, and therefore could not inherit. We could not trust them.

My general, Tatya Tope, told me what to do. He arranged to have artillery hidden across the river from the boats and for his men to conceal themselves along the banks. When the British came to the boats, we opened fire. They still had their muskets. It was war: these things happen. We tried not to kill the women and children, but we took them captive and kept them safe.

Then news came that a British force was on its way to relieve the siege. Everybody was terrified. The British were killing people who they thought might have ever harmed any of their troops and they would kill us all if they heard what had happened by the river. It was essential that any of the British who might speak against my sad, but necessary, actions should be silenced. I had no choice: the women and children would speak against me. They had to die. So many Indians had died under British rule and the British always said that sometimes these things were necessary or that sometimes these things just happened. But would they have happened if the British had not stolen our country? Had we asked these women and children to come and live amongst us, ordering their Indian servants to do this and to do that as if they were slaves? Bringing their foreign ways, their terrible food, their arrogance and their ignorance? They looked down on us as savages and sneered at our ways. Well, they’re not sneering now.

The British beat us in 1857. I was driven into exile and watched as the white men tightened their grip on my country. But I know that our time will come. It is not right that the Indians should live under the rule of the British and one day we will rise up and we will defeat them and I will not be hated by the rulers of India, but loved by them as one of those who showed the way to regaining our own country.

Cawnpore

The story of Cawnpore and the clash of cultures that led to the massacre is the subject of my book, Cawnpore. The narrator is English, but in love with an Indian. Caught between the two camps, he sees the tragedy developing around him, but is powerless to stop it. Can he survive the massacre and, if he does, can he save anyone else from the horror?

Cawnpore is the second of my books about John Williamson but it stands alone. Of the three, it is my personal favourite.

Cawnpore is available on Kindle and in paperback. It has had some lovely reviews.

“All that historical fiction should be: absorbing, believable and educational.” – Terry Tyler in Terry Tyler Book Reviews

“For anyone who has a love for this period, Cawnpore is probably one for you.” Historical Novel Society

If you haven’t already, I do hope you will buy it soon.

by TCW | Jan 11, 2019 | Indian history

Just before Christmas I had a request from Lydia from Toronto (sounds like I’m writing a problem page). She asked for more posts about the people who were caught up in the historical events I describe. Given the interest there’s been in the item about Indian history that I just revived from my old blog-site (you were fun, Blogger, but life moves on) I suggested I might dig out something I wrote about Nana Sahib, one of the key characters in the siege of Cawnpore, as featured in my book, Cawnpore. Lydia was happy with that, and fortunately I’ve come across some more details of the end of his life since my original post, so here goes:

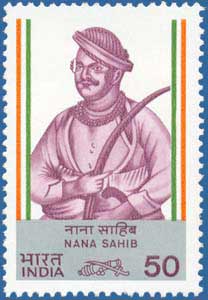

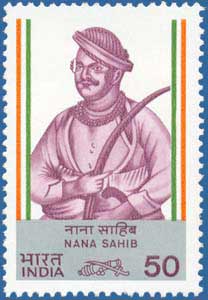

‘Real’ historians tell stories pretty much as much as historical novelists do and, when I was young, the story that was told about Cawnpore had a clear villain: Nana Sahib.

Nana Sahib was, according to the Victorians (and it is their version of the Mutiny that dominated the way it was seen for a hundred years), the evil genius of Cawnpore. He was the local Indian prince who pretended sympathy for the British, and then betrayed them. Most importantly, he was the man who ordered the massacre there. For decades, he was hunted by the British, who wanted to drag him before their courts and, after a show trial, execute him. But he vanished after the British recaptured Cawnpore. For decades, there were claimed sightings of the man, but eventually it was presumed that he was dead and, in time, the historical character was forgotten and only the pantomime villain of Cawnpore lived on.

I believe that Nana Sahib was a much more complex and sympathetic character than he is usually painted, and I have tried to reflect this in my book.

Seereek Dhoondoo Punth was born in 1824 into an undistinguished family, but was adopted by Baji Rao, the Peshwa of the Maratha Empire. His capital was at Poona (now Pune), which was one of the main political centres of India. From there, he ruled over the most important of the Indian kingdoms.

The Maratha Empire was riven by internal strife and some factions went to war against the British. There were three wars in total and, after the third, the British decided to annex the Maratha Empire. Baji Rao was allowed to keep his title and even given a pension by the British. However, he was stripped of all political power and forced into exile. He chose to live in Bithur (now Bithoor), a small town near Cawnpore (now Kanpur).

Baji Rao needed a male heir to succeed him and, in the absence of a natural heir, Nana Sahib was adopted in 1827 and raised to inherit his father’s position. This was a common practice in India when a ruler did not have a male heir. The British, however, refused to acknowledge that an adopted son could inherit a hereditary title and would not acknowledge him as Peshwa. By then, the title was purely honorary and it is possible that the British did not realise how much distress this caused, although Nana Sahib petitioned repeatedly for his title to be recognised. He also petitioned that the pension that was paid to his father should continue to be paid to his father’s heirs, but the British refused to do this, claiming that the pension had been personal to Baji Rao and their obligation had died with him.

Nana Sahib toyed with the idea of travelling to England to appeal directly to the East India Company but, as a Brahmin, he would have lost caste by travelling overseas. He therefore sent Azimullah Khan, one of his most trusted advisers. Azimullah Khan appears to have enjoyed his trip, especially as he was something of a ladies’ man and was a great success with many of the women he met in London. However, he was completely unsuccessful in pleading Nana Sahib’s cause and the experience seems to have left him with a very strong antipathy for the British.

Despite Azimullah Khan’s attitude to the British and Nana Sahib’s grievances against them, the Peshwa enjoyed the company of Europeans and was very fond of entertaining them, occasionally arranging parties in the European style at his palace, Saturday House, at Bithur. His generosity made him a popular figure with the English who saw him as a useful friend. He was particularly trusted by Charles Hillersdon, the Collector (senior British official) at Cawnpore. When the Indian Mutiny broke out, Hillersdon asked Nana Sahib for military assistance. The Nana’s troops moved into the town to guard the Treasury.

At this stage, it seems likely that Nana Sahib had not decided which side to ally himself with. Many of his advisers, especially Azimullah Khan, urged him to act decisively against the occupiers, and regain his rights and titles through military power, but he was unwilling to commit himself while the outcome of any war seemed in doubt. In any case, it seems likely that he had genuinely warm feelings for Hillersdon and some of the other British officials. On the other hand, he was proud of his Indian heritage and his position as Peshwa – a position the British were still refusing to acknowledge.

After considerable vacillation, he threw in his lot with the rebels. Some people believe that he was forced to do so. The fact was, though, that the troops of his already in the town made resistance futile and, in any light, his action had to be regarded as a betrayal.

The British evacuated town and took shelter in a hastily constructed entrenchment on the outskirts. Despite the impossibility of their position, they held out against Indian attack for almost three weeks, when they were offered safe passage in return for their surrender. Their commander, General Wheeler, considered that surrender was an honourable option, given the almost certain death of the women and children in the Entrenchment were the siege to continue.

The Indians agreed that the British should evacuate Cawnpore by water. The British therefore marched out of the camp to the nearby river, where a small fleet of boats was waiting for them. However, as the British started to board the boats, the Indians opened fire. Only four of the soldiers from the garrison escaped alive.

Once the British had surrendered, it seems likely that Nana Sahib was pressured to agree to massacre them in order to prove that he was firmly on the side of the native population and that he would not be able to turn against them if (as happened) the British returned to Cawnpore in force.

The initial attack on the British after their surrender left many of the women and children alive and in Nana Sahib’s hands. Again, he seemed uncertain what action to take. He did not kill his captives and, although their conditions were not good, he seems to have done his best to provide them with reasonable food and shelter. To the extent that they were ill-treated, this seems to have been largely due to the attitudes of some of the people who were dealing with them on a day-to-day basis, while Nana Sahib kept his distance. Eventually, though, the decision was made to massacre the women and children. At the time, the English straightforwardly blamed this on Nana Sahib, but there is no record of who actually ordered the massacre. Many people think the decision was taken by Azimullah Khan. Nana Sahib himself refused to witness the massacre.

After Cawnpore was once again firmly in British hands, Nana Sahib disappeared. He was said to be hiding out in Nepal. Margaret Oldfield, the wife of the British Residency doctor there, wrote that the Resident “has not the slightest doubt that these monsters are alive” in Nepal. The matter was a diplomatic problem as Britain was anxious to maintain friendly relations with Nepal and the Nepalese government was unwilling to hand over a Brahman to face certain death. The situation was resolved by concocting a story of the death of the Nana. Nobody believed it, but it suited both governments to accept the fiction and Nana Sahib was left in peace. Although he was widely believed to have died there by 1906, a report in the The Hindu (a major Indian newspaper) in 1953 claimed that he had moved back to India. There, they said, he lived out his life little more than a hundred miles from Cawnpore, finally dying in 1926 at the age of hundred and two.

Cawnpore

Cawnpore is the second book in my John Williamson trilogy, although it can be enjoyed without reading the first. (If you want to read all three books, this is probably a good time to mention that they are now available as a Kindle bundle.) After his adventures in Borneo (The White Rajah), Williamson takes a job with the East India Company at Cawnpore. After his time with James Brooke, the relationship between the rulers and ruled in India comes as a shock, but he finds a friend at the court of the Nana Sahib. When rebellion breaks out, he is caught between his loyalty to the European community and his friendship in the Indian court. As the tensions between the two communities move toward atrocity and counter-atrocity, can he be true to his friends and keep both them and himself alive?

Cawnpore is not a particularly easy book to read (lots of people have told me it has them in tears) but this story of a decent man caught up in the horror of colonial war is one I am particularly proud of. At the time, my son was serving with the British Army in Afghanistan. The issues that were so obvious in 1857 are still there today and I am grateful to have had the chance to write about them.

Cawnpore is available on Kindle and as a paperback. It can also be bought through Simon & Schuster and Amazon in North America. Note that the cover may be different in North America.