Search ‘1812’ on your favourite social media platform and you’ll get a surprising number of hits for a war from 213 years ago. Until a few weeks back, I doubt one person in a thousand could tell you anything about the war if they lived in either Britain or America. Rather more knew about it in Canada.

Why the sudden interest?

In a recent speech at Mar-a-Lago, Donald Trump threatened military force to take control of Greenland and the Panama canal. He also expressed enthusiasm for the idea of making Canada the 51st state. When asked if he might consider military force against the Canadians, he replied that he would not use troops but, rather, “economic force”. Doubtless the reassurance that Canada would not face American tanks rolling across the border will have come as a relief to the folks living north of the 45th parallel but the threat of economic force is still a belligerent threat. Many Canadians view Trump’s speech as a preparation for a hostile annexation of their country. This has reminded people that the USA has history in this regard. In 1812, American troops invaded Canada with the intention of seizing the territory from the control of the British and allowing the growing United States to expand northwards.

What AI imagines Trump might have looked like leading his forces in 1812

The War of 1812 was a real war but, in world affairs, rather overshadowed by events in Europe, where the continent was engaged in a brutal conflict with Napoleon. In fact, if you ask any European to tell you about military conflict in 1812, their most likely response (after ‘I don’t know anything about history’) will mention Napoleon’s march on Moscow, if only because Tchaikovsky wrote his famous 1812 Overture about it.

With the British army and navy having other things to do, there were few British troops available to fight in North America. The war was therefore fought between US troops and state militias on one side and a small British force, reinforced by Canadian militia. Both sides also made tactical alliances with Native American tribes, although the native forces were generally more sympathetic to the British, who some of them considered might offer protection against US expansion into their territories. The Americans and British also fought on the high seas with ships of both nations duelling it out in what was effectively a separate conflict.

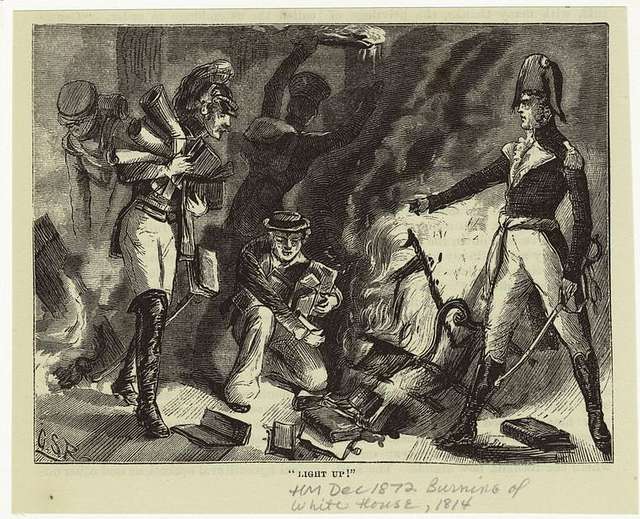

The result was, perhaps inevitably, a scrappy little war which dragged on for almost two years. With such a long border and few settlements within striking distance, the war degenerated into little more than a series of raids. The Americans would burn a village in Canada; the Canadians would burn a slightly bigger village in the United States; the Americans would burn a town in Canada and so it went on until, in 1814, the British eventually burned down the White House.

For Canadians, the war was a serious affair. Thousands were killed in battle or died of disease during the war. Canadians saw it as, in the literal sense of the word, an existentialist contest. Defeat would have meant the end of their country. At the time, Canada was British colony. Although the Canadians relied on the British Army for defence in 1812, many historians consider that driving the Americans out of their country was a significant point in their development as a nation.

For Americans, the War of 1812 became part of their country’s foundation myth. It was when the young country came of age, taking on the mighty British Empire and fighting them to a standstill. As with most myths, the historical facts of the war are often subverted to serve the interests of the myth makers. In reality, the war was an inconclusive affair. When Napoleon was exiled to Elba in 1814, the Americans realised that Britain would soon turn its full naval might against them. British reinforcements were already on their way to Canada and America was anxious to end the war before they faced almost certain defeat.

The resulting peace settlement restored the situation that had existed before the war started. The pre-war borders were reinstated. The lives lost had been sacrificed for nothing. In the end, the only real losers were the native Americans. Britain made a token effort to protect its tribal allies in the peace treaty that ended the conflict, but both sides knew that the British would not go to war to protect the indigenous people. Deprived of the opportunity to expand northwards, the United States pursued its movement west with renewed vigour and acted ruthlessly against any native tribes that got in the way. In 1800 the Native American population of what was to become the United States was estimated at 600,000. By the decade 1890-1900 it was down to around 237,000.

Until now, most people seemed happy to let the events of 1812 be forgotten. In the last few weeks, they suddenly seem relevant again. Canadians, at least, are remembering the war. They’re not very happy about what happened. Perhaps the rest of us might try to recall it and avoid another messy (but hopefully bloodless) unnecessary conflict.

Burke and the War of 1812

It’s not often that my books about the adventures of the British spy, James Burke, are suddenly caught up in the affairs of the modern world. Burke was a real person who spied for the British during the Napoleonic Wars. Although my first Burke adventure, Burke in the Land of Silver, is closely based on truth, his subsequent adventures are largely fictional. There is no evidence that he ever operated in North America, but he moved around a lot and may well have been involved in events there. At the urging of fans who enjoy reading about the War of 1812, I have written a story featuring native Americans, the Washington of the time, the Ohio militia, the siege of Detroit, and the betrayals and double-dealings that are part of Burke’s stock in trade. It’s all fun and games until somebody loses an eye, as my mother used to say, or, in this case until a farcical series of political misjudgements creates a bloody conflict that brought no good to anyone. As I said, “Suddenly caught up in the affairs of the modern world.”

Burke in the Land of Silver, is currently out with beta readers. (Let me know if that’s something you would be interested in.) Assuming they don’t find too many mistakes, it should be published early this Spring.

Picture Credits

Featured image shows the British burning Washington from Paul M. Rapin de Thoyras’ book, The History of England, from the Earliest Periods, Volume 1 (1816). Source: Library of Congress

Other pictures:

Pencil drawing depicting soldiers starting the fire in the White House is from the New York Public Library

The Battle of Queenston Heights, 13 October 1812. Library and Archives Canada, 2895485