While I was writing here about Waterloo, I had a suggestion that I wasn’t paying enough attention to the human cost of the battle. I promised I would come to this and we’ve not talked about Waterloo for a while, so this week might be a good time to come back to the battle and. more particularly, its aftermath.

Waterloo was far from the bloodiest battle of the Napoleonic wars (that dubious distinction belongs to Borodino). However, the number of dead in such a small field was horrific. An idea of what it was like can be gathered from this account by an anonymous private soldier:

In the first place, the ground, whithersoever we went, was strewed with the wreck of the battle. Arms of every kind, cuirasses, muskets, cannon, tumbrils, and drums, which seemed innumerable, cumbered the very face of the earth. Intermingled with these were the carcasses of the slain, not lying about in groups of four or six, but so wedged together that we found it impossible in many instances to avoid trampling them, where they lay, under our horses’ hoofs; then, again, the knapsacks, either cast loose or still adhering to their owners, were countless. I confess that we opened many of these, hoping to find in them money or other articles of value, but not one which I at least examined contained more than the coarse shirts and shoes that had belonged to their dead owners, with here and there a little package of tobacco and a bag of salt; and, which was worst of all, when we dismounted to institute this search, our spurs forever caught in the garments of the slain, and more than once we tripped up and fell over them. It was indeed a ghastly spectacle, which the feeble light of a young moon rendered, if possible, more hideous than it would have been if looked upon under the full glory of a meridian sun; for there is something frightful in the association of darkness with the dwelling of the dead; and here the dead lay so thick and so crowded together, that by and by it seemed to me as if we alone had survived to make mention of their destiny.[1]

Print of William Frye’s painting of Waterloo after the battle

Print of William Frye’s painting of Waterloo after the battle

The French had specialised sprung ambulances to transport their wounded, but in the chaos of the French defeat their wounded were abandoned on the field. As darkness began to fall, the victorious allies began to sort the living from the dead, carrying those who could not walk in whatever carts they could find.

We found on every side poor fellows dying in every variety of wretchedness, and had repeatedly to join the strictest silence that we might hear their scarcely audible groans … Before morning we collected several wagon-loads of brave fellows, friends and foes. [2]

Whilst the Allies did attempt to remove the casualties and give them medical care, the sheer scale of the exercise meant that people lay in the open for days – by which time, of course, most of them were already dead. Only after the Allied troops had been cared for did the British turn to the French. An anonymous Staff officer who was there wrote:

I have reason to believe it was not till the fourth day after the battle that the last of the French were taken up; and it is painful to think of the suffering they endured from pain, cold, and even hunger, during so many weary days and nights, – numbers of them, doubtless perished who would have survived had they been taken care of. Neither does it appear that any food was regularly supplied to them … [3]

The British had set up a field hospital at Mont St Jean in a big farmhouse that still stands today. This is an account of the site by a sergeant of the Scots Greys:

We having arrived at the farmhouse, Mont St Jean, which is situated on the road in short distance in front of the village of the same name, entered the yard, where a most shocking spectacle presented itself. This house and yard, during the time of the battle, had been occupied by some of the British and Belgic surgeons and in it many amputations had been performed. A large dunghill in the middle of the square, was covered with dead bodies and heaps of legs and arms were scattered around! A comrades who stood near me on entering unconsciously muttered “Oh God. What a sight.” To which I made no answer, but felt as he did, for a great number lay by the sides of the house and basked in the beams of the sun who had only life’s last spark remaining and gasped for relief. [4]

The farmyard at Mount Saint Jean as it is today

The farmyard at Mount Saint Jean as it is today

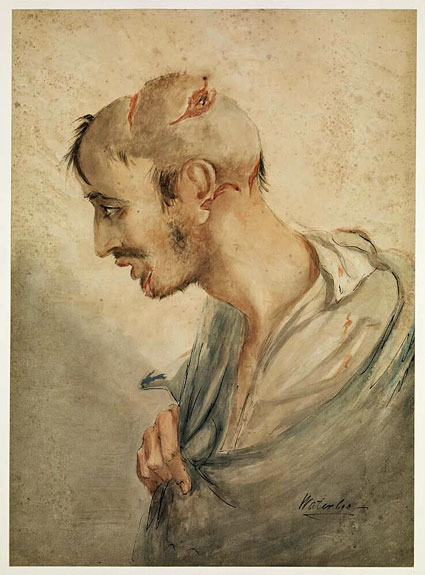

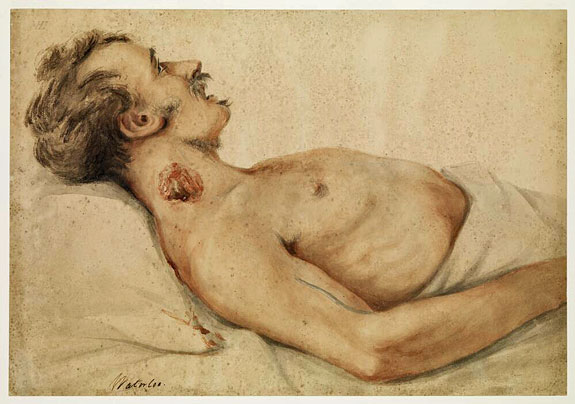

Here the surgeons had to deal with a range of injuries. The Scottish surgeon, Charles Bell, who was operating on French soldiers in the Gendarmerie Hospital, made detailed watercolour paintings of the sort of things treated at Waterloo.

Sabre wound to head. (Wellcome Library) Grapeshot wound to the neck (Wellcome Library)

Most wounds were caused by gunshot and the main concern of the surgeons was to remove the ball and ensure that the wound was left clean. Usually the ball would have carried fragments of clothing into the wound and these had to be carefully removed one by one with forceps. Remember that this would have been done while the patient was fully conscious.

A major cause of death was infection. Gangrene was a particular problem. Without antibiotics the only way to treat wounds that were liable to turn gangrenous was by amputation. Arms and legs were cut off with gay abandon. There was a pile of detached limbs in the courtyard shown in the photograph above.

I observed with some warmth of national feeling, several highlanders’ legs, still wearing the emblem of their country; Auld Scotia’s tartan hoe! As also the legs of dragoons in boots and spurs and many others which still wore a part of the garment in which they had proudly paced the causeways of their native land. [5]

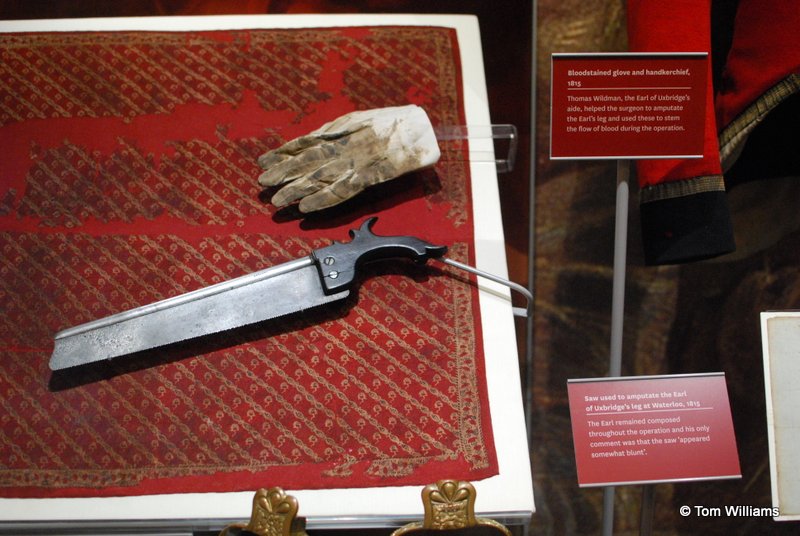

The secret of a successful amputation was that it should be done very fast. A sharp bone saw was crucial to a surgeon’s success rate. The photograph below shows the saw that was used to remove the leg of the Earl of Uxbridge, who had been hit by a cannon-ball while sitting on his horse alongside Wellington.

Bone saw displayed at National Army Museum

Bone saw displayed at National Army Museum

Surgeons had to work quickly so that their patients did not die of shock as they went through the amputations unanaesthetised. But there was another reason for speed as well. There were only 270 surgeons available to treat the wounded, and with tens of thousands of men requiring attention they had no time to spend on any but the most basic of procedures.

As the wounded were moved from the battlefield, so Brussels filled with makeshift hospitals. Soldiers who were less badly injured were cared for in the parks, because all the buildings were full, with contemporary accounts claiming that every private house had three or four wounded soldiers in it. [6] Modern authors estimate that around 62,000 Allied and French wounded flooded into Brussels, Antwerp, and other towns and cities of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. [7] The scale of the horror was such that a British tourist (himself an ex-Army man) wrote ten days after the battle:

You may form a guess of the slaughter and of the misery that the wounded must have suffered and of the many that must have perished from hunger and thirst, when I tell you that all the carriages from Bruxelles, even elegant private equipages, landaulets, barouches and berlines, have been put in requisition to remove the wounded men from the field of battle to the hospitals, and that they are yet far from being all brought in. [8]

References

- Quoted by Gleig in his Story of the battle of Waterloo p253

- Augustus Fraser: Letters of Colonel Sir Augustus Simon Frazer, K.C.B. commanding the Royal horse artillery in the army under Wellington, Written during the peninsular and Waterloo campaigns

- Recollections of Waterloo by a Staff Officer United Service Magazine 1847 PartIII p355

- Sgt William Clark, whose writings have recently been published as A Scots Grey at Waterloo edited by Gareth Glover

- Ibid

- After Waterloo – Reminiscences of European Travel 1815-1819 by W E Frye

- See, for example, Michael Crumplin and Gareth Glover (2018) Waterloo – after the glory

- Frye ibid

To be continued …

There is more about the aftermath of the battle in next week’s blog.

Wow, so much suffering. I wonder if those memories haunted the survivors for the rest of their days?

I have no idea, but I’ve had a couple of responses on Facebook from people with great great great grandfathers who lost limbs at Waterloo and whose stories have passed down the generations, so at least some ordinary soldiers survived and went on to live normal lives.

It’s been amazing to read these stories which offer a direct link to those times.