by TCW | Feb 12, 2019 | Book review

My visit to Strawberry Hill made me re-read The Castle of Otranto, Walpole’s novel which is supposed to have started a fashion for Gothic novels that has never really gone away.

Published in 1764, it’s a curiosity piece rather than a book you would read for its literary merit. Seriously, it doesn’t have any literary merit but it does have a giant ghost that can smash down castle walls with his fists; an evil usurper; not one, but two, beautiful princesses; a peasant boy who turns out to be a prince (identifiable by a birthmark, obviously) … Honestly, if Walpole missed out a single Gothic trope, it wasn’t for lack of trying. Despite the packed plot line, it’s quite a short book and if you want to read the great-grandfather of all Gothic novels it’s an hour or two not entirely wasted.

The Castle of Otranto from an illustration in the original book. Rather larger than Strawberry Hill

The Castle of Otranto from an illustration in the original book. Rather larger than Strawberry Hill

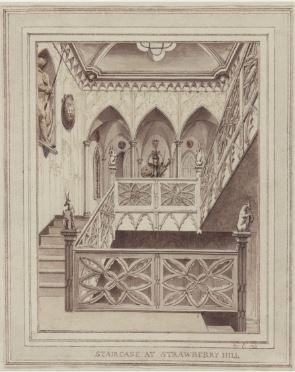

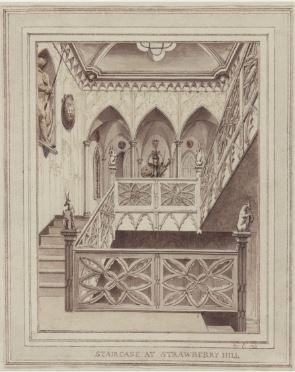

For me, part of the fun came from the fact that the architecture of Strawberry Hill House is supposed to have inspired the book. (Walpole called Strawberry Hill “my own little Otranto”.) Sadly, Strawberry Hill lacks an underground passage to a nearby church although Walpole’s neighbour, Pope, did build an underground passage from his house to the famous grotto and this might have inspired Walpole’s imagination. Much of the rest of the story’s setting also has only tenuous links with Strawberry Hill House, but there is indeed a staircase with some assorted pieces of armour. Originally there was a lot more than we see today. Walpole claimed, rather improbably, that the armour had all been taken by one of his ancestors in the Holy Wars (though the descriptions of Indian weaponry make this unlikely). In any case, the armour inspired the story of the giant armoured knight who brings the Castle of Otranto to its doom and which we first meet in one of the rooms leading off the “armoury” gallery. Two servants bring the news to Manfred, the usurper Prince of Otranto.

“My Lord,” said Jaquez, “when Diego and I came into the gallery … We found nobody. … When we came to the door of the great chamber … We found it shut.” “And could not you open it?” said Manfred. “Oh yes, my lord; would to heaven we had not,” replied he. … “Trifle not,” said Manfred, shuddering, “but tell me what you saw in the great chamber, on opening the door.”… “It is a giant, I believe; he is all clad in armour, for I saw his foot and part of his leg …”

Sadly, the great chamber is a library – albeit quite a big and beautiful one – and the “gallery” is really no more than a landing, but Walpole deliberately arranged for the light to be gloomy just there so with a bit of effort of the imagination you can transport yourself from Twickenham to Italy and the cursed Castle of Otranto.

Further Reading

If you are interested in some of the themes underlying the book and the building, you might like to look at Reeve’s 2013 article on “Gothic Architecture, Sexuality, and License at Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill.” (The Art Bulletin, 95(3), 411-439.) There’s a lot of dubious pretension in the paper, which is not an easy read, but it does argue that both the book and the building were ways in which Walpole explored his sexuality. There is, indeed, quite a strong Freudian subtext in the book, which I have not explored in this blog post. The pictures of the Castle of Otranto and the staircase at Strawberry Hill are both taken from Reeve’s paper (worth a look for the illustrations alone). Reeve credits them as public domain artwork, photographed by the Lewis Walpole Library at Yale University.

by TCW | Feb 8, 2019 | Uncategorized

In 1747, Horace Walpole, the son of Britain’s first Prime Minister, bought a small house near the Thames in Twickenham which he was to transform into a Gothic castle.

Where the Gothic Castle now stands was originally a small tenement, built in 1698 and let as a lodging house: Cibber once took it, and wrote one of his plays here.

From Walpole’s own ‘Description of the Villa of Horace Walpole’ (1774)

The original house (much embellished with what we might now think of as an excess of post-modern enthusiasm) can be made out on the right of the photo below, with the smaller windows.

Walpole was attracted to the location because of the many grand houses along the river nearby. Neighbours included Henrietta Howard at Marble Hill House, which I’ve written about here before. Alexander Pope, who had died in 1744 had lived less than half a mile away and built his famous grotto in Twickenham.

Walpole was an enthusiast for the revival of interest in Gothicism. His book, The Castle of Otranto, published in 1764, is regarded as Britain’s first Gothic novel. He decided to take the undistinguished house and convert it into a Gothic palace. The result was Strawberry Hill House.

Strawberry Hill House. Photo reproduced under Wiki Commons licence

Walpole’s grand design stretched as far as the round tower. The small section that stretches beyond the tower (with an outdoor staircase leading to the first floor) was built later as a ballroom and other rooms were added to the original house. The whole thing, as built by Walpole, combined a Gothic grandeur with a very domestic scale. If you count the windows, you’ll see that it’s not that large. Indeed, it was intended only as a summer villa and was closed up in the winter. Visiting it last weekend on a cold February Saturday, I can confirm that no one would want to stay there in the winter.

In 1923, the building was bought by the Catholic Church, who used it as a teacher training college. Walpole’s original building was used for teaching and as a residence for the monks and, indeed, the grounds and many of the later additions to Walpole’s house are still part of what is now St Mary’s University.

In 2007, the original parts of the House were leased to a Trust to restore it and open it to the public. They have done a splendid job and visitors can now enjoy the wonderful Gothic fake in all its 18th century glory. You enter through a dark, mysterious entrance hall through rooms lit by skylights and stained-glass windows, until you arrived in the great State Rooms, full of light and gilding, the journey from darkness to light being, in Walpole’s view, part of the Gothic experience. The photo below shows the Gallery. Fifty-six feet long, thirteen wide and seventeen high, this is the most splendid room in the house. The gold leaf used on the ceiling was the most expensive single element of the restoration. As with all the other detail in the house, the Gothic elements have been shamelessly stolen from elsewhere. In this case, the ceiling is a copy of that in one of the side aisles of the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey. Although visually convincing, it is not really a fan vault, since it does not support the roof, being made of papier mache.

The Gallery

The use of other materials to give the effect of stone is common throughout the building. Many of the apparently stone walls and ceilings are brick and wood panelling, carefully painted to give the appearance of stone. Similarly, some of the fireplaces, which may look like stone or marble, are painted wood. A good example is the chimney piece in the Library. Again, the details are copied from genuinely Gothic elements: in this case the chimney piece is based on the tomb of John of Eltham Earl of Cornwall in Westminster Abbey while the stone work is copied from the tomb of Thomas Duke of Clarence at Canterbury.

The Library

The building itself, though, was only part of Walpole’s grand design. It was to house a collection of paintings, ceramics, antiques and curiosities on a Gothic theme. Walpole inherited money from his father, Britain’s longest serving prime minister, and was also granted some governments sinecures which made him seriously rich. He spent much of his money on his astonishing collection, with paintings by Sir Joshua Reynolds, Rubens, van Dyck, and Holbein. He had over 1,500 pieces of ceramics, Fine furniture, and curiosities such as a lock of Mary Tudor’s hair and Cardinal Wolsey’s hat.

Walpole was proud of his collection but he accepted that it would not long outlast him and he very carefully documented it so that there would be a record of what he had achieved. He wrote:

It would be a strange fascination … to expect that a paper fabric and an assemblage of curious trifles, made by an insignificant man, should at last or be treated with more penetration and respect than the trophies of a palace … [T]he following account of pictures and rarities is given with a view to their future dispersion.

The collection passed down eventually to George Waldegrave, the 7th Earl Waldegrave, who appears to have led a somewhat dissolute life (he served prison time for assaulting a local policeman) and eventually had to sell the collection, probably to pay off gambling debts. Walpole’s famous collection was dispersed in a 24 day sale in 1842.

Walpole’s detailed catalogue meant that in 2018 it became possible to locate many of the items from the collection which were loaned to Strawberry Hill to enable them to mount an exhibition giving some idea of what the house would have looked like with the artefacts it was designed to house.

Sadly, it was a condition of some of the loans that they can’t be photographed, so I have no photos from my visit. (The pictures of the house are from an earlier trip.) If you want to see them, I recommend you look at the web-site set up by Yale University (who own much of Walpole’s collection): http://images.library.yale.edu/strawberryhill/

Seeing Walpole’s beautiful building with even a fraction of the treasures it was built to house is a wonderful experience. The exhibition only runs to 24 February and I do recommend that if you have the chance you go and visit it.

Practical stuff for visitors

Nearest station: Strawberry Hill (from Waterloo). The house is a five to ten minute walk from the station: follow the sign at the end of each platform.

Entrance is by timed ticket and it does get busy (though never uncomfortably crowded). Details and tickets are online at https://www.strawberryhillhouse.org.uk/losttreasures/

by TCW | Feb 5, 2019 | Book review

‘The Wolf and the Watchman‘ publishes on Thursday and the Sunday Times carried a long review this weekend. Thanks to NetGalley, I was sent an advance copy of the book, so I’m able to review it today.

It’s 1793. Sweden is a major military power in the region and has recently been at war with Denmark, Norway and Russia. Internally the king has been assassinated. Revolution is breaking out in France and there are fears it will spread throughout Europe. Life, it is fair to say, is not a bundle of laughs.

When the limbless corpse of a young man is pulled from the sewerage that pools in the rivers that Stockholm is built on, Mickel Cardell, a drunken watchman, ends up working with the lawyer, Cecil Winge, to find out who is responsible for the crime.

You could reasonably say that this is a detective story. In Winge it has a detective and, eventually, the crime is solved, but this is a detective story like no other I have ever read. Winge’s investigations take the reader into the underbelly of late 18th-century Stockholm with a degree of detail that means I would not encourage you to read the book too soon after a full meal. Sexual sadism, common or garden sadism, brutality, starvation, fraud, robbery, rape – these are the everyday facts of life and Niklas Natt och Dag spares us no details. Cardell and Winge are both, in their own ways, trying to be good people, but they admit that their city is, in truth, beyond redemption.

The story should be profoundly depressing, but somehow it is not. Cardell and Winge are both fascinating characters. Cardell has lost an arm fighting the Russians and is constantly haunted by the guilt of surviving a battle that saw his closest friend die. Winge is dying of consumption. Both seek some sort of redemption by solving this crime, the more so as they come closer to understanding the prolonged horror of the victim’s death.

Winge is a rationalist, convinced that some sort of order can be imposed on the world by logic. Cardell is more emotional. Neither alone has any hope of success, but together they make progress.

The characters they meet on the way are as crucial to the success of the novel as is the plot. There is the young would-be surgeon, who loses his money in a gambling fraud and is trapped into becoming complicit in the long slow death of the victim. There is the young woman who turns away a man’s advances and, in revenge, is denounced as a prostitute. It is the meeting of these two which provides one of the few genuine opportunities for redemption in the book. (It’s a measure of the general misery that the act of redemption involves suicide, but then we can’t have everything.) And there is the evil villain – a man so comprehensively repellent that only a detailed back story including his even more repulsive father makes him at all credible. Sadly the quality of the writing means that he is all too credible indeed.

Yet, against a background of almost unremitting bleakness, The Wolf and the Watchman allows moments of light, the more intense for the darkness that they illuminate. Cardell finds the opportunity to save one innocent life, Winge discovers that sometimes rationality has to give way to the imperative to do the right thing. One of the guilty is punished, which is, as I’m sure Winge would argue, is better than nothing. One, at least, of the innocent is saved (as are several of the not-quite-as-guilty – but it’s the 18th century, what did you expect?)

Stockholm remains a mix of great beauty and incredible squalor. The corruption that taints every layer of society is about to be challenged as Europe trembles on the brink of Revolution and War (though an interlude in Paris makes us realise that one set of vices will simply be driven out by another). Winge, waking covered in blood will be dead in days, if not hours. Cardell, by contrast, may have found redemption in this life.

This is not a cheerful book, but it is a very, very good one. I recommend it wholeheartedly.

by TCW | Feb 1, 2019 | Uncategorized

A fairly random blog post this week dating back to last September when I went to see Hurlingham House, famous as the home of international polo. (I know: it makes no sense to me either. But it is.) This was just the last of the grand houses that we visited last year before we decided to hide indoors and wait for Spring.

Hurlingham House sits on the Thames at Fulham. Actually, when the Thames floods, it sits *in* the Thames: several inches of water covered the ground floor when the Thames burst its banks in 1928.

The house was originally built in 1760 as a “cottage” for Dr William Cadogan, a doctor whose book, ‘An Essay upon Nursing and the Management of Children from their Birth to Three Years of Age’ made him the Dr Spock of his day. The doctor died in 1797 and the relatively humble house was refronted in the early 1800s, producing the rather grand river frontage we see today.

The central room between the two wings is oval in shape, which put me in mind of another building of a similar period. The White House was rebuilt in 1815-17 after the original was burnt down by the British.

The President’s House by George Munger.

Today’s Oval Office was only built in 1909 but there was an oval room at the centre of the original White House and this was retained when the White House was rebuilt after the fire. Wikipedia assures me that:

An oval interior space was a

Baroque concept that was adapted by

Neoclassicism. Oval rooms became popular in eighteenth century neoclassical architecture.

Hurlingham House is the only UK example I’ve noticed myself and the parallels with the original design of the White House are interesting. (The South Portico, which emphasises the oval, was not added until 1824.)

Back in Fulham, the estate was leased to a private club in 1869 and it has been the Hurlingham Club ever since. The Hurlingham Club started life as a pigeon shooting club and went on to become the home of polo. (The Hurlingham Polo Association is still the governing body for polo in the UK and many other countries throughout the world.) Nowadays the club offers many sports, from swimming to croquet. The house, though important, is not necessarily the club’s main attraction for many members. Over the years it has been modified, enlarging the space available for dining rooms and bars and removing the bedrooms, which have largely been replaced with offices.

The most significant changes were made in 1906 the north front and much of the interior was remodelled by Sir Edwin Lutyens.

Edwin Lutyens’ remodelled north front

by TCW | Jan 29, 2019 | Book review

I seem to be getting more and more in to the 17th century. I really never meant to. It started with my visit to Edgehill and dinner with the Sealed Knot and then I found myself caught up in Jemahl Evans’ historical novel (as much history as novel in places), The Last Roundhead. After that I was plunged into the world of Mr Pepys, as summoned up in fantastic (and again historically grounded) detail by Deborah Swift in Pleasing Mr Pepys. I enjoyed that so much that I moved on to Deborah Swift’s story that took me to a dirtier, more dangerous and far less pleasant side of the same world in The Gilded Lily.

Perhaps Sapere Books have noticed, or perhaps I was just lucky, but they recently sent me a copy of M J Logue’s An Abiding Fire, set in Restoration London with a tiny walk-on part for Mr Pepys.

“Madam, if you consider that smellsock to be a decent anything you have yet to have any acquaintance with his wife. She has a number of stories to tell and none of them reflect very well on her husband.”

Poor Pepys, still routinely abused after more than three centuries, but that’s what you get for recording all your indiscretions in your diary.

Can you already tell that I liked this book? For I surely did. It’s a lovely, rollicking read with beautifully believable characters – many of them all more believable because they really existed and, as far as I can tell, Ms Logue has done her homework on the detail of their lives.

The story centres around the adventures of Major Russell, once one of Cromwell’s Roundheads, but now firmly on the side of the King. He has just married his childhood sweetheart, young, beautiful, and generally seen as somewhat out of his league. I’ve reviewed romances before and acquired a reputation as a nasty, cynical man who just can’t lose himself in a tale of true love. But here, I’m happy to turn into the fluffiest of romance-loving bunnies. We see the development of the relationship in the first months of a new marriage with chapters from the point of view of Major Russell alternating with scenes viewed through the eyes of Thomazine. There are rows, misunderstandings, reconciliations and all the passionate intensity of a relationship that is still setting out its own ground rules. It’s an absolute joy and would justify time spent reading all on its own.

This book, though, is not primarily a romance. (I suspect this is part of the reason that the romance element is so incredibly well done.) Britain is on the verge of war with the Dutch and Major Russell is one of King Charles’s spies. Soon he is caught up in a plot that seems designed to blame him for a sudden wave of murders and arson in London town. Who is behind these attacks, which seem designed to benefit the Dutch? Who is starting the rumours that claim Russell is a murderer and a traitor? (This is definitely the weakest point of the book. [POSSIBLE SPOILER if you really aren’t very good at whodunnits.] Who knows Russell well enough to be able to make such credible lies and who has a reputation throughout London, apparently, as a notorious gossip? Answer these two, not particularly difficult, questions and you will have identified the villain before poor Major Russell and wife have even got started.)

Never mind that Russell and his wife clearly aren’t the greatest detectives of their age. They’re brave and they’re fun and they love each other and they have beautiful friends with beautiful clothes who may be reprehensible but are wittily reprehensible, which seems to have been what mostly mattered in Charles II’s court.

There’s a climax with Thomazine suitably imperilled and Russell appropriately brave and the whole thing is set in the ropery at Chatham, which was a bonus as far as I’m concerned because I’ve been to the ropery at Chatham and it’s a remarkable building and I found the scene Logue describes came vividly to life for me.

The ropery at Chatham

The ropery at Chatham

Of the book I’ve read recently in this period, Ms Logue’s is probably the least worthy and the most fun. But it is a solid piece of historical writing (the Historical Note is practically a text book in itself) and I’m all in favour of fun. If you read it quickly you’ll have finished almost in time for the sequel, A Deceitful Subtlety, published just about now.

The Castle of Otranto from an illustration in the original book. Rather larger than Strawberry Hill

The Castle of Otranto from an illustration in the original book. Rather larger than Strawberry Hill

The ropery at Chatham

The ropery at Chatham