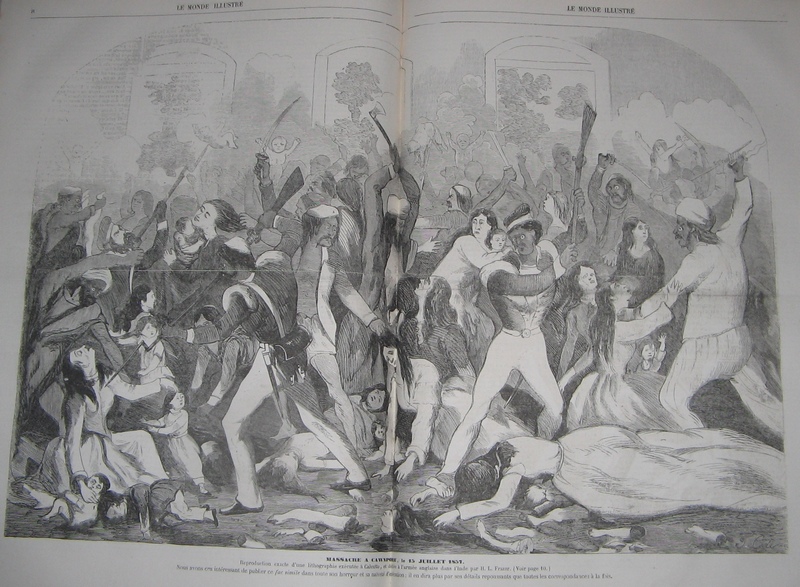

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about Nana Sahib, “the demon of Cawnpore”. I suggested there that the rights and wrongs of his behaviour (and that of the British) were not as straightforward as they are often presented. Even so, when Heather Campbell of The Maiden’s Court invited me to write the story from Nana Sahib’s point of view, it was a serious challenge. After all, how do you set about justifying a war crime?

In the end, I was pleased with what I wrote and I thought I’d like to share it here. I know that a lot of people who read this blog are interested in writing and I do recommend things like this as useful exercises. And for those who don’t write, I hope you can just enjoy it as a different way of looking at an infamous bit of Indian history.

Nana Sahib’s story

My father was the Peshwa of the Maratha Empire. He was a mighty lord who rose against the British who had come into his country and despoiled it. He fought valiantly against the invaders, but he was defeated and exiled from his own country to the miserable little village of Bithur, not far from Cawnpore. The British allowed him to retain his title and a small pension and he made his peace with them and lived alongside his enemy until he died in 1851.

I was an adopted son – a common practice in my country when a great lord has no sons of his own – but the British refused to recognise me as Peshwa and no longer paid the pension that they had paid to my father.

Despite the loss of my lands, my title and my pension, I tried to be a good friend to the British. They had ruled in India now for a hundred years and many Indians had accommodated to them. But their rule was becoming more harsh. Where once they had made honourable peace with men like my father, now they seized their lands, ignored their titles, and denied them the respect they were due in their own country. They began to send Christian missionaries who tried to tempt my people from their faith. They told us we must abandon our old customs.

Those Indians who served in their armies (for there is no disgrace in serving the army of any lord once he has proved himself a power in the land) were not accorded the respect they had been. Their officers, who had once loved this country, were replaced by arrogant fools who did not understand our ways. There were rumours that they might be sent overseas, where they would lose their caste. Then there was the terrible business of the new cartridges. The cartridges were greased with the fat of cattle and with the fat of pigs. This was an insult to all the Hindus in the Army and to their brothers who were Moslems.

Finally, the people of India rose up against these injustices. I was not sure what to do. I had been friends with the British and I hoped that things could be settled without violence, but it was soon apparent that there must be a war and that the British would finally be driven from our country. My people looked to me, for they still called me “Peshwa” and acknowledged me as their leader. Now that it had come to war, it was my duty to lead my people against the British in Cawnpore.

The British fought bravely: I will give them that. Hundreds of my troops died as we attacked their fort again and again. In the end, I agreed to lift the siege if they would go. They said they would and asked for boats to sail down the Ganges to rejoin their people. But this had to be a trick. The British were being defeated everywhere. Where could they hope to go? No, once they were on the boats they could set up a fort somewhere else and attack us from there. My generals told me I would be stupid to let this happen.

What was I to do? They had surrendered, but there was nowhere they could go. We had an army in our midst that could turn on us at any time. The British, we Indians had learned over the past hundred years, were liars. They had promised my father he could keep his title and then took it from me because I was adopted: a cheap trick. They had stolen the Kingdom of Oudh on the same pretence – that the new King was adopted, and therefore could not inherit. We could not trust them.

My general, Tatya Tope, told me what to do. He arranged to have artillery hidden across the river from the boats and for his men to conceal themselves along the banks. When the British came to the boats, we opened fire. They still had their muskets. It was war: these things happen. We tried not to kill the women and children, but we took them captive and kept them safe.

Then news came that a British force was on its way to relieve the siege. Everybody was terrified. The British were killing people who they thought might have ever harmed any of their troops and they would kill us all if they heard what had happened by the river. It was essential that any of the British who might speak against my sad, but necessary, actions should be silenced. I had no choice: the women and children would speak against me. They had to die. So many Indians had died under British rule and the British always said that sometimes these things were necessary or that sometimes these things just happened. But would they have happened if the British had not stolen our country? Had we asked these women and children to come and live amongst us, ordering their Indian servants to do this and to do that as if they were slaves? Bringing their foreign ways, their terrible food, their arrogance and their ignorance? They looked down on us as savages and sneered at our ways. Well, they’re not sneering now.

The British beat us in 1857. I was driven into exile and watched as the white men tightened their grip on my country. But I know that our time will come. It is not right that the Indians should live under the rule of the British and one day we will rise up and we will defeat them and I will not be hated by the rulers of India, but loved by them as one of those who showed the way to regaining our own country.

Cawnpore

The story of Cawnpore and the clash of cultures that led to the massacre is the subject of my book, Cawnpore. The narrator is English, but in love with an Indian. Caught between the two camps, he sees the tragedy developing around him, but is powerless to stop it. Can he survive the massacre and, if he does, can he save anyone else from the horror?

Cawnpore is the second of my books about John Williamson but it stands alone. Of the three, it is my personal favourite.

Cawnpore is available on Kindle and in paperback. It has had some lovely reviews.

“All that historical fiction should be: absorbing, believable and educational.” – Terry Tyler in Terry Tyler Book Reviews

“For anyone who has a love for this period, Cawnpore is probably one for you.” Historical Novel Society

If you haven’t already, I do hope you will buy it soon.