Tyntesfield: made for photographing

Last week I spent an afternoon at Tyntesfield. It’s a National Trust property near Bath.

It was bought in 1844, by William Gibbs, a merchant who had made a vast fortune out of guano. The idea of using bird droppings for fertiliser was new at the time. It revolutionised Victorian agriculture and made Mr Gibbs one of the richest man in England. In 1863 he made the first of several significant remodellings of the house. A high church Anglican, he believed that building in gothic style evoking the English Church of the Middle Ages was an act of religious observation rather than just architectural extravagance. In this he followed the example of the Catholic architect, Pugin.

The architecture was not only designed to reflect High Anglican religious principles but incorporated space devoted to worship. An oratory, with stained glass windows, allowed William Gibbs to gather his family and all the servants to pray together morning and evening.

As William approached the end of his life, he commissioned his own chapel. This was no small private chapel (that was the oratory) but a church larger and more splendid than many parish churches. Indeed, the local vicar, nervous of losing his flock to his elaborate neighbour, petitioned the Bishop to deny consecration to the building, so it could be used only by the family. As this included servants, guests and estate workers, there must have been an acceptable congregation. Services were conducted by the family’s own chaplain, who had a specially built house in the grounds.

Building of the chapel started in 1873 and was completed in 1875 , the year of William Gibbs’ death. It is fair to say that he saw the building of this remarkable chapel as the apotheosis of his life — the crowning glory of Tyntesfield.

Victorian Gothic was dismissed as a ridiculous affectation for much of the 20th century, but it is beginning to come back into fashion. Nowadays, though, we see the religious references in the architecture (if we see them at all) as rather absurd. My first reaction on seeing Tyntesfield (a reaction I suspect I share with many of its visitors) is that it is gloriously, wonderfully mad. It is, though, quite beautiful and made for taking pictures of.

Looking through the photos I took, it is obvious that I did not take nearly enough. I must go back. But here, to be getting on with, are some of my pictures from the end of April. (All of these are exteriors. Inside is so vast and so mad that it defeated me, but I will try again on another visit.)

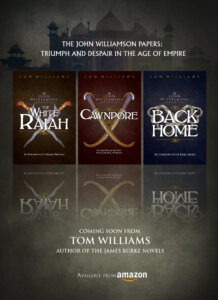

The Williamson Papers

Someone asked if this was a research trip and I said no, it had been entirely for pleasure. But it does relate to my books: not the James Burke series, which are firmly set in what historians call the long 18th century, but the Williamson Papers. My trilogy about the adventures of John Williamson, first in Borneo (The White Rajah) and then India (Cawnpore) before he returns to London (Back Home) is set around the time that Tyntesfield was being built. The money for Tyntesfield came from international trade. John Williamson is in Borneo and India because Britain trades with these places and alongside the trade comes colonial rule with all the problems, practical and moral, that that brings. Williamson returns to London where he discovers that the vast wealth that created Tyntesfield does not reach everywhere and that the poor of London are as exploited and repressed as the inhabitants of the colonies.

The Williamson Papers are not a revisionist history of colonialism. They are a first person account of Williamson’s experience and, while he is unhappy with some of the things he saw, he basically supports his country and sees a lot of good in what it does. The stories are full of excitement and incident (closely based on fact) but they should also make you question both what is now called the Empire Project and some of the fashionable revisionism which unthinkingly condemns everything that the Victorians did overseas. Unsurprisingly, I suppose, John Williamson has never had the popularity of James Burke (partly because there are only three books) but I think this is sad. I’m proud of John Williamson and he has had lovely reviews. Why don’t you make an author very happy and give them a try?