Edge of the World becomes available in the UK on Monday, but you’ve been able to watch it in the USA since 4 June and, thanks to the nice people at Signature Entertainment, I’ve seen a copy.

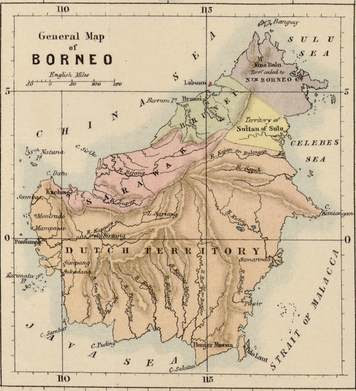

Edge of the World tells the story of how James Brooke travelled to Borneo, got caught up in a civil war there, and ended up the ruler of his own country of Sarawak. He starts out wanting only to do his best for the native Dyaks of Sarawak but, when they are threatened by marauding pirates he finally takes up the sword (all too literally) to protect his rule. “And so,” Brooke says in a voice-over, “I am ruined – but free.”

The film is much closer than I expected to the story I tell of James Brooke in The White Rajah. It shows how Brooke starts out with a naïve wonder at the beauty of Sarawak and at the pleasure that he gets from being a wise and benevolent ruler and ends up leading his people in the bloody massacre of his enemies. He can no longer be the ‘civilised’ white man bringing his European values to the benighted natives: “To rule the jungle,” he eventually comes to realise, “I must love the jungle. All of it – the beauty and the blood.”

For me, this is the key to understanding the basic problem of colonialism: the European powers found themselves ruling people they did not understand. Brooke was successful because he did understand – but this meant that he committed the dreadful sin (in European eyes) of ‘going native’. The film does catch the concern of the British about this when a delegation from England visits him and is appalled by his tolerance of “your niggers” and refuses to help him in what they see as a battle between two tribes in which England has no interest.

The response of the British to Brooke’s request for naval help is typical of the way that the film treats the historical record. The relationship between Brooke and Britain was a source of irritation to the British and was ultimately the reason for the public inquiry held in Singapore. But this was after the British had intervened with a small fleet (including the steamship which is talked about in the film) and assisted Brooke in the massacre (which was much bigger than depicted in the movie). The film tells a good story and uses real incidents from Brooke’s life, but the incidents are often changed or moved around in a way that cheerfully disregards the historical record. Even so, it was much more true to the history than I ever expected.

I particularly enjoyed meeting Budrudeen and Makota, depicted (as in my book) as the good guy and the bad guy respectively. The conflict between the two drives much of the plot, though you’ll have to watch carefully because the politics is easily lost in the lavish spectacle. I liked the clear implication that Budrudeen’s feelings for Brooke went beyond affection. Sadly, even in 2021 Hollywood can’t bring itself to admit that Brooke may have reciprocated those feelings.

This brings us neatly to the biggest liberty that the film takes in introducing the love interest that Lady Sylvia Brooke vetoed back in the 1930s (see last week’s blog). This doesn’t entirely work, not only because (despite some local legends) it almost certainly didn’t happen, but because the script suddenly inserts this woman (only ever referred to as ‘Fatima’) with no clear explanation of how she turns up in Brooke’s life. Atiqah Hasholan makes a good job of bringing the character to life, but she always appears as a sort of disposable bolt-on. Indeed, at one critical moment she leaves, vanishing from the story until (at another critical moment) she reappears. Like all of the film, it’s visually brilliant and it definitely packs an emotional punch, but we have left history and emotional logic far behind.

Because it’s 2021, the film also plays up the ‘the Empire was evil’ line. Brooke’s cousin (a real person called Arthur Crookshank) is presented as one of the members of the original expedition (which he wasn’t) and he stalks through the movie wearing a red coat and waving a pistol and generally representing British imperialism at its jingoistic, ignorant worst. Imperialism was, of course, often jingoistic and ignorant (though less so in Sarawak than in most places) but Crookshank’s ghost deserves better than to see its character represented as a cartoon buffoon. The Empire was seeking to expand in the Far East, but the manoeuvring over Sarawak was an exercise of inquiries and memos and diplomatic arguments that went on for years. It did, indeed, end with Sarawak becoming yet another Crown Colony, but that was in 1946 and would make a much longer (and rather dull) film.

Enough analysis of the history: is it worth watching? Yes, it is. It has an uneven start (sticking with the historical record would have made it stronger, but the budget only extended to ‘first contact’ being with a bunch of head-hunters in the jungle). Once it gets going, though, the issues of colonialism and Brooke’s feelings about Sarawak begin to drive the plot and it picks up pace with a clearer sense of direction.

The climactic battle suffers (like most climactic battles) from budget issues. What should have been a huge attack by British Marines and Brooke’s Dyaks, covered by the new-fangled Congreve rockets, which destroyed a substantial village and killed hundreds of people, becomes a bit of a squabble on a beach. No matter: the cinematography is brilliant, the actors emote with a script that gives plenty of opportunity for them to show passion and triumph and despair, the plot (despite its confusing moments) offers excitement and intrigue enough to keep you watching.

If, when it’s over, you feel that you would like an alternative approach to the same events (still fictionalised but rather closer to the historical record) The White Rajah is an almost perfect companion piece to the film.

Buy links

You can see the film trailer here: https://youtu.be/YQ8mrNmTPjY

You can buy the film here:

iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/gb/movie/edge-of-the-world/id1568753299

Amazon DVD: https://amz.run/4aGX

You can buy my book (paperback or Kindle) here: https://mybook.to/WhiteRajah