Please note that I have switched to posting on Substack and posts here are gradually fading away. If you like my posts, can you please switch to subscribing to me on Substack: Tom’s Substack | Tom Williams | Substack

I’ve recently written a piece for the Historical Novel Society around a book that is set in the French and Indian War. (War on the Inland Sea by Thomas Briggs.) The war is in some ways almost a mirror image of the War of 1812, which is where Burke and the War of 1812 is set. In the French and Indian War, the French, who then held the eastern part of what would later become Canada, attacked British forces holding what would later become the eastern United States. Half a century later, the forces of the United States attacked British forces in Canada.

Both were scrappy wars, with strategic movements of troops hampered by poor communications across the vast areas of land where the conflict took place. The French and Indian War ended in a decisive British victory, while the War of 1812 had no clear victor and resulted in a return to the borders that had existed before the war began.

In both wars, the armies relied on the assistance of the indigenous communities. Anybody writing about these conflicts (especially a historical novelist) runs into problems about the language they use to describe the native allies of the armies.

Nowadays, referring to the indigenous people of North America as ‘Indians’ is often regarded as offensive, which is a bit tricky when talking about a conflict usually referred to as ‘the French and Indian War’ (an odd name, given that the main combatants were the French and the British).

Ideally, I would like to call the native people the First Nations, which is the term they often used for themselves. It doesn’t really make a lot of sense, though, to people who think of ‘the Indians’ as being a single political or cultural whole, rather than recognising that there were hundreds of tribes with different political and social arrangements and very different economies. The tribes reasonably enough saw themselves as nations and, as they were there before the Europeans, ‘First Nations’ makes sense.

When I’m writing about the people that my hero deals with in Burke and the War of 1812, I try to use tribal names as much as possible, as individual identity was tied to tribal identity. Indeed, the difficulty that the First Nations had in putting aside their tribal differences and forming a unified front against the European interlopers was a major contributor to their eventual destruction.

One of the reasons why, even today, we tend to think of the various tribes as more of a unitary culture than they actually were is because the United States government deliberately treated tribal differences as relatively unimportant in their political dealings with the local population. By denying each tribe a separate political existence, they were able to negotiate with some native leaders who claimed to speak on behalf of tribes other than their own. Treaties were made giving Europeans territorial rights over land where the signatories to the treaty had no authority.

Even today, the office within the US Department of the Interior that deals with tribal governments is the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The BIA is one of the oldest federal agencies in the US, with roots tracing back to the Committee on Indian Affairs established by Congress in 1775. Unsurprisingly, especially when dealing with the US government, local people began to refer to themselves as ‘Indians’ and there are many examples of English-speaking natives using this term.

“Let the poor Indian attempt to resist the encroachment of his white neighbours…”

William Apess (Pequot) writing in English

“… their scouts … were always checked at the river Canard… by a small detachment of troops and Indians”

Teyoninhokarawen (Mohawk) writing in English

Nowadays, many people, particularly in Britain, prefer the term ‘Native American’, but I am told by Canadians that this term, too, is considered offensive and that they should be referred to as ‘indigenous people’.

What is sad is that while we argue about what the original inhabitants of America should be called, it is all-too-easy to forget about their world. A very long time ago, I travelled to America as a student and visited the Smithsonian. Nowadays, the Smithsonian has a Museum of the American Indian (not, in view of what I’ve just been saying, the most sensitive name) which must be worth seeing. When I went, hidden away in a basement, there was a large room, perhaps two, with some mannequins wearing native dress and a few artefacts. That, as far as I can remember, was it. I had sought the exhibition out specially, because I had hoped to learn about a culture not well presented in the UK. I was, to put it mildly, disappointed. Last year, I visited the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, where the representation of North American native people was even worse.

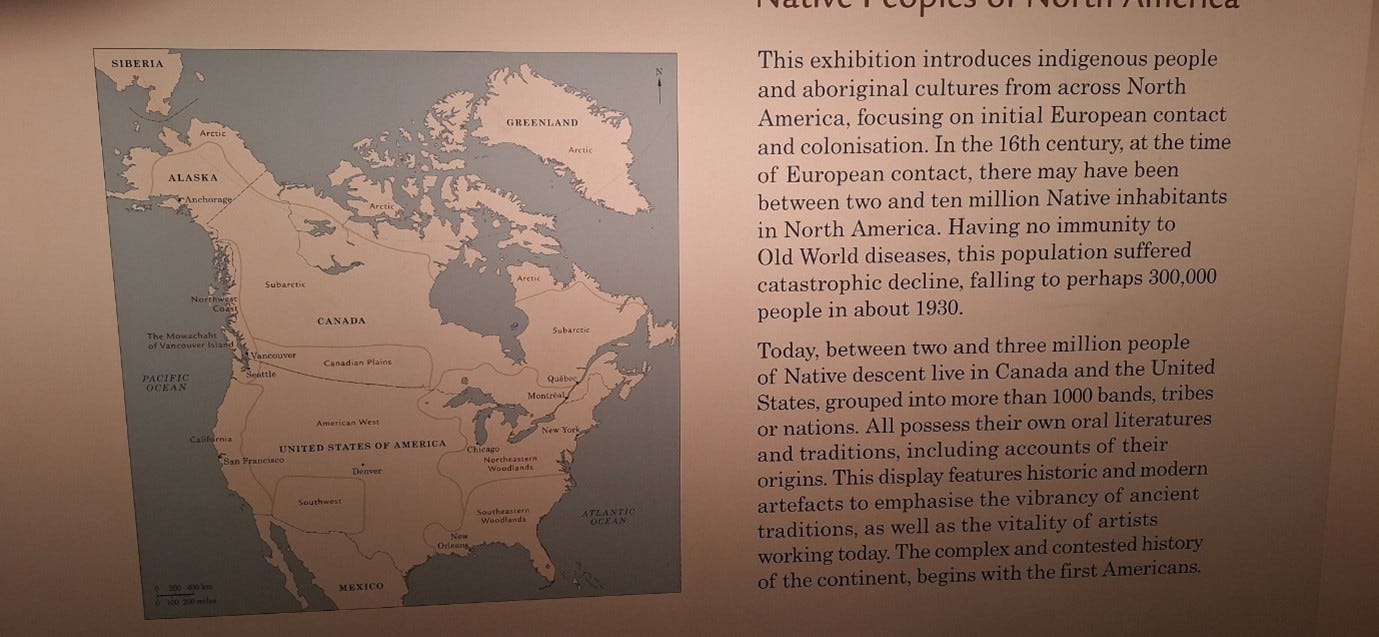

Knowing I was going to write this, I went to the British Museum to see what they had to offer. The exhibition, in a single large room, does at least confront the issue of the near annihilation of the indigenous people of North America, as you can see in the introduction shown below:

Even so, the material available is sparse. The photograph below shows everything from the display on the tribes of the Northeastern woodlands.

There were dozens of tribes in this area, which included three distinct language groups: Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Siouan. The tribes included the Shawnee, who feature prominently in Burke and the War of 1812 and whose leaders included Tecumseh, whose powder horn was shown in my post about the National Army Museum. So much culture reduced to one display case – and several of the items shown, like the pipe tomahawks, were made by Europeans as gifts to native allies or, like the box at the front right of the picture, were made by locals to sell to Europeans.

After the War of 1812, the British tried to negotiate some protection for their native allies into the peace treaty. The US promised some rights to the tribes that remained south of the border, but it was obvious to everybody that the British would not reopen hostilities simply to protect the native people. Deprived of the opportunity to expand northwards into Canada, the United States pursued its movement west with renewed vigour and acted ruthlessly against any native tribes that got in the way. In 1800 the Native American population of the coterminous United States was estimated at 600,000. By the decade 1890-1900 it was down to around 237,000.

Admitting to the mass slaughter of the indigenous peoples is probably more important than squabbles over the name we give to the survivors.

References/Further Reading

Benn C (2014) Native Memoirs from the War of 1812 John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore

Benn C (ed) (2019) A Mohawk Memoir from the War of 1812. John Norton – Teyoninhokarawen University of Toronto Press

Charles River Editors (2013) The Shawnee

Hacker DJ & Haines MR (2005) American Indian Mortality in the Late Nineteenth Century: the Impact of Federal Assimilation Policies on a Vulnerable Population. Annales de démographie historique, no 110(2), 17-29. https://doi.org/10.3917/adh.110.0017

BURKE AND THE WAR OF 1812

Burke and the War of 1812 is the latest of the series of books about James Burke, a real-life spy for the British, though most of his adventures in my books are made up. I sent him to North America because someone who enjoys the books kept on telling me what a great background the War of 1812 would provide and he was right.

James Burke (a real person, though not someone who visited North America, as far as I know) was a British spy. Back then, though, spies were expected to be diplomats (and many diplomats were spies) and Burke represented Britain in high-level negotiations, notably with the Spanish court. In this book, he is negotiating with the Shawnee leaders to make an alliance with Britain. The book is fiction, but the alliance is fact.