The Hundred Days

Fans of Napoleonic history (and my blog readership statistics show that there are a lot of you out there) will be very familiar with the term “The Hundred Days”. But what does it actually mean, and what did Napoleon achieve during these hundred days?

It’s an odd idea, really. In the same way as presidents and prime ministers are increasingly rated at the end of their first hundred days in power, so Napoleon’s return to France is also talked about in terms of this magic number. The ‘Hundred Days’ are regarded as starting on Napoleon’s return to Paris on 20 March, 1815 and ending with the restoration of King Louis on 8 July. Constitutionally, it’s important, because it marks the period while France was, yet again, without a king, though if you count it up it adds to 110 days. In reality, though, it’s a fairly arbitrary slice of the calendar. It doesn’t mark the period of Napoleon’s ascendancy. The failure of Louis’ men to stop Napoleon on his march north marked the end of any real power for the king, and Waterloo, though not technically the end of Napoleon’s rule, was the end of his control of France.

For students of Napoleon’s life, though, the Hundred Days are interesting because they showed the way that Napoleon had to adapt his once absolute rule to take account of the changed circumstances in which he found himself.

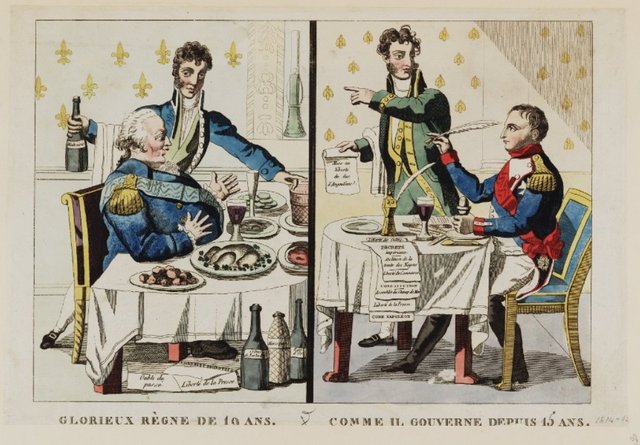

Napoleon (right) was often compared favourably with the obese King Louis (left)

Napoleon (right) was often compared favourably with the obese King Louis (left)

Despite the astonishing success of his march from the south coast to Paris, France was far from united in supporting his return. The somewhat meandering route that he took carefully avoided those areas – especially in the south and west of the country – where the population remained loyal to Louis. The king had been seen as weak and ineffective and some of the measures he’d taken to restore aristocratic privilege had caused resentment amongst the people, but this did not mean that they were necessarily going to support Napoleon. The French army had relied on conscription and hundreds of thousands of young Frenchman had been taken from their homes and families and led to their deaths, especially during the Russian campaign. This alone meant that many people were unhappy to see the Emperor back in charge.

Army reform

Professional soldiers (as opposed to conscripts) were the backbone of Napoleon’s support. He had led them, they believed, to victory (the dead of the Russia campaign were, after all, not there to argue) and he could restore French glory again.

Napoleon was well aware of the importance of the army and took care to keep the favour of the soldiery. He reinstituted the Legion of Honour and frequently inspected troops at the Tuileries, taking the opportunity to speak to the men and ensure their loyalty. At the same time, he instituted military reforms, for he recognised that he would need active military support to put down revolt at home and to protect himself against enemies abroad.

Louis XVIII had left him with few resources. The Chamber of Representatives refused to allow him to reintroduce conscription, but he was able to recall those conscripted in 1814. Officers who had served under him in the past had been stood down on half pay under Louis and they flocked to return. National Guardsmen, who were not technically available for regular military service, were swallowed up. Estimates of how many troops were recruited during the Hundred Days are unreliable. Chesney, whose Waterloo Lectures are widely regarded as an important source, considers that some of the very high estimates given are essentially propaganda by partisan Bonapartists and that, for example, they include many men who were in no fit state to be deployed. He considered that by the beginning of June Napoleon could deploy fewer than 200,000 men – a significant achievement but much less than the 560,000 that Napoleon claimed.

Liberal Reform

An Englishwoman, Helen Maria Williams, living in Paris at the time described how Napoleon had to adapt to the new situation. Her account is partisan, but accurate.

Bonaparte, conscious that his enchanter’s rod was now broken, that he was no longer believed to be invincible … had recourse to new arts. He deemed it necessary to propose a voluntary decent from the height of his ancient dictatorship, and to declare himself the patron and popular chieftain of a free government.

Bonaparte decided that his new rule would be based on a more liberal constitution that would, amongst other things, guarantee press and religious freedom and allow the possibility of an extension of the franchise. Other liberal measures were to be implemented immediately (for example, slavery was abolished on 29 March) but the Constitution was to be put to the people of France in a plebiscite.

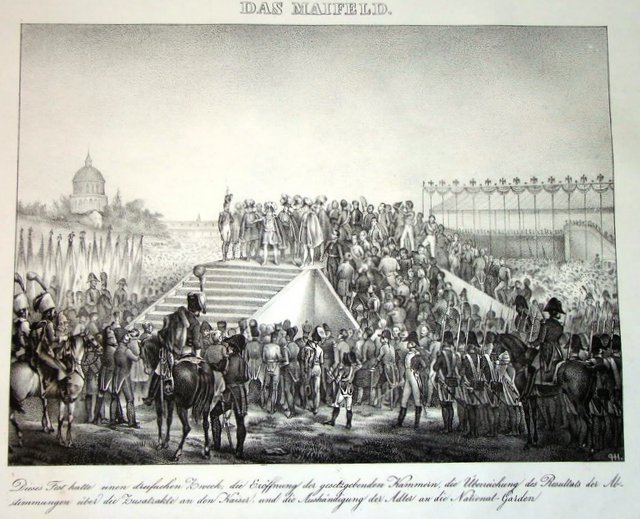

Voting was organised throughout the areas of France where Bonaparte exercised control. The plan was that representatives would travel from all over France to Paris where twenty or thirty thousand would meet at a great festival to be held in May. This “Field of May” was supposed to reflect a feudal assembly of ancient French history, where the monarch met with representatives of the nobility and the church, which was as close to a parliament as would have been known in those days. No such assemblies, though, had been held for a thousand years. Essentially, Napoleon (as he had often done in the past) was inventing a ritual to legitimise his status.

There were obvious dangers in having so many “electors” in Paris at a time when much of the country was still in turmoil. Measures were therefore taken to reduce the number who might turn up. They were to receive no money toward travelling expenses or accommodation. It was explained that when they did arrive there was to be no discussion of the new constitution but their role would be limited to verifying the registers and counting the votes.

Even with the best will in the world, the circumstances prevailing at the time would have made a plebiscite difficult. As it was, the electoral registers were drawn up locally and included only “active citizens” the definition of which was largely down to the officials. Obviously, prior to the election, Bonaparte expelled from office all those officials who were known to be favourable to the Bourbon regime. It probably goes without saying that it was not a secret ballot.

By now, Bonaparte felt that he needed the support of the people. He had been used to ruling autocratically, but now he found that the ministers he appointed would argue with him, insisting that their views be taken into account. The Chamber of Representatives (one of his liberal reforms, which he was probably already regretting) even elected a president who was known to oppose him.

In the end only 1,532,527 people voted in the plebiscite, about a fifth of those eligible, and far fewer than in plebiscites organised under the Republic, but Napoleon claimed he had the majority he needed and was, once again, the legitimate Emperor of France.

The Field of May

No one was quite sure what the ‘Champ de Mai’ would entail. The feudal ceremony was lost in the mists of history, but Parisians were promised a spectacle.

“What is the Field of May?” exclaimed the Parisians; at once something antique, and something new; when much was to be done for their liberties, and, what was not indifferent, an unknown ceremonial would be performed for their amusement. It may be observed, that one effect of twenty-five years’ of revolution is to have given the French such restless habits, that they require continually something new or strange to occupy their minds… All Paris flocked in multitudes to see what was to be seen at the Field of May.

Williams

The one thing that everybody seemed sure of was that the ceremony would be held in May, but repeated delays meant that it eventually took place on 1 June.

Helen Maria Williams described the scene in a letter home:

A spacious temporary amphitheatre had been erected for this purpose in the Champs de Mars, connected with the facade of the military school, and containing about fifteen thousand persons, seated, and covered by an awning; these were the electors, and the military deputations. The sloping banks which arise round the Champs de Mars, were crowded with people, and its immense plain was filled with cavalry. Here an altar was placed, opposite the throne, which was erected within the amphitheatre.

Napoleon arrived at ceremony dressed in Roman costume. The Mass was celebrated at the altar and then came speeches and a declaration that the new constitution had been accepted by “an almost unanimity of votes”. Then came a military parade of nearly 50,000 troops.

The spectacle was magnificent… The inspiring sounds of music, the blaze of military decoration, the glittering of innumerable arms, the countless concourse of spectators, their prolonged vociferations, the occasion, the man, the mighty events that hung in suspense, all concurred to excite feelings and reflections which only such a scene could have produced.

William Mudford

Two weeks later, Napoleon was to lead these troops north into Belgium and the start of the road to Waterloo.

References

Chesney, Charles Cornwallis (1868). Waterloo Lectures: a study of the Campaign of 1815.

Mudford, William (1817) An Historical Account of the Battle of Waterloo

Williams, Helen Maria (1815) A narrative of the events which have taken place in France : from the landing of Napoleon Bonaparte, on the 1st of March, 1815, till the restoration of Louis XVIII : with an account of the present state of society and public opinion

Picture of ‘Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of France’ is a British satirical picture published in London in 1815 and held in the Bodleian library, Oxford.

Cartoon of Louis and Napoleon is an anonymous print from 1797 held in the Bodleian library, Oxford.