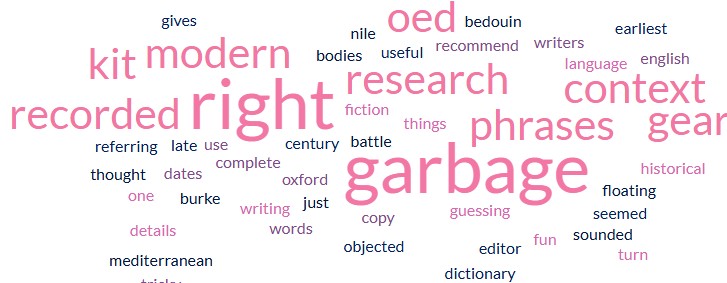

One of the fun things about writing historical fiction is the details of language that turn up. Guessing the dates that words or phrases were in use is tricky. I recommend that historical writers get a copy of the Complete Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which gives the earliest recorded use of words in their context. It was very useful when an editor objected to ‘garbage’ in the late 18th century because it seemed too modern. I was referring to bodies after the Battle of the Nile floating ‘like garbage’ in the Mediterranean (in Burke and the Bedouin). I had just thought it sounded right, but I had to check. It turns out that the word was originally used of offal and waste thrown out by butchers, so garbage was exactly the correct word – though it was mainly a happy guess.

This comes to mind because I was recently writing about the early 19th century and I referred to soldiers’ gear, which a reader said they thought was too modern. I had the feeling I had heard of ‘gear’ being used right back to knights in armour and it turns out I was right. The OED gives me ‘On ich wulle mid mine gære’ from 1305 when it often referred to ‘warlike accoutrements’. I thought the modern equivalent would be ‘kit’ but here I was mistaken in the other direction. The word was recorded, again in a military context, as early as 1785: ‘The kit is likewise the whole of a soldier’s necessaries, the contents of his knapsack.’

Phrases bring problems too and the OED won’t help here. I remember reading that an author had been criticised for referring to people in the early 20th century as ‘hanging out’ with each other, but research revealed that this was definitely a term used at the time.

It’s because of things like this that the simplest paragraph in a historical novel can lead to ridiculous amounts of research. I’m not sure that readers really appreciate it, but if you don’t like checking that sort of thing, then writing historical novels is probably not for you.