by TCW | Nov 2, 2018 | Napoleonic history

Last week’s blog looked at the way that the wounded at Waterloo were treated. We saw that many were left for several days on the battlefield and even once they had been taken off the field for treatment conditions were harsh and most died. It’s worth remembering that when we read about the numbers of deaths in battles of this era these are the numbers of people who died

on the day. Actual casualties including all those who died of their wounds later were invariably much, much higher.

Even so, those who did get treatment were the lucky ones. What happened to everybody else?

Scavenging the dead (and the not quite dead)

Even while the last of the fighting was going on, scavengers were out to take what they could from the dead. By nightfall there were many scavengers working their way through the field. The accounts of survivors who spent the night wounded in the open are quite terrifying. Col Ponsonby of the 12th Light Dragoons was injured late in the afternoon and robbed by a French soldier during the battle:

A tirailleur stopped to plunder me, threatening my life. I directed him to a small side-pocket, in which he found three dollars, all I had; but he continued to threaten, and said he might search me: this he did immediately, unloosing my stock, and tearing open my waistcoat, leaving me in a very uneasy posture.

The battle over, he is then searched by a Prussian after plunder.

The groans of the wounded all around me became every instant more audible: I thought the night would never end.

It was not a dark night, and Prussians were wandering about to plunder… Several stragglers looked at me, as they passed by, one after another, and at last one stopped to examine me. I told him, as well as I could, for I spoke German very imperfectly, that I was a British officer, and had been plundered already; he did not desist however, and pulled me about roughly.

Soldiers were not well paid and the opportunity to plunder was definitely one of the perks of the job. Being plundered by people who were supposed to be on your side must have been a bit of a blow though.

It’s easy to take a censorious view of the civilians who moved onto the battlefield stealing anything they could. Many bodies will have been stripped naked – boots, especially, being much prized. You have to remember, though, that people living in the area will have lost everything because of the war. Their crops will have been trampled, their homes may well have been destroyed and anything valuable is likely to have been looted. The Prussians, in particular, were prone to kill livestock on French farms simply because they hated the French so much. In the circumstances, the only restitution that people were going to be able to get was that they took for themselves by stealing from the corpses.

A particularly macabre theft was that of teeth. In the early part of the 19th century, rich people with plenty of money but very few teeth were prepared to pay well for a good set of dentures. These were usually made from ivory but they did not always look natural. The best dentures were made with an ivory base and then set with real human teeth at the front.

Demand for human incisors far outstripped supply, making the theft of teeth from corpses on the Waterloo battlefield a lucrative operation. The number of teeth salvaged from the bodies led to dentures made with them being known as “Waterloo teeth”. Waterloo teeth were seen as more desirable than teeth from other sources as people knew they came from fit young man who had died suddenly from causes unconnected with disease. Given that some dentures were made with teeth recovered from bodies in cemeteries, the attraction should be obvious.

Dealing with the bodies

When we think of clearing bodies off the battlefield, we naturally start by thinking of the human dead, but a priority at the time was the horses. The corpses of horses are a more immediate problem as up to half a tonne of horse will rapidly swell with putrefying gases and poses a major health risk as well as smelling utterly disgusting. Where possible, horses would have been buried.

When the bodies of senior officers were recovered they might have been removed for burial, but most soldiers would have been buried in mass graves or the bodies would have been piled into a heap and burned. An officer described his experience:

The bodies of the killed were all completely stripped in an incredibly short time, and many in the course of a few days became horrible objects; such as lay exposed to the sun turning nearly black, as well as being much swollen … Entirely to clear the ground of dead men and horses occupied period of ten or twelve days … The human bodies were for the most part thrown into large holes, fifteen or twenty feet square …

Soldiers who died alone, separated from their comrades, might not have been gathered up with the other dead and there is no doubt that many bodies were simply left to rot. This ossuary near the battlefield contains bones that have been discovered in the course of agricultural work over the years.

Fertiliser

Farmers may have lost their crops in 1815, but they were at least rewarded with bumper harvests in subsequent years. The bone meal and blood fertilised the fields wonderfully.

The advantages of bone meal were well-known and entrepreneurs ‘harvested’ the fields of Waterloo for the bones of the dead, which were ground up and sold as fertiliser. This was the view of The New Annual Register in 1822:

The oily substance, gradually evolving as the bone calcines, makes a more substantial manure than almost any other substance, particularly human bones. It is now ascertained beyond a doubt, by actual experiment upon an extensive scale, that a dead soldier is a most valuable article of commerce; and, for ought known to the contrary, the good farmers of Yorkshire are, in a great measure, indebted to the bones of their children for their daily bread.

How do we see these things today?

The reader who commented that I didn’t pay enough attention to the dead of Waterloo made a valid point. We look back at these battles and we see the red coats of the British infantry and the shining breastplates of the French currassiers and we tend to forget how terrible the whole business was.

The books about James Burke were written as adventure stories, so it’s natural that there is more about the glory of war (and there definitely was some glory, if not as much as we remember) rather than the horror. Even so, with every book I wrote I found myself dwelling more on the dead and injured. In Burke at Waterloo one of my two main characters is injured in the battle and Burke finds himself reflecting on whether it was all worthwhile.

‘You’re very quiet, sir.’

Burke hadn’t realised he’d been brooding, until he heard William speak.

‘The war’s finally over, William. It seems unreal, somehow.’

‘But we’re going home, sir, safe and sound.’ He winced as his horse stumbled and his shoulder was jolted. ‘Well, almost sound. We saw off Napoleon and saved the world from tyranny.’

‘I suppose we did, William.’ And maybe they had. He didn’t know where Napoleon was now, but he was no longer Emperor of France. The Prussians were in Paris and Napoleon was on the run. Austria, Russia, Prussia, and Britain would carve up Europe between them. France had had its day of glory and nothing would ever be quite the same again.

William looked worried as he turned to Burke. ‘It’s been worth it, sir, hasn’t it?’

‘Oh, yes, William.’ He made sure to sound confident. It wouldn’t help for William to share his doubts. ‘It’s all been worth it.’

A reflective hero doesn’t necessarily sell (prove me wrong and buy the book) but the more you learn about the reality of 19th century warfare, the more reflective you tend to become.

And a request …

Warfare now is generally less bloody than it was then – strange but true. Even so wars leave a lot of injured soldiers and the governments that sent them to fight and die are not always as generous as they might be when they return with shattered limbs and often enormous psychological trauma. Rightly or wrongly, British soldiers have been fighting in some very odd places in recent decades and that has left a lot of young people still needing help. At this time of year especially, we remember them.

Please give generously to the Poppy Appeal.

by TCW | Oct 30, 2018 | Book review

Unquiet Spirits by Bonnie MacBird is a detective story set in 1889. It features suitably evil villains, a Scottish castle, a beautiful woman of mystery and possibly a ghost. It’s a jolly good read and I’ll happily recommend it to anyone who thinks that a book matching that general description is the sort of thing that might appeal.

It also features a detective called Sherlock Holmes. Does that make it any better than it would be anyway? Arguably not, but MacBird is riding a wave of Holmesian re-writes. Perhaps it is worth asking what distinguishes all these books and why they remain so popular.

In the past few weeks I’ve read three: this one, The House of Silk by Anthony Horowitz and Sherlock Holmes: The Adventure of the Primal Man by Derrick Belanger. There are many, many more with, as it were, ‘spin-offs’ like Laurie R King’s Mary Russell series, featuring a young girl who becomes the older Holmes’s protégé. And, though it’s a TV series and not a book, we can’t ignore Benedict Cumberpatch’s brilliantly presented re-imagining of the great detective in Sherlock.

Some of these writers go to great pains to capture the ‘voice’ of John Watson. Anthony Horowitz, in his essay on writing The House of Silk (which now appears in the paperback) says how important it seemed to him to get that voice right and I certainly felt I was reading something very close to the original. MacBird, by contrast, doesn’t read remotely like John Watson and neither does Belanger, who happily has Watson put the word ‘trash’ into Holmes’s Victorian mouth. King gets round the problem by writing not as Watson but as Mary Russell, which works well but means that there is no possibility of mistaking the books for anything Doyle might have written.

The fact that most Holmesian homages don’t read at all like the originals does not detract from their popularity and, though purists may carp, it doesn’t really spoil Unquiet Spirits. So, if the narrator’s voice (or, with King’s books, the narrator) isn’t what matters, what does?

Is it the character of Sherlock Holmes himself? Possibly. But what do we mean by the ‘character’ of Holmes? In this post-Trainspotting era, both MacBird and Horowitz make a point of having a drug-free hero and Belanger goes so far as to have had Holmes take up meditation in Tibet to explain the absence of drugs in his story. Holmes was always physically fit, but MacBird has him leaping “gazelle-like” over the furniture in his flat, which seems unlike the more cerebral figure that Doyle’s Holmes usually cuts at home. When I close my eyes and think of MacBird’s Holmes, I must admit I see Benedict Cumberpatch.

Arguably, it is not the physical manifestation of Holmes that draws us to such stories. Isn’t the most important thing watching the deductive powers of the “human calculating machine” at work? Horowitz presumably thinks so: he provides several examples of the parlour tricks that Holmes loves to play on visitors.

“I can tell that you have just returned from Holburn Viaduct. That you left your house in a hurry, but even so missed the train. Perhaps the fact that you are currently without a servant girl is to blame.”

MacBird offers fewer of these coups de theatre and, when Holmes attempts them, he is often proved wrong. (Even Horowitz has him make the odd mistake: the 21st century is much more sceptical of genius than the 19th.) MacBird, I think, does herself no favours by cutting back on this element of the original books. They are fun, and part of the definition of the genre, but they are clearly not absolutely essential to Holmes’s character.

So what is the essence of Sherlock Holmes?

Oddly enough, I think the clearest contemporary comparison is with Batman. Batman was first introduced to the world in Detective Comics in 1939 and is often referred to as “the greatest detective”. More importantly, though, he is not a super-hero, but a man who has achieved greatness by rigorous training and commitment to his cause: fighting crime and destroying evil. He has thus reached almost super-human standards of excellence in his crime-fighting role. He has a tragic past and is now isolated from most regular social interaction, except with his side-kick, Robin, and his butler, Alfred, who attends to his practical daily needs. He has no meaningful relationships with women and his past is shrouded in tragedy.

Holmes, like Batman, appeals because he represents what humans can achieve by sheer application. He has become great, reaching standards of analytical reasoning that appear almost magical. This almost mystical persona is enhanced by the fact that he has no regular social relationships and we see him through the prism of his faithful side-kick, Watson. He doesn’t have to worry about his practical daily needs, because these are met by Mrs Hudson. He has no meaningful relationships with women and his past is shrouded in tragedy.

Both Batman and Holmes have attained almost mythic status in their respective literary worlds, because the figure they represent touches on a Platonic ideal of the ideal man (and both figures are men – female Bats and Holmes are occasionally imagined but never threaten the original). Human, yet separated from common humanity, born out of tragedy and doomed to an isolated existence, dedicated to serving the common good, Holmes, like Batman, is a mythic archetype.

MacBird’s Holmes measures up in many ways and she devotes a significant part of the story to probing his tragic past. On the one hand, this builds on the myth by confirming what we all suspected: Holmes’s past was, indeed tragic. On the other hand, by spelling out the details, some of the mythic element is lost. Holmes is no longer some sort of uber-mensch forged from tragedy, but a rather sad and solitary individual who has never recovered from the murder of his first love. Holmes’s back-story, although woven into the main narrative, isn’t necessary and, far from making Unquiet Spirits a seminal part of the Holmesian canon, it detracts from the traditional view of the great detective.

Horowitz seems more assured. As with Doyle, Holmes is front and centre of the story, his character always observed through the often adulational eyes of the trusty Watson. His Holmes is always more weighed down by his failure to protect everyone whose paths he crosses than it is buoyed up by his successes. He is a tragic figure rather than (as with MacBird’s Holmes) a figure shaped by a specific tragedy.

Belanger’s Holmes is hardly tragic at all. The hero of The Adventure of the Primal Man is just a very clever man who shares Holmes’s name and address but adds nothing to the canon. It’s a lightweight piece compared with House of Silk or Unquiet Spirits, but it represents the way that Holmes keeps popping up in contemporary literature when an author needs a great detective and a period setting. They don’t develop the character of Sherlock Holmes, but may be no less entertaining for that. And at least Belanger hasn’t given Holmes a girlfriend.

Holmes, then, turns up in contemporary literature (not to mention films and TV) in a variety of guises ranging from a careful recreation of Doyle’s hero to a generic Victorian, or early Edwardian, detective, to a reimagining for the 21st century (possibly complete with bat costume). What is the appeal? It’s not Doyle’s literary genius. The stories are well-written and workmanlike, but Doyle himself despised them, hence the Reichenbach Falls where he tried to put an end to the character once and for all. (Doyle thought his literary heritage would be a series of historical novels set in the 14th century. They were quite popular, but have not stood the test of time.)

In the end, Holmes represents certainty: the triumph of good over evil by the application of rational thought. He is a god-like figure for a scientific age. Born in a time when people believed, apparently with good reason, that the problems of the world could be solved by scientific progress, he has become, paradoxically, more popular when the most casual glance at a newspaper suggests that the world’s problems are insoluble. We need to believe that out there somewhere there may be somebody who can apply his mind to any problem and come up with an answer that is not only correct, but has been obtained by a process of rational reasoning. Holmes always gets the answer by logic, rather than luck, and Watson – representing us mere mortals – always spells out the details of Holmes’ reasoning so that we can see that no magic has been involved.

Ironically, Doyle himself believed in spirits and was taken in by the most amateur of faked photographs of fairies. Those who know his life story may feel sympathy (his belief in spiritualism was driven by the loss of his son in World War I) or we may mock. But in either case, we are likely to cling all the harder to the philosophy of Rationalism and seek out another story based in the extraordinary powers of the mind of the Great Detective.

This article first appeared on the website of the Historical Novel Society.

by TCW | Oct 26, 2018 | Napoleonic history

While I was writing here about Waterloo, I had a suggestion that I wasn’t paying enough attention to the human cost of the battle. I promised I would come to this and we’ve not talked about Waterloo for a while, so this week might be a good time to come back to the battle and. more particularly, its aftermath.

Waterloo was far from the bloodiest battle of the Napoleonic wars (that dubious distinction belongs to Borodino). However, the number of dead in such a small field was horrific. An idea of what it was like can be gathered from this account by an anonymous private soldier:

In the first place, the ground, whithersoever we went, was strewed with the wreck of the battle. Arms of every kind, cuirasses, muskets, cannon, tumbrils, and drums, which seemed innumerable, cumbered the very face of the earth. Intermingled with these were the carcasses of the slain, not lying about in groups of four or six, but so wedged together that we found it impossible in many instances to avoid trampling them, where they lay, under our horses’ hoofs; then, again, the knapsacks, either cast loose or still adhering to their owners, were countless. I confess that we opened many of these, hoping to find in them money or other articles of value, but not one which I at least examined contained more than the coarse shirts and shoes that had belonged to their dead owners, with here and there a little package of tobacco and a bag of salt; and, which was worst of all, when we dismounted to institute this search, our spurs forever caught in the garments of the slain, and more than once we tripped up and fell over them. It was indeed a ghastly spectacle, which the feeble light of a young moon rendered, if possible, more hideous than it would have been if looked upon under the full glory of a meridian sun; for there is something frightful in the association of darkness with the dwelling of the dead; and here the dead lay so thick and so crowded together, that by and by it seemed to me as if we alone had survived to make mention of their destiny.[1]

Print of William Frye’s painting of Waterloo after the battle

Print of William Frye’s painting of Waterloo after the battle

The French had specialised sprung ambulances to transport their wounded, but in the chaos of the French defeat their wounded were abandoned on the field. As darkness began to fall, the victorious allies began to sort the living from the dead, carrying those who could not walk in whatever carts they could find.

We found on every side poor fellows dying in every variety of wretchedness, and had repeatedly to join the strictest silence that we might hear their scarcely audible groans … Before morning we collected several wagon-loads of brave fellows, friends and foes. [2]

Whilst the Allies did attempt to remove the casualties and give them medical care, the sheer scale of the exercise meant that people lay in the open for days – by which time, of course, most of them were already dead. Only after the Allied troops had been cared for did the British turn to the French. An anonymous Staff officer who was there wrote:

I have reason to believe it was not till the fourth day after the battle that the last of the French were taken up; and it is painful to think of the suffering they endured from pain, cold, and even hunger, during so many weary days and nights, – numbers of them, doubtless perished who would have survived had they been taken care of. Neither does it appear that any food was regularly supplied to them … [3]

The British had set up a field hospital at Mont St Jean in a big farmhouse that still stands today. This is an account of the site by a sergeant of the Scots Greys:

We having arrived at the farmhouse, Mont St Jean, which is situated on the road in short distance in front of the village of the same name, entered the yard, where a most shocking spectacle presented itself. This house and yard, during the time of the battle, had been occupied by some of the British and Belgic surgeons and in it many amputations had been performed. A large dunghill in the middle of the square, was covered with dead bodies and heaps of legs and arms were scattered around! A comrades who stood near me on entering unconsciously muttered “Oh God. What a sight.” To which I made no answer, but felt as he did, for a great number lay by the sides of the house and basked in the beams of the sun who had only life’s last spark remaining and gasped for relief. [4]

The farmyard at Mount Saint Jean as it is today

The farmyard at Mount Saint Jean as it is today

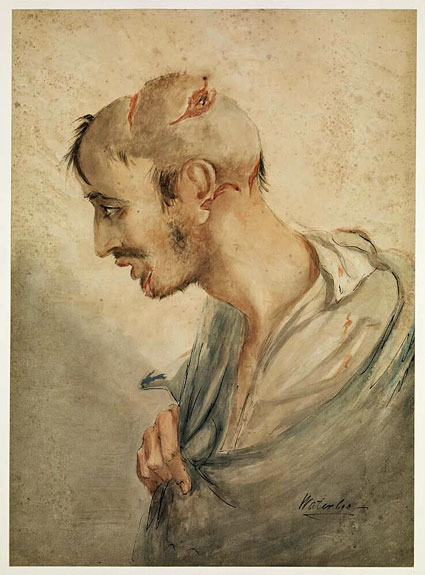

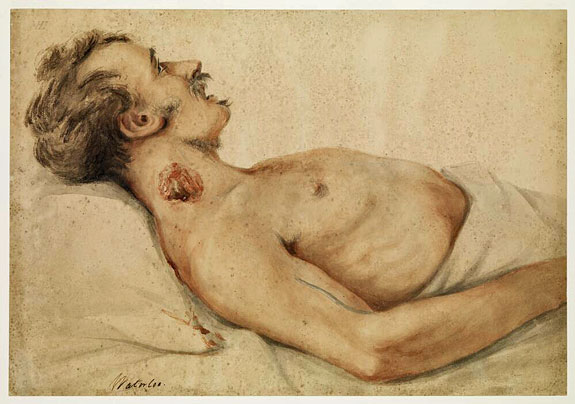

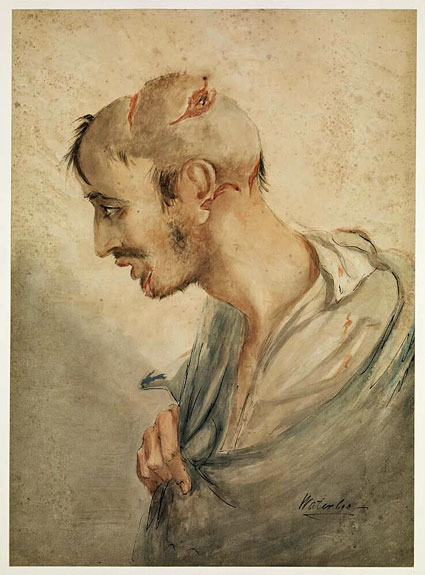

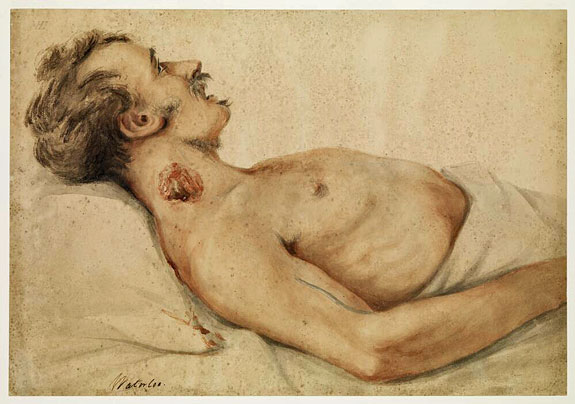

Here the surgeons had to deal with a range of injuries. The Scottish surgeon, Charles Bell, who was operating on French soldiers in the Gendarmerie Hospital, made detailed watercolour paintings of the sort of things treated at Waterloo.

Sabre wound to head. (Wellcome Library) Grapeshot wound to the neck (Wellcome Library)

Most wounds were caused by gunshot and the main concern of the surgeons was to remove the ball and ensure that the wound was left clean. Usually the ball would have carried fragments of clothing into the wound and these had to be carefully removed one by one with forceps. Remember that this would have been done while the patient was fully conscious.

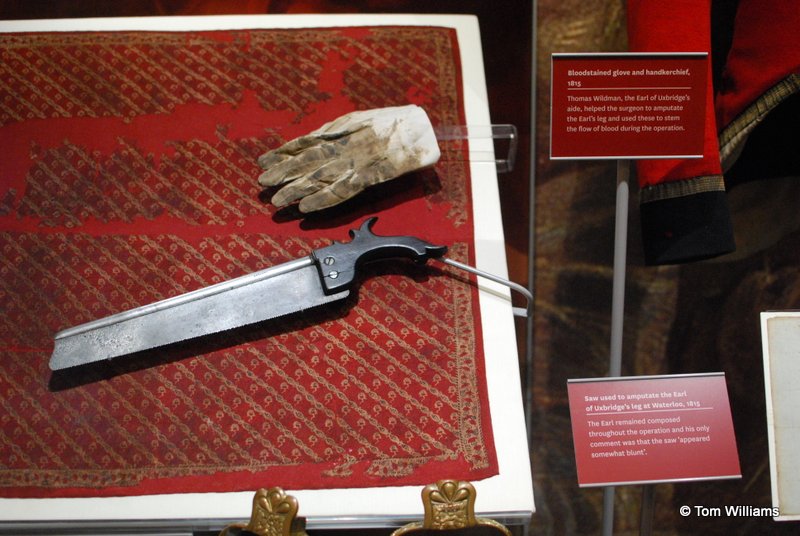

A major cause of death was infection. Gangrene was a particular problem. Without antibiotics the only way to treat wounds that were liable to turn gangrenous was by amputation. Arms and legs were cut off with gay abandon. There was a pile of detached limbs in the courtyard shown in the photograph above.

I observed with some warmth of national feeling, several highlanders’ legs, still wearing the emblem of their country; Auld Scotia’s tartan hoe! As also the legs of dragoons in boots and spurs and many others which still wore a part of the garment in which they had proudly paced the causeways of their native land. [5]

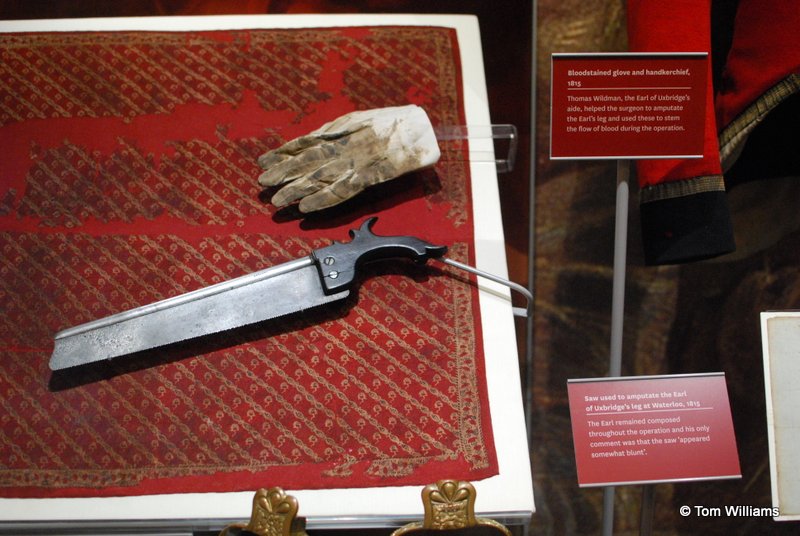

The secret of a successful amputation was that it should be done very fast. A sharp bone saw was crucial to a surgeon’s success rate. The photograph below shows the saw that was used to remove the leg of the Earl of Uxbridge, who had been hit by a cannon-ball while sitting on his horse alongside Wellington.

Bone saw displayed at National Army Museum

Bone saw displayed at National Army Museum

Surgeons had to work quickly so that their patients did not die of shock as they went through the amputations unanaesthetised. But there was another reason for speed as well. There were only 270 surgeons available to treat the wounded, and with tens of thousands of men requiring attention they had no time to spend on any but the most basic of procedures.

As the wounded were moved from the battlefield, so Brussels filled with makeshift hospitals. Soldiers who were less badly injured were cared for in the parks, because all the buildings were full, with contemporary accounts claiming that every private house had three or four wounded soldiers in it. [6] Modern authors estimate that around 62,000 Allied and French wounded flooded into Brussels, Antwerp, and other towns and cities of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. [7] The scale of the horror was such that a British tourist (himself an ex-Army man) wrote ten days after the battle:

You may form a guess of the slaughter and of the misery that the wounded must have suffered and of the many that must have perished from hunger and thirst, when I tell you that all the carriages from Bruxelles, even elegant private equipages, landaulets, barouches and berlines, have been put in requisition to remove the wounded men from the field of battle to the hospitals, and that they are yet far from being all brought in. [8]

References

- Quoted by Gleig in his Story of the battle of Waterloo p253

- Augustus Fraser: Letters of Colonel Sir Augustus Simon Frazer, K.C.B. commanding the Royal horse artillery in the army under Wellington, Written during the peninsular and Waterloo campaigns

- Recollections of Waterloo by a Staff Officer United Service Magazine 1847 PartIII p355

- Sgt William Clark, whose writings have recently been published as A Scots Grey at Waterloo edited by Gareth Glover

- Ibid

- After Waterloo – Reminiscences of European Travel 1815-1819 by W E Frye

- See, for example, Michael Crumplin and Gareth Glover (2018) Waterloo – after the glory

- Frye ibid

To be continued …

There is more about the aftermath of the battle in next week’s blog.

by TCW | Oct 16, 2018 | Book review

I read this book a couple of years ago and loved it, but the author was remarking on Facebook the other day that it has sunk without trace. She’s upset, because it was a personal favourite of hers and I agree with her that it deserves better. So I’m re-posting my review in the hope that some of you might decide to read it.

After exploring the middle of the 19th century with last week’s review of Fingersmith, this week may seem hardly historical at all. S.A. Laybourn’s A Kestrel Rising is set during World War II. There’s no doubt that stories set in the 1940s qualify as ‘historical’ but many people see ‘war stories’ as a separate genre. This, though, is no war story: it’s a romance told from the point of view of a young woman (Ilona) who has joined the WAAF to do her bit for the war effort by driving. She starts by driving pilots to their aircraft and she is soon adopted by the absurdly young men that she takes out to wait for what might be their last flight and who she greets as they return, frightened but putting a brave face on their adventures. Romance almost inevitably ensues, but then this idyll (he is handsome and kind; she is a virgin, desperately giving herself to the love of her life) ends with the death of the pilot. Around a fifth of ‘the Few’ died in the Battle of Britain and the book is very good at capturing the way that everyone in the RAF and WAAF had to live with the reality of friends and comrades dying or being horribly injured on a regular basis.

Ilona is emotionally destroyed by the loss of her lover and transfers to a job driving trucks between RAF bases, so she has less contact with the pilots. The war, though, touches every aspect of her life. Her family is terribly important to her but she hardly ever has the chance to visit them. So when it turns out that a distant relative has come over from America to sign up with the RAF, she feels obliged to spend time with him. In one of the book’s rare descents into cliché, she at first hates him before slowly growing close to him. But he is flying escort in the bombing raids on Europe – a role with a horrifically high attrition rate. Ilona is terrified to admit her feelings because she feels that she cannot face the loss of a second lover.

I would say that this is very definitely a ‘historical novel’. The romance is defined by the reality of war and the social attitudes of its time. It’s probably more driven by historical reality than most ‘historical romances’ where, one suspects, the details of the dresses are the only point at which real history touches the story. Here everything from the ring that her lover gives her to wear on their ‘dirty weekend’ to the impossibility of sleeping together when he visits Ilona’s house (though her parents are under no illusions as to their relationship), all catch the combination of social repression and sexual liberation that seems to have typified the war years.

Laybourn also writes with real understanding about the emotional agony of losing a lover to death. It’s probably only fair to say that I have been a ‘virtual friend’ of this author for a while (though I have never met her) and I know that these passages reflect her own experience. They are written from the heart and rise far above the mawkishness that can characterise some romantic writing.

While this is a romance, rather than a war story, Laybourn has a scarily precise grip on the different sorts of fighter planes used in the war and the various ways in which you could die in all of them. When the pilots describe their experiences, they ring absolutely true. There’s also interesting stuff about the position of US airmen as the US finally joins the war.There are, of course, places where reality gives way to the necessities of keeping the plot moving. Realistically, there are an awful lot of railway journeys (the only way to travel any distance when off-duty) but, unrealistically, our hero and heroine always get seats, so they can move the story along with meaningful conversations. While it is remarked on as lucky, accounts I have read of wartime travel suggest it was little short of miraculous. And once the war is over, everybody is demobilised practically overnight so that Laybourn can hurry us to the inevitable happy ending. (I was holding out for a dark twist where they survive the war only to die in a freak motorcycle accident on the first day of peace, but I’m not your average romance reader and it was never going to happen.) There are an awful lot of goodbyes at stations (I felt sometimes that I was on a constant rerun of ‘Brief Encounter’) but that’s probably realistic and if the desperately stiff upper lips and ‘I do love you, darling’s seem ridiculous in 2016, I doubt they did back then. The one occasion where they take a return rail journey and end up back at a different London terminus is less convincing, but perhaps the usual route was blocked by bombing or something. It’s the only obvious ‘gotcha’ so I’ll give it the benefit of the doubt.

Beautifully written, with credible characters you come to care about, this book works as a romance and as a novel of the Second World War. I recommend it.

by TCW | Oct 12, 2018 | Uncategorized

It’s Friday when, as you’ve probably noticed, I generally post something on my blog. I didn’t last week because I was away and I haven’t prepared anything for this week. So what’s been going on?

Well, I hope you have seen from all the times I mention it that I’ve been away in Malvern at the Festival of Military History. I must admit that before I went there I hid in Wales for a few days, where we have no phone or Internet. If that seems impossibly primitive, I should mention that our water comes from a well and we’re heated with oil that is delivered in a big tanker every now and then.

It was lovely to catch up on reading. Here at home, with the constant distractions of Internet and e-mail (and occasional house work) it’s not that often that I sit down for any period of time and lose myself in a good book. I was lucky to have taken Candy Korman’s Bram Stoker’s Summer Sublet, a gloriously silly spin on vampire stories, set in today’s New York. Wilhelmina (obviously cursed from birth with a name like that) is recovering from the shock of finding her fiancé in flagrante with another woman and has decamped to a stranger’s house to pet-sit her dog and strangely loquacious parrot, while her now ex-fiancé enjoys the honeymoon they would have spent together in Italy. She is in an understandably emotional state – the sort of emotional state where you might easily decide that your next door neighbour is a vampire. Having another neighbour whose name is Dr Van Helsing probably doesn’t help keep her imagination in check. Or is it all her imagination? (I’m not telling – you’ll have to read it for yourself.)

Candy Korman has a lovely prose style and writes with a strong sense of place. I felt I was in New York – quite an achievement isolated in the middle of Wales. Ms Korman has written several books based around old-school monsters and I’ll definitely be reading another.

Break in the country or not, there was no escape from Waterloo, whether David Crane’s Went the Day Well?, looking at the battle and its wider social context hour by hour or the 19th-century accounts like Chesney’s Waterloo Lectures or Bain’s less well-known Detailed Account of the Battles of Quatre Bras, Ligny and Waterloo. I generally prefer the 19th-century accounts. Modern historians will tell you that recent writings on the period give a more accurate idea of what happened, but I’m unconvinced. There’s no percentage in simply parroting the accounts of people who were there, so modern analysis often consists of interminable arguments about whether Napoleon or Ney was actually commanding the army in the field which, given that both of them have been dead for around 200 years, seems an exercise in fatuity. That said, there are some glorious new findings, like the forensics analysis of the position of every piece of munitions that modern techniques can find in the vicinity of Hougoumont, which genuinely does give us a better idea of how the battle there happened. That kind of thing is the exception though.

This brings these meanderings more or less logically to the Festival of Military History, which was unexpectedly fabulous. There were the inevitable arguments about Waterloo and a lecture on Napoleon, though even there people had interesting things to say. Perhaps the most fascinating thing for me, given what I just said about history’s best days being in the past, were presentations by Serena Jones and Ismini Pells. Both demonstrated that we can learn a lot more about the Civil War by reading documents that have been languishing in archives for the past 350 years and which provide really valuable insights into the period.

I had my moment of glory on a panel about writing historical fiction, which I shared with some much better-known writers like Iain Gale. Everybody was incredibly generous and I hardly felt out of my depth at all. All in all, it was a thoroughly good weekend and, if it is repeated, as planned, next year, I do recommend that you all go to it.

It gave us an excuse to walk the Malvern Hills, too, which is a new part of England to me and well worth a visit.

Anyway, now I’m back and all blogged out. Does anyone have anything they would like me to write about next week?

Print of William Frye’s painting of Waterloo after the battle

Print of William Frye’s painting of Waterloo after the battle The farmyard at Mount Saint Jean as it is today

The farmyard at Mount Saint Jean as it is today

Bone saw displayed at National Army Museum

Bone saw displayed at National Army Museum